Newspapers 1990-1999

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:4:]]

AHEAD OF THE TIMES

In the early 1990s, Long Island-based Newsday started a New York City edition of the tabloid newspaper. The paper had a weekly real estate section and I offered up a few ideas based on my experiences at Habitat. Dave Harrison, my editor, was a great guy and a good editor to work with. I did many stories for both the Long Island and New York City editions, often employing my sources from the magazine (one of them repeatedly asked me when I was going to quote him in Newsday). Unfortunately, when Harrison left in a buyout, I lost my connection with the paper (and the New York City edition was soon discontinued; it was later revived with little fanfare).

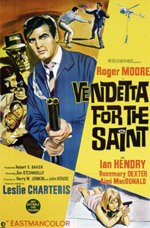

The other newspaper stories in this section are born of less-happy marriages between writer and editor. The stand-up comedy piece was one of two written for a Long Island edition of the Village Voice (the other was on the character The Saint). Although my editor said that she liked the story – and I was paid for it – it never appeared. The Upstairs Downstairs story for the New York Times is more problematical. I pitched the idea to an editor at the paper, and she wrote me back a strange letter saying that she liked my proposal letter, but that my sample story clips (all published pieces) were not "sophisticated enough" for the Times. That floored me, as few pieces in the paper seemed to me to be particularly sophisticated. This was, I think, a dodge on her part to get me to write the piece on spec (i.e., no promised fee, just a promise to consider the story). Normally, I wouldn't agree to such conditions, but hoping for a credit in the paper and confident of my abilities to write in a Times-like style, I accepted. I even agreed to a December 27 deadline, which meant working over Christmas holidays. I got the story in on time, of course, and then waited a week or two for the editor to get back to me. Finally, I called her – only to find that she had left the paper's full-time employment in a buyout some weeks before (naturally, a call to her writers was too much to ask). Her temporary replacement told me she'd look into it. Three months later – when the "hook" for the story, the release of the series on videotape and DVD – was long gone, someone got back to me. "The story has no hook any longer," I was told. And whose fault was that? The newspaper did pay me $200 for my expenses, however.

Adding Space

ADDING SPACE...

WITHOUT ADDING ON

By TOM SOTER

from NEWSDAY, JANUARY 1996

Alvin Wasserman had a problem in mathematics. He had three children, one of them a new baby, divided into two bedrooms. For his Rosyln Heights home, that was one body too many.

“For the first few months, we had a bassinet in my bedroom and the two other children each kept their own room,” he recalled. But as the baby grew, things became increasingly more cramped. “There isn’t a human being on earth who takes up more space than a baby,” he said with a sigh. “Their toys are bigger than the child itself. I told my wife, ‘Either the baby moves or I do.’ ”

The Wassermans’ solution was to put a bunk bed in one of the rooms and have the two older children double up. But for many homeowners, the problems are not so easily solved. Families grow, clutter accumulates, and space becomes scarce.

It doesn’t have to be. Experts say it is possible to add space without adding on. “A lot of older homes are very poorly planned,” said Martin Passante, the principal of MAP Architects in Hauppauge. “If you have an architect or interior designer look at your house, you can usually do a lot.”

Such work can range from major interior construction and renovation – knocking down and repositioning walls – to simple furniture redesign.The first step is to consider how your space is currently apportioned.

“Families have to decide whether it’s a good idea to keep a formal dining room or if they use it for something else because they always eat in the kitchen,” said Joel Ergas, a designer at Forbes-Ergas Design in Manhattan. “Often people have a dining room because it’s there. Maybe it makes more sense to turn that room into a home office.”

“It’s a matter of redistributing space according to how people live,” agreed Doris Milgrom, a designer in Great Neck. Sometimes that means radical redesign.

“I sometimes suggest they replan the interior of their home,” Passante said. “I’ve seen places where the stairs are stuck right in your face as as you walk in the door, where the kitchens are in front of the house when they would be better in the back. There are all sorts of badly planned things.”

In such cases, interior reconstruction may be the most efficient solution. In Passante’s own home, for instance, the architect took down the non-load-bearing walls and enlarged many of the rooms in the house. He transformed three small bedrooms into two large ones, and by so doing added enough space to the bathroom to include a large jacuzzi. Since he did much of the planning and contracting himself, the entire reconstruction cost under $10,000. He estimates similar jobs done by outside contractors could cost as little as $15,000.

