Famous Folks and Me

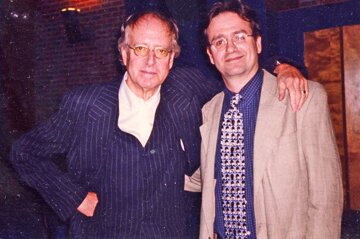

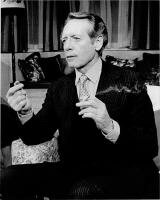

TS with  Patrick McGoohan, 1984

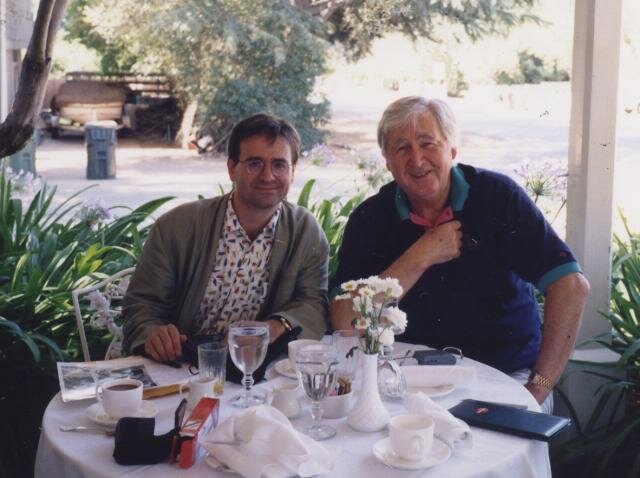

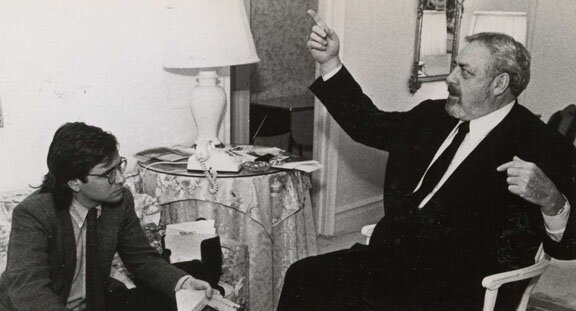

Patrick McGoohan, 1984  Raymond Burr, 1986

Raymond Burr, 1986  Michael Palin, 1987

Michael Palin, 1987  Terry Jones, 1990

Terry Jones, 1990  John Barry, 1996

John Barry, 1996  Fess Parker, 1998

Fess Parker, 1998  Lalo Schifrin, 2002

Lalo Schifrin, 2002

Charlie Chaplin

HAVE I OFFENDED YOU?

By Tom Soter

I don't remember much about my meeting with Charlie Chaplin except that he seemed to be an awfully nice guy. Here's how it happened: it was the summer of '65 and I was just eight (going on nine in October). My father had packed the family – my mom and my two brothers – off to Jamaica for a holiday. (Usually we went to Greece, although I was such a fan of TV's Daniel Boone that I once complained about going to such exotic locales insisting instead that we visit Boone's hunting ground, Kentucky. Ah! Innocent youth!) We were staying in a little bungalow on the beach and our neighbor happened to be Charlie Chaplin.

Yes, the Little Tramp himself was next door, working on the screenplay for what would be his last film, A Countess from Hong Kong(1966). My father felt very respectful of Chaplin's privacy and so, whenever the great man and his family (his wife and two young children) came out on the beach, my dad would quickly hustle us off to our bungalow, so that Charlie could be alone. After two or three days of taking these speedy exits, Chaplin sent a man over to our bungalow with a message: "Mr. Chaplin would like to know if he has done anything to offend you. You don't seem to want to share the beach with him." My father sent a message back explaining, and the next thing we knew, Chaplin had invited us over to have some tea.

He was white-haired and much heavier than the man I had seen in the movies, but he still had a twinkle in his eye and was very attentive to the children. I remember him talking with me in a quite grown-up way about my hand-drawn comics, as he quite seriously discussed plot points with me as though I were a great author and not just a nine-year-old boy.

We may have seen him once or twice after that, but the only other thing I still remember about that time was the night the resort showed a documentary on silent movie stars. I couldn't quite relate the man I had recently met with the energetic man I saw glidng effortlessly on the screen, taking pratfalls with operatic grace. It seemed like a different world. And it was – as different to me then as Jamaica in 1966 and meeting Charlie Chaplin is to me now. July 2008

Decker Departs

The e-mail was forwarded to me by my friend, Alan. He wrote me a note: "This is someone with too much time on his hands," citing the forwarded e-mail that listed STAR TREK actors, writers, and other personnel who had died in the last year. I scanned the list and was brought up short by this entry:

WILLIAM WINDOM (88); died August 16. Actor; portrayed Commodore Matt Decker in the original STAR TREK series episode "The Doomsday Machine." He is perhaps best known for his recurring role as Dr. Seth Hazlitt on the series MURDER, SHE WROTE. He is also remembered for playing Congressman Glen Morley on ABC's 1963-1966 comedy THE FARMER'S DAUGHTER and for his Emmy-winning work as star of the short-lived NBC sitcom MY WORLD AND WELCOME TO IT. He performed in several Broadway and off-Broadway plays between 1946 and 1960 and made his feature film acting debut as the prosecutor in the 1962 classic TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD. His subsequent film credits include THE AMERICANIZATION OF EMILY, HOUR OF THE GUN, BREWSTER MCCLOUD, ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET OF THE APES, SOMMERSBY, TRUE CRIME and the John Hughes comedies PLANES, TRAINS & AUTOMOBILES and SHE'S HAVING A BABY.

Windom dead! He was a familiar face in my youth as a guest star in THE FUGITIVE (he was in one of the color episodes), and was memorable as the ill-fated Commodore Decker in STAR TREK’s “The Doomsday Machine,” as the last survivor of a starship wrecked by the giant planet killer that was quite terrifying, even if it did look like a gigantic meatloaf. I’ll always remember his overwrought and emotional exchange with Capt. Kirk (William Shatner), who asks Decker: “Where’s your crew?”

“On the fourth planet.”

“There is no fourth planet.”

“Don’t you think I know that?” He then goes into an impassioned monologue about how he sent his crew to their deaths, and how powerless he was to help them.

It is an agonizing, melodramatic, moving, and hammy performance – out-Shatnering Shatner – yet it somehow works, making you feel for the man even while you appreciate the artiface. It’s the kind of work ‘60s TV actors did so well – and Windom’s death reminded me of another of his performances as a lonely disappointed man who reflects bitterly on his life in Rod Serling’s NIGHT GALLERY teleplay, “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” I haven’t seen it in 40 years, but Windom’s deft performance stays in my memory.

It also resonated with me when I actually met Windom, many years after that. I was visiting my brother in San Francisco and we happened on a comic book/film and TV convention in his neighborhood. We dropped in through an open back door and came on the familiar figure of William Windom, standing by a fold-out table displaying 8 x 10 photographs.

“Hello,” I said, slightly in awe of the Great Man, and not really knowing what to say (do you ask him, as fans do, to repeat his decades-old dialogue from STAR TREK?). My brother, Nick, chimed in, asking Windom, “What do you have here?”

“Well, for $10, I’ve got black and white photographs from STAR TREK, and for $15, I’ve got color.” I looked at the photos. They weren’t even real photos. They were Xerox copies.

It was sad, like a scene from a second-rate Arthur Miller play – or a moment from “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar.” Here was Windom, an accomplished actor, now paunchy and apparently down on his luck, reduced to hawking Xeroxes of himself. At a table next to him was Gary Lockwood, who had also appeared in STAR TREK and in 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY as the astronaut who goes floating off into space. He was apparently tipsy.

Windom had more dignity than that. “You’ve got to get the color shot,” said Nick.

I paid the $15. “Would you like me to autograph it?” asked Windom. I nodded my head.

He wrote, “Thanks, Tom! Wm Windom, ‘Cmdr Decker.’”

February 2, 2013

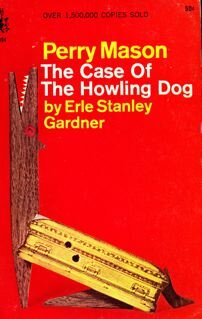

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of THE BANG-UP BIRTHDAY

By TOM SOTER

By TOM SOTER

Three years after I met Charlie Chaplin, I had a brief correspondence with someone who was much more significant to me at the time: Erle Stanley Gardner.