According to interior designer Nicholas A. Calder of Manhasset, redesign and construction is usually less expensive than it looks. “It costs almost nothing to knock down a sheet rock wall and put up a sheet rock wall,” he said. “It is in the areas of plumbing and electricity where you run into cost. Carpentry and paint is the cheapest thing you can do in interior design.”

Hiring a designer or an architect is a good idea, he added, because “we’ll take a footprint of the home and with that make a diagram of how we can renovate. You’d be surprised at the amount of wasted space we uncover that way.”

You may even find space outside the house that you can convert. A little-used sun porch, for instance, could be enclosed with thermopane windows and turned into an extra room. “I’ve done that for people in homes and even for people who live in apartments,” Milgrom said. “It is an ideal way to give extra living space.”

Ergas said that when he examines homes in which there is supposedly “no space” he finds major construction is often not the issue. It is a question of “the wrong furniture. The place is filled with bulky pieces that had been brought from somewhere else and are too large.” He will often suggest smaller furniture or even custom built-ins.

Built-ins are inexpensive and can be very effective in eliminating inefficient furniture. Erik Kent, principal of Manhasset Interiors, suggested installing reading lamps and clocks to the bedroom headboard, which can “eliminate the need for small bedside dressers because you don’t need a place for the lamp and clock.” He also recommended removing lamps and some end tables by installing “high hat” lighting, lights recessed in the ceiling, which he called “more attractive than track lighting.”

Kent utilized both high-hats and built-ins at a kitchen he recently redesigned for a farm ranch home in Millbank.The space was tight, so he used high-hats to minimize tables and built in most of the cabinetry. But he also bought one piece of furniture, a hutch, that fit in perfectly.

“We needed even more storage space, but they wanted no more built-ins because it was starting to get expensive,” he recalled.“They didn’t want to custom-build this thing but they wanted something that fit into the character of the farm ranch. What’s nice about the piece I found is that it has the feeling and panache of a farmhouse, but fits into the new kitchen’s look. That’s why hiring a designer can be a good idea. He knows where to look to find such things.”

Other ways to increase space can include adding or expanding closets. “You can never have enough storage,” said Calder, who noted that many homeowners opt for furniture over closets, which he called a mistake. “People seem to love wall units. I’ve gone to 25 jobs where there are armoires, but do they have closets for their coats? No. Armoires are decorative but are not as useful as built-ins.”

One good place to add a closet is under a staircase, since the area is usually underutilized. Lawrence Laguna, an architect in Oceanside, suggested deepening a closet by taking unused space from an adjoining room. “Then you can add shelving in the back and places to hang things you don’t often use.”

In finding additional space within your existing closets, you should look for “places where you have height in the closet and aren’t using it,” Ergas said. “Some closets extend a number of feet above the door and you can’t reach that high.” One solution is to punch in a second compartment door so you can gain access to the upper reaches. Other times, two small closets sit side by side. Those can be combined into one large closet.

Extending kitchen cabinets to the ceiling is another way to increase space. Ergas recommended adding vertical storage drawers, which take up less space and can hold more produce than cabinets with doors. “They are like files for high-density filing,” he said. “If they are two-sided, you can put groceries on both sides. That way, you are making full use of existing cabinet space.” Another possibility: carousel units for corner cabinets.

Then there are bathrooms. In slightly oversized ones, Laguna said owners could building a shallow cabinet from the floor to the ceiling. “That can be a useful shelf space for towels,” he said. Ergas suggested adding storage units that straddle the toilet tank.

In doing such work, it is important not to make existing space seem smaller than it is. When Kent renovated a colonial home in Oyster Bay Cove, he used sconces and a crystal chandelier rather than high hat lighting to create “the feeling of a majestic formal dining room,” he said. “High hats are more contemporary and the owner wanted a classic look.What we did made the ceiling look bigger because it gives you elevation. The sconces and chandelier also give the room warmth and character which you are trying to create without closing the room in.”