It was July 1969, and I was 12 years old, going on 13 in just three months. As I entered my teenage years, I continued with my childhood habits: watching my favorite television programs (Daniel Boone, Ironside, Perry Mason, The Prisoner), making radio shows with my friends on reel-to-reel tape-recorders (crazy things with tiltles like Planet of the Nuns and West that Wasn't), going to the movies (James Bond was a favorite along with revivals of classics at Theater 80 St. Marks, the Thalia, and the Regency, all long-gone movie houses), and reading my favorite authors.

Reading was, like everything else I did, done obsessively: I would find an author I liked, and then read everything by him I could find. In 1966, to widen my interests away from Daniel Boone, my dad introduced me to Tarzan, and I was soon going through all 25 Tarzan novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs (titles that I could recite – rather scarily, I think now – to friends and family in chronological order), as well as his 11 Mars books, 7 Pellucidar novels, 4 Carson of Venus books, and so on through ERB's entire oeuvre. Then in 1968, I discovered Erle Stanley Gardner. I don't remember exactly how I hit upon him, except that iit must have had something to do with my watching reruns of Perry Mason on TV (it was on at 11 P.M. weeknights on Ch. 11 in New York, and I would catch it on Friday nights, which was my marathon TV-watching night, starting with Wild Wild West at 7:30 and ending with Mason at 11). Raymond Burr's lawyer-sleuth Perry Mason was a commanding figure: the lawyer who always got his quarry through relentless cross-examination of prosecution witnesses, finally obtaining a murder confession, usually on the basis of circumstantial evidence and frequently in a preliminary hearing (not even a real trial). Perry Mason had been a log-running hit, from 1957-1966, and it was the brainchild of Gardner, who, by 1969, had become the best-selling, arid most prolific American writer of the 20th century, with paperbacks selling at the rate of 20,000 a day and all-time sales, as of 1977, nearing 304 million copies in 23 languages. The lawyer-detective, who ultimately starred in 82 novels, a dozen short stories, six movies, 271 television episodes, and countless radio shows, first appeared in The Case of the Velvet Claws in 1933. It was turned down by a number of publishers before being accepted by Thayer Hobson, president of William Morrow & Co., who suggested that Gardner specialize in a series character rather than create new heroes and new locales for each adventure.

Perry Mason had been a log-running hit, from 1957-1966, and it was the brainchild of Gardner, who, by 1969, had become the best-selling, arid most prolific American writer of the 20th century, with paperbacks selling at the rate of 20,000 a day and all-time sales, as of 1977, nearing 304 million copies in 23 languages. The lawyer-detective, who ultimately starred in 82 novels, a dozen short stories, six movies, 271 television episodes, and countless radio shows, first appeared in The Case of the Velvet Claws in 1933. It was turned down by a number of publishers before being accepted by Thayer Hobson, president of William Morrow & Co., who suggested that Gardner specialize in a series character rather than create new heroes and new locales for each adventure.

I loved the Mason novels almost as much as I loved the Tarzan adventures (although there were three times as many of the former as the latter). I methodically went through the Mason stories (eventually reading 60 or so of he 82 Masons). They were crackling good whodunnits, much more involved than the TV shows but just as tightly plotted. As a stylist, Gardner was no Henry James, but he was a damn fine storyteller, keeping the pace and your interest up to the last page.

In July 1969, I was in"exile" in a house by the beach in Greece from June to September (my parents called it a vacation – one that I would welcome now – but at the time I was frustrated being separated from my friends and habits). While there, I wrote a letter to Erle Stanley Gardner, wishing him a happy birthday (it was on July 17, and he was turning 80). It was probably like no other fan letter or birthday greeting he had ever gotten. I don't remember all of it, but it essentially said, "Dear Mr. Gardner, I wanted to wish you a happy birthday. You are my second favorite author" – Burroughs was my favorite – "and I have read 43 of your Perry Mason novels, which I enjoy immensely."

Soters in Greece, 1969.

My father, in America at work (he would join us periodically in our months-long stay in Greece) sent the letter to Gardner's publisher, and when I returned to New York in September, there was a response waiting for me. It was on stationary that featured a drawing of cactuses in the desert, with letterhead that read, "Erle Stanley Gardner, Rancho Del Paisano, Temecula, California." I remember being very excited as I read,

Dear Tom,

It was very thoughtful of you to send me a birthday greeting – and doubly so for you to take time out while you are vacationing. I had a bang-up birthday and your letter certainly added to my enjoyment... Thanks a lot for remembering me, and I hope you had a wonderful vacation.

It was signed, in an almost unintelligible scrawl, "Erle Stanley Gardner."

That was the extent of my "correspondence" with the great man. Since then, I've met many other heroes of my youth, and although each encounter was exciting in its own right, none hit me in quite the same way as Gardner's letter. Its kindness overwhelms me to this day: rather than ignore a neurotic 12-year-old (after all, who tells a best-selling writer, "you are my second favorite author"?), he not only responds but treats the kid as an adult (very classy for him to thank me for taking time from my vacation to write him, reversing our importance). For a skinny pre-teenager, such respect from an adult was delightful.

Gardner died about six months later. He had millions of fans and presumably millions of mourners, but out of all of those, I remember thinking at the time, no one else had added to his enjoyment the way I had. I figured that, for at least one brief moment, I was special. And yes, Mr. Gardner, I had a wonderful vacation.

May 1, 2010

Fess Parker

MY BREAKFAST WITH FESS

By TOM SOTER

Fan meets the man: Fess Parker, with TS, 1998

It all started with a phone call. Every summer, from 1992 until 1998, I had been traveling to San Francisco to visit my older brother, Nick, and his family. Every year, before I came out, he would ask me, “What would you like to do when you come here?” And every year, invariably, I would say, “I don’t know. Hang out, relax, read.” As you can see, I wasn’t a big vacation planner. But this year, 1998, I had an idea. “Why don’t we go to the Fess Parker winery?'

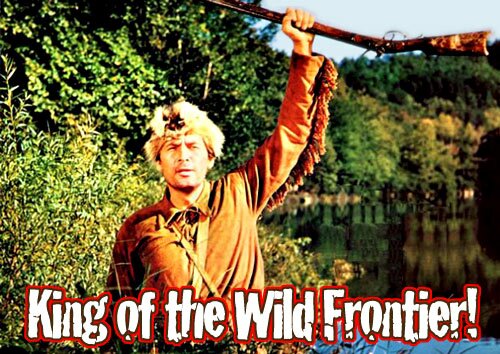

Now, Fess Parker, as baby-boomers of the 1950s know, was Davy Crockett, an American frontiersman who famously died defending Texas at the Alamo and who was immortalized in the song, “Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier.” That tune was sung in the Walt Disney mini-series (there were only five episodes), Davy Crockett.

And baby-boomers of the 1960s, like me, knew him as Daniel Boone, who may not have been king of the wild frontier but was pretty remarkable nonetheless (as his theme song explained, he had “an eye like an eagle” and he was "as tall as a mountain”). In my youth, I had been obsessed with Dan’l. (On the show, everyone called him that, except for his wife, Becky – she called him Dan – and his two friends, the Oxford-educated, part-Cherokee Indian Mingo, and the runaway slave Gabe Cooper, who both called him Daniel.) I had a hat reportedly made from a raccoon (a coonskin cap), I had a buckskin jacket with fringes, and I even owned an imitation musket (the single-shot rifle used by men like Boone). I also kept checking out my high school library’s copy of the biography Daniel Boone: The Opening of the Wilderness every week (when they retired the library card they gave it to me). And I would often go to sleep listening to audiotapes I had made of the theme song to the Daniel Boone TV series (“Daniel Boone was a man, yes a big man....”)

Daniel Boone toy fort, 1964.

Even though it was a long drive – Parker’s winery was closer to Los Angeles than San Francisco – my brother agreed to the idea of visiting the winery. But it was his wife, Dora, always practical, who came up with the killer idea: “As long as you’re there, why don’t you try and set up an interview with Parker?” As my brother added: “Yeah, as long as you’re traveling all that distance, you might as well get something besides a coonskin cap!”

As a freelance writer, I had met and interviewed many celebrities in the past, including some who were childhood icons – Patrick McGoohan, Raymond Burr – but Fess Parker was at the top of my list (perhaps sharing the space with McGoohan). I figured one of my clients (such as Entertainment Weekly or Diversion) would jump at the chance to run a piece on Parker, so I called up the winery and arranged an interview with the great man (it was surprisingly simple). The drive was uneventful. We stayed in Parker’s hotel complex (he had just bought the Grand Hotel chain) and drank his wine, which my brother, often critical of food and drink, found remarkably good. We bought some bottles of wine, calling them “bottles of Fess.” It was all delightful.