In any space situation, experts say the solution often lies in the problem. “You have to do a little self-analysis,” Ergas said. “Once you understand what you are dealing with, it’s easier to find the answer. If you can’t get into the closet because the whole floor is covered with shoes, the trick is to find a way to get the shoes off the floor.”

Car Show

700 vehicles plus celebrities, science and a charity "tailgate" preview.

More than just cars at 9-day auto show

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:324:]]

By Tom Soter

FOR THE PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER

I'm 40 years old and just learned how to drive. My next step? Probably a car. And for that, I and others in my position - could find one at the Phil adelphia International Auto Show. OK, I might not actually buy one there - I am. after all, from New York - but it's a great place to look. Even those not car·hunting might want to head to the con

Set up in more than 430.000 square feet in all the major exhibit halls of the Convention Center from Saturday through next Sun· day, the gathering will be more than a collection of salespeople hawking 1997 and 1998 models. There'll be celebrities. science competitions. a black·tie affair, and a chance to get your hands on the latest car models.

Car conventions and Philadelphia have had a long history, dating to 1904. Although there were only four dealers in those days. They decided that the best way to promote their products was to stage a flashy showcase of their latest autos. So, four years before Ford's first assembly plant opened. The Philadelphia car convention was born.

This year's event. presented by the Automobile Dealers Association of Greater Philadelphia. will showcase most of the major manufacturers' new production cars. race cars, show cars. and proto: types. They'll present more than 700 vehicles. including the Mazda Miata M Coupe. Eagle Jazz. Plymouth Prowler. Dodge Viper GTS Coupe, and the Dodge ESS mini·van.

New or redesigned production models being unveiled for the first time on the East Coast include the Chevrolet Corvette. the MercedesBenz SLK 230, and the Porsche Boxster. "These three cars are the talk of the automotive' world," says Bert Parrish. executive director of the local Automobile Dealers Association. Although this show is the latest in a line that has gone on for nearly a century. experts say things have changed a lot. especially in the last 20 years. "These conventions used to be more show business." says Andy Schupack. a spokesman for the show. "Twenty years ago, it was not unusual for the car manufacturers to hire entertainers like Gladys Knight and the Pips or Jay and the Americans to take part. and then unveil cars with colored lights and waterfalls.

"But people don't want that anymore. Even the 'turntable girls' those sexy women posing in front of cars on rotating plat· forms] have been replaced by trained product specialists. A lot more people want to come in and find out about the cars. There's less show biz, because people are showing up with copies of Consumer Reports and car magazines. They're on a mission. You didn't see that 20 years ago. Maybe that's because the car is such a huge investment now. A lot of people take their research very seriously."

Not that the entertainment side has disappeared entirely. Some attendees may have no intention of buying. but show up because of the circus-like elements that still exist. Celebrities are on hand. some more relevant to the event than others. Last year. for example. stock-car driver Jeff Gordon. winner of the 1995 NASCAR Winston Cup championship. was present one day from 4 to 6 p.m. PeopIe arrived at 10 a.m. to line up and see him answer questions. He also signed an estimated 2.100 autographs in just over two hours.

This year. the stars will include Donna D'Errico of Baywatch (this Saturday and Sunday from 2 to 4p.m.) and Terry Labonte, 1996 NASCAR Winston Cup champion (Tuesday from 6 to 8 p.m.). Also, attendees will see competitive events featuring the mechanical wizards of tomorrow. The big one is the fourth annual Greater Philadelphia Automotive Technology Competition finals for high school senior automotive students. Scholarships. prizes and trophies will be given to students scoring highest in hands-on skill contests. staged Tuesday morning.

In the. contest. pairs of teens diagnose and then repair a range of faulty cars. using whatever tools they have on hand as they try to beatthe clock. "They're like a pit crew in a racing competition."Schupack says. Berks Career and Technology Center-West. in Leesport. Berks CountY, Pa . has bested the competition for the last two years. going on to win at the National Automotive Technology Competition in New York in 1995.

There will also be a "Black Tie Tailgate" from 7 to 10 for $75. Guests can preview the show before it opens to the public, and enjoy hors d'oeuvres and cocktails. Proceeds benefit Children's Hospital' of Philadelphia. (Jnformation: 215-590-4008).

Of course. most people come for the cars.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:327:]]

"I've seen families of fiye or six arrive," Schupack says. "They do things they can't do at a dealership. If they heard that it's easy to take the seat out of a mini-van, then you'll see them yanking it out. Or if the seats are supposed to be real bouncy, then you'll see the kids bouncing around."

Many can also ask questions relating to the purchase of the automobiles choices. "Very few people decide what to buy at the show. but they can narrow down their options to two or three kinds of car. That's one reason the dealers and manufacturers are here in such numbers."

Attendance seems to grow every year. The move to the Convention Center from the Civic Center in 1995 might have made a difference. Things are newer and bigger – and the crowds have been sizable. Even though there were major snowstorms both weekends last year, 103,000 people showed up over the nine days.

The internet has also played a role. Discount coupons ($2 off one weekday adult admission) are available on the web. Show planners started experimenting with the cyber tickets six months ago; 500 people came to a show in Anaheim, Calif., with coupons they had downloaded.

Still, the need to actually see and feel the car is not likely to change. "Getting information through the internet will complement what we do, but it will never replace the show itself," Shucpack says. "It's an event you have to see."

January 10, 1997

Elevators

NOTE: The following is a portion of an article I saw published in The New York Observer, a weekly newspaper, in 1996, I believe. It was actually written for a proposed publication called City Legacy. When that magazine never flew, I recycled the story for the Observer (I don't remember if I added anything) and later reused some of it in a sidebar for Habitat magazine. Here is the Observer version.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1253:]]

QUICKER THAN CLIMBING STAIRS,

SAFER THAN WALKING

He was an unlikely visionary, a man who tinkered and toiled with various inventions in his lifetime. And although he died long before the first skyscraper was built, Elisha Graves Otis is the spiritual architect of modern New York. In fact, the city as we know it, owes its existence to the little box that Otis built.

We’re talking about elevators, the world’s most frequently used and perhaps most underappreciated mechanical mode of transportation. There are large elevators and small ones, ornate elevators and mundane ones. There are hydraulic and electric, glass and wood. In Manhattan alone, there are about 56,000 cabs, with the fastest (in the Met Life building) traveling at 1600 feet a minute (the fastest in the world is in Tokyo, operating at 2,000 feet per minute), and the slowest -- well, who knows?

"Elevators are the safest mode of transportation per capita per mile," notes one elevator repair technician. "They're safer than walking, than running, than using the stairs." The Buildings Department reports few deaths in elevators, and those are ususlly caused by human error, not mechanical failure.

Elisha Graves Otis didn't invent the elevator -- there had been horse-drawn hoisting devices as far back as the pyramids in 2600 B.C. -- but he did make it workable by creating the first "safety elevator." No wonder, too: Otis was a natural tinkerer. Born in 1811 as the youngest of six children, he abandoned his father's farm to become a master builder in Albany. Between 1834 and 1850, he went through a succession of jobs that were all tied together by a single thread: the need to invent.

"He possessed no ordinary genius as an inventor," his son Charles wrote in 1911. "He could invent, design, and construct a perfect working machine or improve anything to which he gave his mind, without recourse to any of the modern drafting room methods. He needed no assistance, asked no advice, consulted with no one, and never made much use of pen or pencil in designing his various machines...the desired result was reached by him more as an inspiration than by a process of slow, laborious reasoning and experiment."

Otis built a grist mill run by water power and worked at a carriage manufacturing plant and then a sawmill. He was hired as a master mechanic and soon devised a number of labor-saving machines. In 1850, he invented a set of safety brakes for a train company and that led him to the safety elevator. In 1852, Otis was asked to build a freight elevator for his employer, the Bedstead Manufacturing Company. Previous elevators all had a fatal flaw: when the rope broke, the cab fell. That created a widespread fear of the lifts that was hard to overcome. Even in the 1890s, when elevators were more common, many people still considered them unsafe, and some insurance policies even excluded coverage for elevator deaths.