My appointment was for breakfast, the next morning. I arrived, nervous and excited, to find him sitting with an assistant, a pleasant young man, at a table on the porch. He was tall (over six feet), white-haired, and slightly jowled, but he was still recognizably the "big man with an eye like an eagle" who "rassled alligators" and wowed a nation as a overnight sensation in 1955 as "the king of the wild frontier." Not surprisingly, he eschewed buckskins – “too hot,” I thought to myself – and was dressed in a short-sleeved blue polo shirt (imprinted with the logo “Fess Parker Winery”) and slacks. He smiled that affably crooked grin that I knew so well from countless Thursday nights of Daniel Boone-watching as he stood up to shake my hand. We sat on the front porch, and as we talked, he leaned forward occasionally to make a point. He gave detailed answers on any subject he was asked about, but when he finished speaking, he came to a full stop and politely waited for the next question.

Parker as Crockett: baby boomers knew his song

Parker as Crockett: baby boomers knew his song

We initially talked a bit about the winery – he was very proud of it. How had it all started? Realizing that he was typecast as a television frontiersman, he explained, he began exploring other business frontiers. In the 1970s, he invested his money in hotels and was now running a phenomenally successful chain of Fess Parker Hotels. Then, in 1987, he purchased 714 acres of ranch land in Los Olivos, California, which became the home of his vineyards, winery, and families (he had a son, daughter, and grandchildren).

The family enterprise released its first wine in 1989. In 1998, the Parkers had 25 employees and 65 acres of vineyards plus another 85 acres in Santa Maria, California, with 25 more acres to be planted that year. The Parkers put a lot of effort into creating a destination where people would come and linger. The 9,600-square foot winery building, which was completed in 1994 in a handsome English colonial style, had a rambling veranda that was immensely popular with visitors. Parker chose the architectural design himself after seeing similar architecture in Australia on a 1985 visit to represent the president of the United States at the Coral Sea Celebration. The winery wasn’t an instant success, recalled Parker, who acknowledged that he had to deal with people’s preconceptions. In 1994, for instance, a wine writer from San Francisco was in the area but he did not visit the winery. Parker’s publicist sent him a couple of bottles of wine.

“In a subsequent column, he wrote that he had been in our area and he’d driven past our winery and he had thought, ‘What does an old television actor know about making fine wine?’” Parker said. “And so he just passed on. He wrote that ‘mysteriously’ a couple of bottles of wine appeared on his desk and that he had an opportunity to try them and he wrote that ‘they went extremely well with crow.’” The Fess Parker Winery business continued to grow. Parker worked with IBM to establish an operation to sell his wine via the internet. The winery was now receiving sales orders and wine club memberships and directly hosted the rapidly-growing Fess Parker Wine Club. In six years, annual wine production increased from 4,000 cases to 35,000 cases marketed nationally.

We talked more about the winery and then, finally got down to what were, for me, the real deal: his early life, movies, TV, and Davy and Dan’l. An only child, Parker was born in San Angelo, Texas, on August 16, 1924. “When I was six years old, my father sent me to his father’s farm and then I would spend two or three weeks there and then I’d go and spend two or three weeks with my grandmother on her Hereford cattle ranch. So, that was my life for the next 10 years; every summer I went to the farm and ranch and lived with my grandparents.” There were no children around, which, he said, “was both good and bad; I lived in an adult world and so it assisted me in certain respects. But I was a movie fan, I loved the Flash Gordon serials. And then I grew through the era of the big musicals and into the time where [director] John Ford and [actors] Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda and all those people began to make an impression on me. I have no idea why I decided I wanted to be an actor, but I just did.”

We talked more about the winery and then, finally got down to what were, for me, the real deal: his early life, movies, TV, and Davy and Dan’l. An only child, Parker was born in San Angelo, Texas, on August 16, 1924. “When I was six years old, my father sent me to his father’s farm and then I would spend two or three weeks there and then I’d go and spend two or three weeks with my grandmother on her Hereford cattle ranch. So, that was my life for the next 10 years; every summer I went to the farm and ranch and lived with my grandparents.” There were no children around, which, he said, “was both good and bad; I lived in an adult world and so it assisted me in certain respects. But I was a movie fan, I loved the Flash Gordon serials. And then I grew through the era of the big musicals and into the time where [director] John Ford and [actors] Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda and all those people began to make an impression on me. I have no idea why I decided I wanted to be an actor, but I just did.”

As a senior at the University of Texas, he met the veteran film star Adolph Menjou, who was a friend of one of Parker’s professors. “I was taking Russian as my undergraduate language and Menjou came to the Texas campus to narrate Peter and the Wolf. He was also to lecture about his experiences in Hollywood. They had 8,000 people come to hear that. I had a little car, and my professor didn’t have a car so he sent me down to the railway station to pick Menjou up.”

Menjou and the professor had time to kill, “so I drove them around [on a tour] and then took him to my fraternity house and we had lunch there. Then I had a little party after Menjou’s performance for a few friends and the next morning when I took him to the station, he said, ‘Would you be interested in working in films, in westerns?’ And I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ He said, ‘Well, you send me some 8 x 10s. I’m going to do a picture with Clark Gable called Across the Wide Missouri with [director] Bill Wellman, he’s a good friend of mine.’ So that was all the confirmation that I needed that it was a rational idea. Not that anybody else believed it was rational.”

Parker as Crockett: Disney kept him from John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe.

That was in 1949 and, for the next six years, Parker struggled to succeed in his chosen profession. Luck finally dealt him a card. Walt Disney was looking for an actor to play Davy Crockett in a TV series. Someone suggested James Arness, pre-Gunsmoke, who was then starring in a sci-fi thriller called Them! Disney screened the movie and was more impressed by Parker, who had a five-minute role as a man who had been terrorized by a giant flying ant. Parker was signed to a seven-year contract.

“I was thrilled to have Walt Disney as a producer,” Parker noted. “He put me under a personal contract. I thought that was wonderful.” When the three-part Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier aired on Disney's Disneyland series (as the first true mini-series), no one expected the deluge: millions of children sang the No. 1 theme song ("Davy, Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier"), store owners frantically stocked their shelves with coonskin caps and toy muskets, critics and historians heatedly debated the accuracy of the Crockett depiction in magazines, newspapers, and radio shows, and schools were renamed in honor of the man who died at the Alamo. Surprisingly, the long-dead Crockett was even elected to a local political office as a write-in candidate.

Davy Crockett comic book.

“I think in hindsight it’s a miracle that someone didn’t put two and two together and say that when Walt Disney produced a television series for the first time that more than likely the world would pay attention.” He added: “It was so intense, it was amazing. [The 'Ballad of Davy Crockett'] was number one on the Hit Parade for four months.”

Parker was catapulted to instant fame but for the star, it was a mixed blessing. As an actor, he wanted to grow. As a performer, he relished the limelight. Things didn’t turn sour for him, however, until he renegotiated his contract with Disney, Now a star, he wanted a star’s salary. Disney, of course, felt he had made Parker and had a Svengali-style interest in – and an exclusive contract to guide – his young star’s career. Disney was, Parker recalled to me, a “great guy, liked him a lot. He was somebody I understood; he was from a small town, but a brilliant man.”

Daniel Boone comic book.

Parker expressed mixed feeling about that time, about the might-have-beens. “It’s kind of a strange thing. I had two opportunities to have a broader career; I don’t know if I would have maximized them but I didn’t get the chance. One was John Ford wanted me to do The Searchers with John Wayne and Walt Disney wouldn’t let me do that. In fact, I didn’t even know it until it was already done. Jeffrey Hunter was my co-star in The Great Locomotive Chase and we were driving from Atlanta to the location and Jeff was sitting next to the driver and Walt and I were in the back seat and Jeff, just making conversation, said, ‘I just had the best experience of my life.’ 'What’s that?' And he said, ‘Doing a picture with John Ford called The Searchers.’ Walt turned to me and said, ‘They wanted you for that.’ That was the first time I’d ever heard of it. Then, later, when Marilyn Monroe was going to do Bus Stop, I knew about that play and I took it over to Walt’s office and said, ‘I’d like to play this part.’ And he read it and wrote me back an inter-office memo that said, ‘From Walt to Fess, I don’t think this is the kind of part you should do, Walt.’” Parker was disillusioned and became more so when Disney turned distant after the salary renegotiation. A notorious tightwad, who saw his actors as his “children,” Disney was presumably hurt by Parker’s attitude.

Parker and Patricia Blair on Daniel Boone.

“There was a point where two or three studios wanted to share my contract with Walt and he said no, and then in the end, after I was a couple of years into my deal, Ray Stark became my agent. He asked for a raise and got me a substantial raise, but Walt didn’t want to pay that, so he put me under contract to the studio [and gave up personal management of me]. And there was absolutely no idea what to do with me there so they started giving me featured parts.”