Otis's innovations changed that. Accompanied by the motto, "Safe Enough for Grandma to Ride In," the new Otis elevator employed a brake. The inventor put a wagon spring on top of the hoist bar and ratchet bars attached to the guide rails on both sides of the hoistway. According to an account by the Otis Elevator Company, "the lifting rope was attached to the wagon spring in such a way that the weight of the hoist platform alone exerted enough tension on the spring to keep it from touching the ratchet bars. But, if the cable snapped, the tension would be released from the wagon spring, and each end would immediately engage the ratchet bars, securely locking the hoist platform in place and preventing it from falling."

The safety device was a success and the forerunner of present-day devices. Further development saw a speed governor in the control room, connected to the elevator by a rope. If the elevator goes too fast, the governor pulls on the rope, which slows or stops the elevator by released the spring-loaded wedges under the cab. These shoot out, grab onto rails in the shaft and stop the cab from falling.

The method is so surefire, in fact, that its most noteworthy failure is also its most extraordinary. In 1945, a low-flying airplane crashed into the side of the Empire State Building and sheared the elevator's cable and the safety rope. When the cab fell, the saftey wedges were not activated.

By 1854, Otis was exhibiting a working model of his invention at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in New York. When his rising platform, reached the top, 40 feet above the assembled crowds below, he had an assistant dramatically cut the hoist rope and, like a good showman, bow to the gasps of the onlookers when the elevator did not fall. The New York Tribune called the demonstration "sensational" (labeling Otis, "Mr. Safety Elevator Man"). In 1856, Otis erected what many consider the nation’s first regularly used passenger elevator in the new five-story E.V. Haughwought & Co. store at the northeast corner of Broome Street and Broadway. By 1861, when he died of diphtheria, Otis was doing a brisk business creating elevators for manufacturing companies. (And his legend was beginning to grow, as well, with his son claiming that his father was, improbably, a Civil War veteran and “without doubt a lineal descendant of the most distinguished family known to history, Adam and Eve.” )

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1255:]]

The evolution of the elevator might have stalled there, restricted to manufacturing uses, had it not been for steel-frame building construction. In 1885, W.L. Jenney designed the 10-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago. At the time, making buildings higher than six storys was impractical because of the huge brick foundations necessary. Jenney's "skyscraper" employed an iron frame to support the weight of the structure. The elevator allowed the hi-rise to be conceived. Soon, skyscrapers began rising with rapidity: the 22-story World Building in 1890; the 20-story Flatiron Building in 1903; the 41-story Singer Building in 1906; the 52-story Metropolitan Life Building in 1908; the 60-story Woolworth Building in 1912. Out of 800,000 buildings in New York, the buildings department reports that roughly 8,400 have elevators, mostly concentrated in Manhattan.

By 1929, as the Depression came down, more hi-rises seemed to be going up. Between 1929 and 1931, four of the tallest buildings in the world arose: the 71-story Bank of Manhattan (927 feet); the 66-story Wall Tower (950 feet); the 77-story Chrysler Building (1,046 feet); and the 102-story Empire State Building (1,250 feet).

As they were created, so were new laws governing the manufacture and safety of elevators. By the 1920s, there were two types of elevator in operation. The older models were generally either plunger or roped hydraulic elevators. The plunger style featured a cab built directly on a hollow piston that was moved in and out of a large cylinder by varying fluid pressures. In a roped model, ropes were linked to the elevator car and powered by a separate hydraulic piston and cylinder. Water from the water main and later under high pressure pumped by steam forced the plunger up and carried the elevator up. The relaxation of pressure allowed the plunger to sink, carrying the elevator down. (Modern hydraulic elevators use oil pumped by electricity.)

A quarter of the elevators currently in the city are hydraulic, usually found in such low-rise buildings as lofts. Hydraulic elevators were prominent at the turn-of-the-century, but controlling them was a little tricky: the water pressure could fluctuate and the elevator would bounce at the floor landing.

Traction elevators, employing electricity and counter weights, were introduced in 1889. They allowed for more precision in stopping and starting the cab, and also, eventually, greater speeds. According to the Otis Elevator Company: "The principle is similar to the operation of a locomotive pulling a train as the result of traction between the steel wheels of the locomotive and the rails. With an elevator, six to eight lengths of wire cable are attached to the top of the elevator and wrapped around the drive sheave in special grooves. The other end of the cables is attached to a counterweight that slides up and down in the shaftway on its own guide rails. The result of this arrangement is that with the weight of the elevator car on one end of the cable, and the total mass of the counterweight on the other, it presses the cables down on the grooves of the drive sheave. When the motor turns the sheave, it moves the cables with almost no slippage. The weight of the car and about half its passenger load is balanced out by the counterweight, which is [traveling] downas the car is going up. 'It supplies the necessary traction."

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1256:]]

Electricity brought further modifications: The elevator relays were programmed to make multiple decisions, doors with interlocks were mandated and door "operation was refined to provide safe automatic opening and closing. '

The last two were the biggest steps toward complete automation of elevators. In the 1890s, a number of residential buildings had self-service passenger cabs. These featured a shaftway door and, in the elevator, a gate that the passenger would open and close himself. Locks were devised to prevent the hoistway doors from being opened if the elevator wasn't there or to prevent the elevator from running if the door wasn't locked. When the inner gate was transformed into an automatic inner door in the early 20th century, safety edges were developed and added to reopen the door if anyone was in its path.

"In the 1890s, many people still considered elevators unsafe," observes Mr. Strakosch. "My father had an insurance policy that excluded deaths in passenger elevators." Otis's innovations were accompanied by the motto "Safe Enough for Grandma to Ride In."

In 1922, the city passed the first elevator inspection codes. Those required full load and stress tests. Current requirements call for two tests a year conducted by the city and one by an outside firm. There is also a stress test every two years and a full load test every five years, Mr. Tiryakian calls these requirements "the most stringent in the nation."

Elevators – then and now – are built in the shaft at the site, generally from prefabricated "parts." Most elevators have standard components, but from building to building, they are one of-a-kind," Mr. Strakosch says. "They are works of art."

“Early elevator designers as well as modern ones were very particular about how they created cabs. "The art of riding an elevator,".architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in The New York Times in 1977, "is a crucial part of the experience of a piece of architecture. 'There are no stairs to be experienced in a hi-rise building; we are forced to shut ourselves into a little box; and if that little box is designed to contradict everything else about the building, then the building's aesthetic message is garbled and ,compromised."

Although about two-thirds of the most beautiful cabs were destroyed in modernizations in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a number of striking "boxes" remain. At 230, ParkAvenue, built in 1929, the elevators feature elaborate paintings, gilt moldings and bright enamel walls. The Sherry Netherland, at 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, spotlights Italianate paintings on its elevator's ceilings. At 1 Park Avenue, 52-year-olld shaftway doors are embossed in bronze with the words "Fidelity, Sincerity, Integrity, Courtesy, Industry, and Amity." Radio City Music Hall showcases Art Deco doors and Greek motifs.

"These are the kind of things you see once in a lifetime," noted Yale Citrin. former president of Millar Elevator. When the firm was restoring the Plaza Hotel's cabs in 1977. “We are changing them as little as possible."

The biggest metamorphosis of recent times came, in the., 1960s, when office buildings converted entirely to automation. Cab designs were modernized, but so was the way elevators ran. "There had been automation available for a long time," says Mr. Strakosch, "but it was a sign of prestige to have an elevator operator. In the 1960s, they were gone."

In the 1980's, the big switch has been to computerization, notes Mr. Strakosch: '"They're adapting contemporar engineering – solid state computers –to improve performance. You don't want some people to wait too long and others to have instantaneous service."

Every major company has introduced microprocessor technology for elevator buildings with large and complex traffic patterns. One company, Westinghouse Elevator, explains in a sales brochure: "Every potential corridor call in the building is pre-assigned to an elevator before the call is actually entered. These pre-assignments are re-evaluated and redefined twice a second. In effect. the system is predicting, every half-second. which car will be in the best position to answer any call that may be entered in the next half-second, minimizin~ the response time of the elevator system ~ when a call has been registered. Registered calls are instantly assigned and the system is scanned 10 times a second for new calls being entered."

As for the future, the only major difference in the box that Otis built will probably be aesthetics: glass or gold-plated, chrome or wood, plastic or formica. But the basic concept will not change much: a box hooked to a cable running over a pulley. And why should it? Simple yet brilliant, Otis’ “Magnificent Moving Machine” has helped New York City grow and prosper. Mr. Elevator Safety Man would be pleased.