That meant small roles in pictures like Old Yeller, where a dog and his boy were the true stars. Finally, Parker was offered a role that was essentially a voiceover. “I had about five pages. So, I wrote to Walt and I said, ‘You know, I can’t do this.’ ‘Why not?’ I said, ‘Well, are you going to [bill me as a] co-star in this picture?’ ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Well, I haven’t any part, I think it’s dishonest.’ And I said, ‘I can’t just go backwards like this.’ Well, he disagreed, he didn’t take that stand and he got Bill Anderson who was his VP and hatchet man, to take over [talks with me] and I just said, ‘I’m not going to do it.’ And with that – they were unhappy and I was unhappy – we cancelled the last five years of my contract.”

Since Parker considered Disney a father figure and mentor, the move “really was a cataclysmic thing for me, emotionally. I’d found a home, I’d found a father figure and then I had to do that. I learned a long time ago that here are just things you have to do, you can’t… If you don’t do them then you’re sunk-you just lose your confidence and you have to do it. So, I left the studio and a few weeks later I was under contract to Paramount and that was fine.”

Parker paused. He was very forthright and straightforward, with a folksy, familiar manner of telling stories. I found him easy to engage, and he apparently felt the same way about me, at one point noting, “I’m enjoying talking with you.” We both ate blueberry pancakes. He occasionally took calls in a little cell phone, which seemed tiny in his huge hands.

He talked, briefly about his post-Davy film career – and briefly was the best way to talk about it. He appeared in television (on Death Valley Days and General Electric Theater) and as Sheriff Buck Weston in the movie, The Hangman (1959); then he had a small part in the Steve McQueen war film, Hell Is for Heroes (1962).

In 1962, he inherited the James Stewart movie role in a TV version of Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a one-season sitcom that he remembered vaguely. Then, NBC approached him about doing a TV series about Davy Crockett. “Walt had The Wonderful World of Disney on Sunday nights on NBC, so he said, ‘No, I don’t want to do that. Yeah, I think I’ve got these five hours of Davy Crockett and I don’t want to dilute them.’ So, he actually stopped it until somebody said, ‘Well, why don’t we do Daniel Boone?’ Which presented me with a little bit of a problem; I was already typecast as Davy Crockett for 10 years, now all of a sudden I’m going to put on a cap and say, ‘My name’s Daniel Boone and I live in Kentucky and I have a different wife and different children’?”

He wasn’t thrilled about the prospect but went along for practical reasons: “By this time, I had a family and I thought maybe this would be a security. Anybody that’s interested in the entertainment business has to have an unlimited capacity for insecurity. You just live in a dream world and sometimes the dreams come true and they’re not really the dream that you’re dreaming, it’s another dream that other people dream that you would want. But it isn’t necessarily what you want. I think if you really want to be an actor, you want to grow, you want the opportunity to have a satisfactory career, not one dimensional. And there are a lot of things that are so subjective. I mean, I’m 6 foot 6, I don’t necessarily fit in a normal milieu, if you will. People like Gregory Peck who are maybe like 6-2½, or 6-3, that’s fine. But [if] you just tower over people, it doesn’t work. I had a lot of reasons why the opportunities never came.” “Actually,” I said, thinking he was apologizing for Daniel Boone, “I think it’s superior to Davy Crockett as a series.”

TV Guide story on Fess Parker and his real estate deals, 1968.

TV Guide story on Fess Parker and his real estate deals, 1968.

“In a lot of ways,” he admitted. “I had a lot of good people. The first year was hell; we had several producers. We did 30 hours in the first year, in black and white and that was a double cross. I just made a condition doing the show that it would be in color. Well, I was already signed up, I’d made a commitment, and then they didn’t back me. [In addition,] it turned out that a lot of these people didn’t have any idea about the historical background of Daniel Boone and didn’t care much. So, I was rewriting on the set. And then that continued because the next year we had, I guess, multiple producers before a director, George Sherman, took over and got us through the end of the season.” But, he added: “I loved the ensemble effort of the cast and crew. We had the same crew for six years.”

Parker’s rewriting of the scripts was not generally known. “I was an American History major, got my degree in that at the University of Texas,” he noted. “I’d read a lot about Daniel Boone.”

Nonetheless, both the Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone series were filled with inaccuracies (starting with the fact that neither Davy nor Daniel wore coonskin caps). Boone, for instance, was not a “big man” in a physical sense: unlike the 6-foot, 6-inch Parker, the real Daniel was an ”average man,” coming in at 5-9 or so. And he was no slavery-hating liberal; like any good southern landowner, he had his share of slaves. He was also apparently more sexually active than his television counterpart: compared to TV Dan’s two kids, Israel and Jemima, real Dan had at least a dozen children Of course, he had no Oxford-educated Indian friend named Mingo, but one aspect of that relationship carried some truth: he frequently befriended native Americans, lived for nearly a year with the Shawnee Indians as the chief’s adopted son, and learned much of his backwoods skill from his dealings with native Americans.

The real Daniel Boone: no coonskin cap.

Daniel Boone generated much less heat than Davy Crockett but was a solid breadwinner over 165 episodes broadcast between 1964 and 1970 (it appeared in the 20 most-watched TV programs in 1968 and regularly beat its competition). Parker thought it could have run even longer, however, “but outside situations intervened. Twentieth Century Fox [the show’s producer] had lost an enormous amount of money with Cleopatra and they were selling off the back lot of the studio and so they needed money. So they took the show off the air and put it in syndication [even though] we had put away the Donna Reed Show and we put away the Red Skeleton Show, we put away Batman. And Cimarron Strip had gone bye bye. In 1968, we were in the top 20.”

NBC publicity magazine,1964.

But the series disappeared from syndication because Parker sued the studio over profits. “I had 40 percent of the net profits and was under the impression that I had a negotiated a reasonable contract as owner and co-producer. I was informed that there would never be any profits even though for five of the six years we had brought the show in under budget so there was money that could be anticipated. I was seven years in the lawsuit. But we did settle it.”

He got into real estate in the mid-1970s, after making a TV-movie (Climb an Angry Mountain) and turning down the role that Dennis Weaver made famous of cowboy-turned-big-city-detective Sam McCloud (“I didn’t want to do another series”). “In ’58, I actually bought a home and started coming to Santa Barbara and thinking of it as my place,” he said, explaining how he had turned to real estate. “But in ’60, I was married and I began to look at property. One of my friends was a contractor and so we built the mobile home park and that was sort of the beginning. Pretty soon, [because of real estate development,] I was independent of any financial [worries]. I found, much to my surprise, I felt a greater satisfaction and creativity in looking at real property. I think my strongest suit in real estate is not in execution so much as it is in concept and what you can do with something that’s unrealized.”

Daniel Boone viewfinder packaging, 1967.

Daniel Boone viewfinder packaging, 1967.

He was soon developing a successful hotel chain. “I had never thought about putting a hotel deal together, but it’s sort of a Texas trait—I was talking with some friends about it the other night—there’s some sort of cultural thing in the Texas makeup, you know? Here’s a hotel that needs to be built, you don’t necessarily have to know a lot about it, just do it, you know? Just start. And so that’s what I did. I mean, I ended up with 32½ acres of downtown Santa Barbara waterfront and what the city wanted was a hotel conference center. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll build it.’ Didn’t have the slightest clue how I was going to do it and it was a very unusual, complicated way that I worked it out, but I did and I’ve got one more to build.”

We talked about the winery again, touched on politics (a Republican, Parker had thought of running for the Senate in 1985 but abandoned the idea), and then I asked him how he thought he stood when compared to the real-life Boone or Crockett.

“I would come up way short,” he said quietly. “I’ve benefited from the adulation of people who enjoyed the shows but you know, people are just people and the experience causes you to be more conservative.”

“The experience of?”

“Being a public figure.”

“You mean more conservative in what you do because you feel you’re in the public eye?”

“Well, that and there’s a responsibility attendant to it. It’s a subtext; I do the best I can and I’m sure Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone in their lives did the best they could. And we look at them through this particular set of lenses because we’ve taken their lives into so-called entertainment. But the reality of their lives could be, as some people insist, quite different.

“Well, that and there’s a responsibility attendant to it. It’s a subtext; I do the best I can and I’m sure Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone in their lives did the best they could. And we look at them through this particular set of lenses because we’ve taken their lives into so-called entertainment. But the reality of their lives could be, as some people insist, quite different.

“It’s a strange thing, you know? Everybody thinks their world is the world and as a matter of fact, you know, it isn’t, but you can live with that illusion that your world is the world and it’s the most important world and that everybody’s paying attention to it. That’s the way actors tend to think. And then you find out, well, really, you’re in a comic strip. You’re not taken seriously as an individual, you are suspect because you’re part of that industry. What kind of work is that? What is that to somebody who’s doing some pretty heavy-duty labor, however you do it? You take an actor and you say, ‘Well, you can’t act anymore,’ what the hell do you do? I mean maybe you can sell real estate; some have, beautifully, very successfully or do something else; you name it. At the very least, they’re a resourceful kind of group if they’re not somehow or other incapacitated by their ego. I grew up out on the farm and ranch if something didn’t work you’d get a piece of baling wire and maybe tie it back together and then it’d work, you know? You find a way.”

And so the interview ended. He signed a photograph for me, posed for pictures, and I never saw or heard from him again.

I thought of all this the other day, when I heard the news that Parker, 85, had died. I remembered my interview with him and a story my father had often told about my youthful obsession with Parker’s Boone, the man who tamed Kentucky. When I was 10 or 11, I complained to my father about our family’s annual summer trips to Greece. Oblivious to the beautiful sun and sand, I longed for a different kind of setting, one that existed (although I didn’t know it at the time) only on a Hollywood soundstage. “Greece again?” I would sigh, jaded world traveler that I was. “Why do we always have to go to Greece? Why can’t we go to Kentucky?”

Now Parker was gone, but for one brief moment, I had met Daniel Boone. I had gone not to the real Kentucky but to the never-never land of my dreams. I had met Dan’l and not found him wanting.

“Thank you for a pleasant visit!” he wrote on the picture he autographed. No, thank you, Fess. You really were a big man.

April 12, 2010

All memorabilia from Tom Soter's private collection.

Lalo Schifrin

MISSION: UNLIKELY

MISSION: UNLIKELY

I wish I could say I had an in-depth meeting with Lalo Schifrin, the composer of the Mission: Impossible theme (and also of scores to Dirty Harry, Enter the Dragon, and Rush Hour, among many others). But I didn't. Growing up, I was always a big fan of top action movie film composers John Barry, Jerry Goldsmith, and Schifrin.

When I became an adult (some would say in age only), I continued my interest in Schifrin's music, discovering his versatility: he composed classical pieces, was renowned in the jazz world (having come to America from Argentina as part of Dizzy Gillespie's band), and had composed sweeping romantic themes quite different from the funky urban rhythms of "Dirty Harry's Theme."

In 2002, a colleague of mine pointed to an ad in the Village Voice, announcing that Schifrin would be playing music with a jazz ensemble at the Blue Note in Greenwich Village. I persuaded my girflfriend to go – she hated jazz, which may be one reason we're no longer together –and down we went. The music was loud, the cover charge outrageous, but Schifrin did play "Mannix," and it was great to see him live at the piano keyboards. Boy, could his fingers move! Afterwards, I stopped him on his way out – as many in the room had done – and he graciously posed for a photograph with me.

The following year, he returned to the Blue Note for an encore performance. This time, I went with a childhood friend (and fellow Schifrin devotee) Alan Saly and my then-current girlfriend (she liked jazz, so that isn't why we broke up). The music was exciting (and still loud), he played "Gillespiana," his tribute to Dizzy, and he was still great at the keyboards. After the show, I stopped him again; he autographed the picture of us from the previous year (and I wished him a happy 70th birthday), and I asked him if he would pose for another picture, this time with my girlfriend and me. Again, he graciously said yes. We posed. And the camera didn't work.

"Try it again," I said to Alan, as we all got in our poses, with frozen smiles. Once more, with feeling. Nothing. I felt terrible. I apologized to Schifrin, who was becoming politely impatient, and then said, "Let's try it again." Nothing. The camera was blinking. The battery was dead. I thanked Schifrin, he smiled tightly – "What an idiot," he must have been thinking – and moved on. Dead battery. Mission: Impossible. Right. More like Mission: Moronic.

November 2008

Michael Caton-Jones

BRIDGET, MIKE, BOBBY DeNIRO...and TOM?

From 1991 through 1994, I was the New York correspondent for a new film magazine called Empire. What that meant was whenever there was a press junket (a gathering of reporters interviewing multiple stars of a new movie) or a one-on-one interview in New York, the magazine's editors would call on me to supply copy. Usually, this was straightforward stuff -- you'd go with a group of reporters, be taken to a room, and the group would sit in a press conference with a star, or a writer, or a director. Then after 20 minutes of asking questions and listening to other reporters' questions -- and dutifully taking down notes -- the group would be herded into another room where you'd meet another star/writer/director and the process would begin again. Then you'd go home and write up your piece as though you had an exclusive one-on-one interview with the star/writer/director, eve though -- if you so desired -- you could get through the entire interview without asking a single question, just relying on the questions of others to get you the info you needed.

From 1991 through 1994, I was the New York correspondent for a new film magazine called Empire. What that meant was whenever there was a press junket (a gathering of reporters interviewing multiple stars of a new movie) or a one-on-one interview in New York, the magazine's editors would call on me to supply copy. Usually, this was straightforward stuff -- you'd go with a group of reporters, be taken to a room, and the group would sit in a press conference with a star, or a writer, or a director. Then after 20 minutes of asking questions and listening to other reporters' questions -- and dutifully taking down notes -- the group would be herded into another room where you'd meet another star/writer/director and the process would begin again. Then you'd go home and write up your piece as though you had an exclusive one-on-one interview with the star/writer/director, eve though -- if you so desired -- you could get through the entire interview without asking a single question, just relying on the questions of others to get you the info you needed.

In any event, occasionally I'd get a call from my British editor telling me of an actual one-on-one interview that they wanted. That's what happened with Michael Caton-Jones. Who? That's what I said to myself when my editor said the magazine had set up an exclusive breakfast meeting for the two of us the next day. I, of course, acted as though I knew who he was. I later found out that he was the acclaimed, rising star director of Scandal, Memphis Belle, Doc Hollywood, and the flick he was currently promoting,This Boy's Life. (Years later, he also directed one of the Pierce Brosnan Bond films.)

For some reason, the interview was assigned on short notice. As I recall, I only had hours to prepare, and in those pre-video-streaming days, I didn't have enough time to actually see any of the Great Man's movies, just read brief plot synopses and reviews of them. As it turned out, this proved no hindrance at all because Caton-Jones, affable and self-deprecating as he was, only needed slight verbal cues from me to talk paragraphs about himself, his movies, and his influences. Luckily, I knew a lot about the third part of that equation -- his influences -- and could intelligently discuss The Seven Samurai when he referenced it while talking about his own work. Occasionally, he'd say things about his films like, "As you remember in Memphis Belle," or "that pig in Doc Hollywood was trouble," and I would agree with him and ask a follow-up question that sounded like I knew what I was talking about (something along the lines of, "And what did you do to deal with it?" or "And what happened next?" or simply, "Yes, really?" and that would set him off.

"The compositions in [Akira] Kurosawa's films are just extraordinary," he said at one point. "Extraordinary. And that's something, unfortunately, that's not paid enough attention to in American cinema. They don't compose for emotion. You know, it's an old-fashioned technique. If you look at Kurasawa's compositions, or John Ford's compositions, or at Howard Hawks', they are all stylistically different. It's an art form -- and I don't want to let it die out. It's beholden to us to try and take the past and turn it into the future."

Still only 35, with a stubbly beard and a thick Scottish accent, Michael Caton-Jones seemed to me to be an unlikely character to be talking John Ford, or even to have handled the diverse themes of his first four movies: political drama (Scandal, 1989), war movie (Memphis Belle, 1990), "screwball" comedy (Doc Hollywood, 1991), and Coming Of Age story (This Boy's Life, 1993). It didn't seem unusual to Caton-Jones, however, who appeared to thrive on diversity.

"There's a terrible blandness about Hollywood," he complained. "So many people are terrified of losing a job. I think fear is the most dominant factor in Hollywood: fear of having to take the blame. If you're prepared to say, 'It was me, I'm responsible for this $40 million failure,' then you're ahead of the game from the start."

Not that Caton-Jones, one of the most successful graduates ro emerge from Beaconsfield's National Film and Television School (NFTS), had failed. Far from it. "All of my films have made money," he asserted. "If they make back their cost, they've made money." But then he was on to another subject, talking and talking and talking. ("Michael has a gift of the gab," the actress Bridget Fonda said to me later. "He loves to talk.") He started lambasting the state of the British film industry.

"It's in the toilet," he said bluntly. "It's been on its deathbed since its inception. I've got to say, having gone to Hollywood and made films, that we have no idea of what a resource we've got in Britain. We have some technicians who are without equal. Spielberg and Lucas came to London to make Star Wars and Indiana Jones. They didn't go there by accident, they went there because they could get the best technicians in the world to work on films at a slightly lower tax rate. For a government to start to tax people out of existence is a foul piece of mismanagement."

He added: "People fascinate me, because there is nothing more unexpected than the behavior of someone, you know? You've got to try and understand why they do what they do. Things don't just happen. They happen because of some reason somewhere. But that's the interesting thing, trying to find out. You can know someone for years and they can still surprise you."

Near the end of the interview, as the director sat across from me at a table in his hotel suite where we had been eating breakfast, he said quite casually, "Would it help your article if you could talk to some people who have worked for me?" I nodded my head, downing another glass of orange juice, and said, "Sure."

That was how the phone calls began. It started the Sunday after the interview. Returning home, I flipped on the answering machine and heard an unfamiliar but attractive voice. "Hello," it said seductively. "This is Ellen Barkin. I'm calling reference to an interview I believe you've done with Michael Caton-Jones; Anyway, I'll give you a try back later." Then, another message: "Hey, Tom! This is Eric Stoltz. I'm calling from Vancouver about that funny Scot! Catch you later!

Next up, "Mike Fox," affable and sounding like we were old pals: "I'll try you tomorrow," he said. failing to clarify whether he was, as I suspected, Michael J. Fox of Hollywood. Before I could mull this over for very long, the telephone rang. The woman at the other end of the line seemed very concerned. '"This is Bob De Niro's assistant." she said. "I'm calling because Bob wants to know if it's too late to talk to you. And when is the absolute latest he can call? He has a personal matter that will take him out of town, but wonders if Saturday will be okay. I assure you, he wants to talk to you very much."

As the week passed, my answering machine continued to be clogged with messages from very famous film stars. Take Monday, for instance: "Tom, this is Kelly from Woody Harrelson's office, calling about when he talk to you about Michael Caton-Jones, I'll call back." Then: "'Hi, Tom. This is Bridget Fonda calling. I'm sorry it took s long to get to you. I've been crazed, and I'm trying to think of something nice to say about Michael Caton-Jones. I'm just kidding. We love him, We love the loony guy. Anyway, I guess I'll try you later on. All right, bye!"

Then on Tuesday: "This is Kelly. Cheers is running long today, but I will try to get Woody to call you today, if not by Friday." That was followed by: "I'm calling for John Hurt, who is in Dublin. He wants to know when a good time will be to call you." Followed by a slightly anxious but playful-sounding feminine voice: "Tom, it's Bridget again. Hmmm. When can I reach you?'"

On Wednesday, feeling a bit strange, I left a message for these desperate people, detailing (in those pre-cell phone days) when I would be home to talk to them.

"Hi! It's Bridget calling - Bridget Fonda, I'll just assume that outgoing message was meant for me. If anyone needs to reach you -- that would be me. I guess I will give you call. I'm doing a press junket this weekend. When I have some time, I'll just give you a call. Is that okay? Thanks, and I'm sorry about the hassle. All right; byel"

And so it went. My week as the sought-after phone pal of the stars -- Mike, and Bob, and Bridget, among others. I spoke to them all, but our friendship was brief and my fame fleeting. When, months later, I was at a press junket for some new film starring Robert De Niro, I found myself at a table with five other journalists talking with De Niro. At one point, I reminded him of our brief interview some months ago about Michael Caton-Jones. While he still had fond memories of the director, old "Bob" had no memory of ever talking with me. Ah, how fleeting is fame! Luckily, I never ran into Bridget again. Having her acknowledge that I was nothing to her would have been too much to bear!

April 6, 2010

Overheard on a Bus

I had just gotten off the subway at Broadway and 116th Street when I noticed an M104 bus getting ready to depart. Now it's only a few blocks to my home from there, but it was a cold night and I was tired, so I put on a burst of speed and rushed to get on the bus. The driver opened the doors for me, and as I got on, I heard him mumble something about unusual traffic. I looked out the front window and sure enough, the traffic was inching along slowly, bumper to bumper. Well, I thought, it's cold outside and warm in here.

As I settled down, I looked around at my fellow passengers. They were the usual idiosnbcratic collection of Upper West Siders you usually find on a bus near Columbia University. But one man caught my eye. He was an elderly, well-dressed black man sitting near the driver, wearing a brown beret, nondescript coat, and glasses. He had a Clark Gable moustache and seemed like about a hundred other senior citizens you might or might not notice on any bus or subway. He was speaking in clear, firm tones to another man – this one younger, balding, wearing what seemed to be a Ralph Lauren top coat and Tsubo shoes.

"You have style," the elderly man was saying. "I imagine you were born with style."

The younger man seemed embarassed but pleased. "Well, thank you," he said.

"I tend to notice things like that because I'm an intelligent man." The senior paused and looked his fellow rider up and down. "My, but you have style."

"Thank you, thank you."

"If other people don’t comment on it, it’s because they envy you. I’m well-educated, so I know."

Neither man spoke for a few moments as the bus inched along in the congested traffic.

"I’ll probably see you again," said the older man. "I ride this bus often." He held out his hand for a handshake. "I’m Leon."

"I’m David." They shook.

"Well, I’ll be." He paused and looked the man up and down. "That’s my son’s name. David."

"Uh-huh."

"My son committed suicide three weeks ago."

"I’m sorry."

"That’s OK." He paused, as though in thought. "I saw you, and for some reason I talked with you. And your name is David. He’s still with us. His spirit is still with us." The younger man didn't speak, and the older man continued: "I’m 72 years old." He paused, and then said, in the same matter-of-fact way: "You see, I spent ten years in a federal penitentiary. They put me in there because they wanted to put away people like me."

"Really?"

"Sure." He seemed to have come to a decision and reached into his pocket. "I want to give you something." He pulled out a newspaper clipping and pointed to a person in what seemed to be a photograph. "That’s me. I was 22. I was his bodyguard." He was silent for a moment and then said, again matter-of-factly: "You know, I was visited by the FBI. They wanted me to work with them. They said to me, 'Do you like your family?' I didn’t know what they meant. But I was 33 when I got out of prison." He looked up. "Oh, here’s my stop. Nice talking with you, David." He got off the bus, exiting through the front door. David was going out the back door when I stopped him.

"Who was that?" I asked. "The person in the clipping? Who was it?"

"It was Malcolm X," he said quickly, rushing off the bus, as though he were afraid that I, too, would start speaking to him. There's a reason New Yorkers don't talk to each other, I thought, as I walked from the bus stop to my home. When I got there, I told the story to my girlfriend, Christine, as she was preparing dinner. At first, she was only half-listening, but by the end she was all ears and said, "Why don't you Google him?"

"Who?"

"Leon."

"I don't know his last name," I said.

Nontheless, later, as I sat at the computer, I typed in the words, "Malcolm X" and "Leon," and saw a number of entries appear. I picked a selection and started reading, feeling not unlike a character in a predictable thriller. But this was real, I thought, and I read on with curiosity. There was a lot about the shooting of Malcolm X, about an accused bodyguard named Talmadge Hayer who gave testimony about the death of the civil rights advocate nearly 50 years ago. The oft-told story that was repeated here was that Malcolm was betrayed by his bodyguards, who shot and killed him, and one conspiracy theory after another posits that the FBI was behind it. According to the entry I was reading, Hayer asserted that he and "a man named 'Lee' or 'Leon,' later identified as Leon Davis, both armed with pistols, fired on Malcolm X immediately after the shotgun blast [into Malcolm]. Hayer also said that a man named 'Ben,' later identified as Benjamin Thomas, was involved in the conspiracy... As of 1989, Leon Davis was reported to be living in Paterson, New Jersey." No mention was made of a son named David.

December 17, 2013

Patrick Macnee

A CLASS ACT

By TOM SOTER

When I tell people that I admire the work of Patrick McGoohan, many often look blankly at me, which invariably prompts me to say, "You know, the British actor who played a spy on TV from the 1960s." And then a look of recognition appears and the reply will be: "Oh, right, from The Avengers."

Right genre, wrong series.

It was 2000 and I was working on my second book, Investigating Couples, an examination of the connections among three series: The Thin Man (from the 1930s), The Avengers (from the 1960s), and The X-Files (from the 1990s). At the time, A&E Video was just releasing an authorized DVD edition of The Avengers, and through the good graces of a publicist at A&E, I not only got copies of the series, but also an opportunity to interview (though not meet) Patrick Macnee, who played the suave secret agent John Steed on the 1961-1969 series.

He was living in California now, forsaking the damp weather of England for the sunny climes of California. I called him at the appointed time and was excited to hear the familiar voice at the other end of the line. I thought we would talk about The Avengers straightaway, but Macnee began a long, rambling tirade against international immigration rules and customs officials.

"David Frost once asked me why I refused to return to England. And I said, ‘Frankly, until you let my wife’s dogs into the country, [I refuse].’ They haven’t...because of rabies. My dogs haven’t picked up even a tick in 12 years. But they’re letting all the human rabies into Great Britain at this very moment as we speak through the Channel Tunnel – I call it this monstrous hole – and yet they won’t let [in] my wife’s little dogs. And David Frost said, ‘I think they’re changing the rules’ – which they just have last week, for every where in the whole world, including Slovonia and behind the Ural mountains and the depths of Istanbul. But they haven’t from the United States because it’s such a dirty, rabies-ridden community. The irony one has to employ to sort of understand the people who [make these laws]... they don’t let two little dogs in because of the quarantine. I find the anomaly quite ludicrous.”

It is a passionate, almost nutty monologue – a rant, even – quite unlike what I expected rom the man who was the elegant, oh-so-proper English gentleman spy, John Steed, on The Avengers. I began to worry that Macnee had gone round the bend.

But soon he was talking about the series, and this time he went on about James Bond. He recalled that he refused to be influenced by the cinematic superspy.“Somebody gave me a Bond book [at the time the series began] and said, ‘I think this will help you with your character.’ I read it and found it, as I always have, totally repulsive. Bond is a repulsive man. A sadist. He’s completely upper-class, frightfully snobbish. He’s exactly like Ian Fleming was. Ian died of drink and tobacco just like that, way before his time.No, Bond is totally reprehensible to me.”

Steed, he noted, was instead crafted as a parody of an English gentleman, but one who treated women as equals. His relationship with his first female partner, Mrs. Cathy Gale (Honor Blackman) was defined early on as one of mutual respect, tempered by Mrs. Gale’s dislike of Steed’s unscrupulous methods. She was the “know-it-all” to whom Steed came for assistance; he was the man with the mission.

“To me the great secret of The Avengers is the knowledge that woman can not only keep it going with men. but can top men, and can rescue men and they can treat men as their friend and equal without emasculating them,” Macnee said, finally sounding more rational. “There’s too much made of male-masculine thing, I think. ” The live-on-videotape aspect of the series added to the excitement of the show’s early years. “The point is live television is live television,” Macnee said. “I did that in New York in the ‘50s and you’re not at your best, let’s face it. You’re sort of tentative, you’re nervous...When you have to do a series like The Avengers which, for four years was live [on tape], you really had to be on your toes. And I think if you’re on your toes, your brain works better, and I think what I did show in that show for all those years was a brain and [that I was] a sort of alert person.”

“There were no retakes,” Blackman told me later. “If somebody died in front of the camera, you stepped over them and took their lines. It really was a nightmare. I must say, that was one thing about Patrick. Sometimes, he used to wing it. And he would always, miraculously,. get back to your cue. It was quite extraordinary. You’d think, ‘Now where’s he gone now? Will I ever be able to answer the sentences made?’ And then he’d always come back to his cue. He was quite amazing like that. I’m a very solid performer. I like to know what I’m doing. And certainly if you’re working with someone like Patrick who flies occasionally, it’s as well that one of us is the substantial person.”

I had the same feeling when talking with Macnee. He would wander off subject, talking about dogs and videotape pirates, but then, with wit and verbal adroitness return to the subject at hand. In the end, he was as gracious and charming as I remembered Steed to be.

That wasn't the end of Macnee and me. My next contact with him came when I sent him a copy of the published book, sometime in 2002. Most interview subjects, I have found, rarely respond when an article I have written appears – unless there is an egregious error. (And even then, sometimes, they don't speak up unless prodded. I remember an early interview I did for a community newspaper with a polite Englishman named Timothy Dawson who ran a used bookstore. I called him after the story appeared on some matter and asked him how he liked it. He said, "It was terrific, Tom. There was just one little thing," he said with typical British understatement. "What's that?" I asked. "Well, my name is Mawson not Dawson." I was mortified, but he told me not to think twice about it.)

So it was with some surprise that I received a handwritten note from Macnee on his own stationary. It was a disjointed, rambling letter marked by an enthusiastic tone: "You got it right," he said at one point. He included a check for 10 books, saying he wanted to send one to longtime Avengers writer/producer Brian Clemens. The letter was signed, "Love, Patrick."

Eccentrically charming as this was, it wasn't my last contact with the actor. Some weeks later, I was about to appear a store event to promote my book. I was waiting to begin when I was told by a clerk that there was "someone named Patrick Macnee on the phone" for me. Thinking it must be a prank, I took the call. The familiar voice was on the line.

"Tom, it's Patrick here, just wanting to wish you the best of luck in your presentation tonight. And if anyone should ask, tell them that John Steed is alive and well and living in retirement in southern California. My very best wishes to you and success for you and your wonderful book."

Now, that's what I call a class act.

October 25, 2010

Patrick McGoohan

Patrick McGoohan, with TS, 1984

Patrick McGoohan, with TS, 1984

MEETING McGOOHAN

By TOM SOTER

There were three icons in my formative years (ages 12-17): Basil Rathbone, Sean Connery, and Patrick McGoohan. all of them were cool under pressure, all were men of action, and all were (fortunately or unfortunately) role models. Rathbone was, of course, Sherlock Holmes, Connery was James Bond, but McGoohan – well, he was special. He was the "Secret Agent Man," as Johnny Rivers's song put it in Secret Agent (aka Danger Man), he was No. 6 in The Prisoner, who would "not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered," who cried out, defiantly, "I am not a number, I am a free man." For a shy teenager, McGoohan's stubborn defiance of convention was breathtaking. Being McGoohan-like – aloof, taciturn, defiant of conventions – was making the shy guy into the cool dude.

I finally met the Great Man in December 1984. My editor at Video magazine knew of my fascination with McGoohan. The actor was appearing in his first Broadway stage production, Pack of Lies and would be available for an interview. But there would be restrictions: he would only sit for 15 minutes, and I could not use a tape-recorder unless he okayed it.

The interview was to take place on a Monday. I carefully prepared my questions and eagerly anticipated the big day. It came. He didn't. I got a call from his representative: "Mr. McGoohan is terribly sorry, but could he postpone the meeting until Wednesday?" Of course, of course. Wednesday rolled by, but McGoohan, once again, did not. "Mr. McGoohan is terribly sorry, but could he postpone the meeting until Friday?" Naturally, naturally. When Friday came, the call was expected. But this time, the interview was changed to Saturday, and when Saturday rolled around, there was no call of cancellation.

I went to the designated meeting place, a dance/rehearsal studio on Broadway and 20th Street. I went in and was told to wait in a dressing room for Mr. McGoohan, who would be with me shortly. Could this be happening? "Excuse me?" said a young man who appeared seemingly from nowhere, "What's your full name?"

I cleared my throat. "Ah, Tom Soter."

The young man nodded and went away. Outside the room, I heard muffled words. Then the young man returned, followed by a towering, wrinkled, slightly stooped figure.

"Mr. Soter, Mr. McGoohan."

He was much taller than I expected, over six feet, though the stooped walk covered it. He was clutching a book to his chest, the script for Pack of Lies. His face was lined, his forehead large, his eyes – peering through horn-rimmed glasses – quite blue.  Pack of Lies

Pack of Lies

"So, it's about The Prisoner you want to talk?"

"Yes."

He laughed quietly. "Well, I hope I can remember something about it," he quipped, adding: "It puzzled quite a few people, myself included, which was the point." He stared ahead, a classic enigma wrapped in a riddle, not unlike his character in The Prisoner. He suggested I conduct the interview at a neighborhood coffee shop that he had been eating at regularly during rehearsal breaks for the play. During the walk over, he made small talk. "We're at that awkward stage when you've just learned the lines and therefore haven't been able to do anything with them." He noted, however, that the play was in good shape as a production because it ran for a year in England and didn't need to be rethought. That was good, he added, because he found the challenge of acting in his first Broadway play sufficient. He had not appeared on the stage in over 25 years.

When we entered the restaurant, he nodded "hello" to all the waitresses, who smiled at him as if they knew him. A waitress came over and asked if we were ready. "I know what I want," he said, without consulting the menu. He lit a cigarette and ordered corned beef on rye. He turned to me after I had ordered. I took out my tape-recorder. He hardly seemed to notice it.

"Okay?" I asked.

He nodded. "Fine, fine." So much for eccentricity.

To start off, I admitted to him that I had always been a great fan of his work. He smiled slightly, perhaps pleased, perhaps embarrassed. Then he began talking about fans – about children watching his shows.

McGoohan, with Leo McKern (right), in The Prisoner

McGoohan, with Leo McKern (right), in The Prisoner

"That's one of the reasons I didn't want to use excessive violence on Secret Agent or The Prisoner. Television at the time was certainly a guest in the house. I felt that just as someone behaves properly towards a guest, it behooves one in playing on television to behave with a certain amount of – certainly we had fisticuffs and fights in Secret Agent but we certainly never had any sort of violence that would affect a child in any way or offend grandmother."

The producers wanted a James Bond-type hero, shooting off quips as rapidly as his gun and hopping into bed with a new girl every week. McGoohan had other ideas, however, and after seeing the first script wrote a long letter to the producer of the series, outlining what his character, John Drake, would and would not do.

"We eventually did it without any of that rubbish in it," he said, and his strong feelings led to the most unusual – and fascinating – secret agent to appear among the 1960s crop of Napoleon Solos, John Steeds, and Simon Templars. "You never saw me fire a gun," he noted proudly. And he never dallied with the damsels. "I said to the producers, 'If I start going with a different girl in each episode, what are those kids going to think out there?"

The conversation went on for 45 minutes, as we ate our lunch and drank our coffee. McGoohan seemed easy-going and unthreatening, like a real person not a TV icon. At one point, he took a drag on his cigarette and stopped talking. The words had seemed to flow out of him; he spoke in that curious mid-Atlantic accent, slurring some words, emphasizing others. He talked about the creation of The Prisoner, the story of one man's fight against a dehumanizing system. McGoohan plays Number Six, a secret agent who resigns his job and is spirited away to a sea town known only as the Village. Everyone has a number instead of a name.

"I'd always had these obsessions in the back of my mind for man in isolation, fight against bureaucracy, brainwashing, and numbers," remarked McGoohan. A visit to the Welsh resort town of Portmeirion, with its fairy tale-like buildings, inspired him; a talk with Sir Lew Grade fired him into action. Grade had financed Secret Agent and wanted McGoohan to do another adventure series. "I said, 'I don't want to do anything quite like that. I want to do something different.' He said, 'What?' So I said, 'This.' And I pulled out a script that I had prepared of the first episode of The Prisoner."

He said a lot more, but for me the memorable moments were the ones where he made me feel like a special friend (I'm sure this is an old actor's trick, but for an impressionable fan, it was heaven): when he noted at one point how perceptive I was, more so than most other people, and when he later hinted he might look at something I'd written and give his opinion, or see me in an improv comedy show. I'm sure he meant nothing by any of these things, but they made me feel like his pal.

After the meal, as we walked back to his rehearsal studio, I stopped a passerby whom I asked to photograph McGoohan and me. I remember the moment, but even if I didn't, the pleasure and pride and excitement I felt in being with my idol is palpable to anyone looking at the photograph of that moment. Was there ever a greater nerd than me? "It's only a TV show," I want to yell back at that dopey-looking, smirking kid with the silly moustache. But to me then – and, I guess, to me, now and forever – McGoohan and The Prisoner represent a period that I can never recapture but am constantly trying to, a time when I was always 14 and heroes like McGoohan were always there to keep us safe. "I am not a number. I am a person." Indeed.

TS in Portmeirion, Wales, 1990, location for The Prisoner

TS in Portmeirion, Wales, 1990, location for The Prisoner

November 2008

Raymond Burr

A VISIT WITH IRONSIDE

A VISIT WITH IRONSIDE

By TOM SOTER

As a journalist, meeting celebrities is par for the course. But meeting childhood heroes is something special. Sure, it was fun interviewing Robert De Niro, Michael Keaton, and Michael J. Fox. But meeting Patrick McGoohan, or Fess Parker, or Raymond Burr. Now that was something special.

The Burr interview came about through my own initiative. I had long been a fan of him in Perry Mason and especially Ironside (which I grew up watching on NBC), and when, in 1986 he was appearing on TV in his second Perry Mason comeback movie (the first having been a blockbuster hit in 1985), I thought he'd be available for an interview. I contacted his agent, set up the interview, got a photographer (Phil Greenberg from Habitat), and then sold the story to my editor, Ira Robbins, at Video magazine. Burr and I were set to meet in his hotel lobby. I was there ten minutes before our 1:30 appointment. At exactly 1:30, I heard a booming yet familiar voice coming from behind the chair in which I was sitting. "Mr. Soto," it said. I turned, and there was Burr looming behind me. He was a big man, maybe 300 pounds. "I'm Tom Soter," I said, correcting him. "I beg your pardon," he said, warmly shaking my hand and offering a pleasant smile. "Come with me." We went to his hotel room, and I noted there were a few unwrapped packages on the table by the couch. "It's my birthday," he explained, even though I had said nothing. "I'm 69 today." I wished him a happy birthday, we sat down, and the interview began.

Usually, Q & As like this are simple affairs: I would meet with the subject, we'd talk about his or her new project, go a little bit into his or her life and opinions, and wrap it up in a half-hour or so. Burr spent 90 minutes with me, and I've never known an interviewee to give such exhaustive answers to my questions. When I asked him whom he admired, he went through a list of about a dozen people, with detailed explanations of why they were important, starting with the pope and ending with his mother. He could also be very polite and charming but could just as easily turn on you, showing flashes of Ironside-like irritation at stupid questions (for instance, when he mentioned that he had his suits tailored, I said, "Really?" and he gave me a withering look and shot back, "Yes. Did you think I bought them off the rack?") Other times, he was solicitous and curious about me. He asked about my family and, when he heard that we were Greek, praised the Greeks effusively, asking if my mother was a good cook, and saying he must sample some of her cooking the next time he was in New York. He also praised me for my punctuality, saying he couldn't abide people who were late. "If that happens once, the next time I have an appointment with you, I won't be there," he noted. (His friendliness even extended to the photographer, Phil, to whom he said, "I have a photo project we should talk about.")

After an hour and a half of questions and answers, we posed for a photograph together. He put his arm around my shoulder, as though we were old friends. After that, I asked him if he would sign a photograph I had brought with me of him as Perry Mason. He smiled and said, "I'll be happy to sign this, or," he added suddenly, "I can sign the photo we just posed for if you send it to me in California. I'll do that on one condition, however. You must print two copies of the photo and send them both to me. I'll sign one to you – and you sign one to me." I was very flattered, and I thanked him for his time. Like an old friend, he promised to look me up the next time he was in town, told me to call him anytime I was in L..A., and even had his press aide give me a phone number at which I could reach him. I thought, "This is cool. Raymond Burr is my friend." A week or so later, Phil gave me copies of the photograph. I dutifully (and with some embarrassment) signed one, "To Raymond, from Tom (Soter)," and enclosed a note saying, "Here's the photograph you requested and also one for you to sign. Hope you are well," I added, as though we had known each other for years. I sent the photos off. And I never heard from him again. July 2008

Roald Dahl

When I was preparing my book on the James Bond movies in 1979, I wrote to the novelist Roald Dahl, who lived in England at the time, and asked him if he would talk with me about his experiences as the screenwriter for You Only Live Twice. He wrote me back a brief note that said, essentially, if you're ever in England, look me up. I took this as a polite brush off.

But I happened to be in the U.K. in 1980, and I called him. He didn't seem any too pleased to hear from me but did agree to talk, admitting (with ill grace) that he had promised to speak with me. After a bit of grumbling, he warmed to the subject and once he started going, he was quite expansive, talking not only about YOLT but also his experiences with the Ian Fleming film, Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang. By the end of the conversation, he had become quite cordial.

After I finished the interview (and a number of others, including talks with Bond folk like Tom Mankiewicz and Ken Hughes), I wrote the book – and then the project fell into limbo. My publisher, fearing a lawsuit, dropped out of the deal, and I was left with an unpublished manuscript.

When Dahl died in 1991, I saw an opportunity to use some of the interview material; so I sold a revised version of the chapter on You Only Live Twice as an article on Dahl and the movie to the magazine Starlog. In an ironic twist, that led to the publication of my Bond book. A small (very small!) publishing house (more of a hut then a house, actually) saw a note in the article that explained that the piece was adapted from an unpublished book on the 007 movies. The publisher, Ed Gross, contacted me, we agreed to go forward with the book, and the rest is the stuff of legend (at least in my household).

Bond and Beyond was published in 1993, and if you're interested, I still have a copy or two I could sell you (no kidding, click here).

April 15, 2011

Stan Lee

IF THIS BE MARVEL

IF THIS BE MARVEL

BY TOM SOTER

When I was three or four I was a big fan of Superman. I drew pictures of him constantly, the earliest of which showed him “flying” with feet that looked like flippers. I went to a school run by Episcopalian nuns and one year, when we were designing Easter cards in art class, I blended my fondness for the man of steel with the spirit of the season and whipped out a card with Superman as Christ on the cross (my dad loved it and had it framed; it reportedly was under consideration as a magazine cover on religion in the ‘60s).