New York Observer, 1997

He's Got Legs

NEWSDAY, AUGUST 16, 1993[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1475:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:1473:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:1474:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:1479:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:1472:]]

Stand-up Comedy

LAUGHS ON LONG ISLAND

By TOM SOTER

for LONG ISLAND VOICE

Kevin James, sandy-haired and stocky, is dressed in black and has the energy of a dynamo. "You know what irritates me?" he says to an audience of mostly young people. "I was on the phone with someone today trying to get a phone number and write it down, but they didn't have phone number rhythm. You know what I'm talking about, don't you? Phone number rhythm. Especially where there's an area code involved." He pounds out the rhythm on his microphone: "BAAM BAAM BA." A pause. "BAAM BAAM BA BAAM." Another pause. "BAAM BAAM. That's the rhythm that we're all familiar with.

Kevin James: king of stand-up.

Kevin James: king of stand-up.

"I say, 'Okay, Hank, give me the number. He says, 'Okay, it's 2129.'" He pauses. "'1581120.'" He pauses "'9.'" James explodes in anger. "'What are you throwing me a zip code? There are two many numbers!' They screw you up with the last four. That's where they get you." He imitates someone giving out a phone number: "'782 - 6 - teen 41.'" He screams in manic fury. "'I ALREADY WROTE THE SIX! I made the dash too close, I can't shimmy the one in there!'"

The audience at McGuire's Comedy Club in Bohemia goes wild with laughter. But James is soon off on another bit, spitting out his words with good-natured venom that often makes him the hapless lead character in his stories of woe, the ironic butt of his own wry and wacky jokes.

Kevin James, 32, is hot. He's just shot a pilot for NBC (his second), he was a standout at the Montreal Comedy Festival a couple of years ago, and is now busy almost 52 weeks a year at comedy clubs through the country. Yet like a comedic salmon, he always returns to his spawning ground: the Long Island club circuit. "I love it here," he says. "This is where I started."

Long Island is a breeding ground for comedy. It is the creative (and sometimes actual) birthplace of some of the biggest stars in the comedy world: Jerry Seinfeld is a Massapequa boy, Rosie O'Donnell comes from Commack, and Eddie Murphy hails from Roosevelt. And all of them honed their comic personalities in the Long Island club circuit. And it's no wonder. The Long Island comedy club scene is as versatile as the comics who perform it, offering a range of material and a host of opportunities.

There are off-color, absurdist gags. "They didn't tell us everything in sex education class," Lenny Horowitz, a young comic who looks like Murray the Cop on The Odd Couple, complains one night at McGuire's. "They tell you that the penis enters the vagina - maybe on a good night - but what about all that other stuff? You know, like, the penis enters the flower shop. The penis buys the chocolates. There's a whole process. They told us where it goes, but they didn't tell us how to get it there."

There are puns on names. "My name is John Priest," says a young, thin, clean-cut man appearing at Governor's Comedy Cabaret and Restaurant in Levittown. "It's kind of a strange name, considering I'm Jewish. I think I'm the only Jewish Priest. Imagine if I had gotten serious about the religion and gone rabbinical and I'm paged in a restaurant, 'Rabbi Priest, you have a phone call. Schlmo Christianson.'"

Naturally, there are digs against wives. "I'm married," explains Buddy Fitzpatrick, a thin, rubber-faced comic appearing at The Brokerage Comedy Club in Bellmore. "Let me share this, from the guy's point of view. Do you love him the way he is?" he says to a woman in the audience who has revealed she is about to be married. "Yes? Well, remember that five years from now. He doesn't know this yet, but he's about to change. When you get married," he observes, indicating himself, "you have to change. And she doesn't. There's one reason my wife and I argue. I do something wrong." He repeats it, with an emphasis on the personal pronoun: "There's one reason my wife and I argue. I do something wrong."

Some comics are not overly subtle. Cigarette-smoking Joe Moffa at Governor's offers a deadpan view of wedded bliss: "I'm gettin' divorced after 12 years of marriage. That sucks. I should have killed my wife the first day I met her. I'd be out of prison already. That's what I think about marriage."

Such comedy may be universal, but Long Island both onstage and off is an unusual scene. Onstage, comedians get from 15 to 45 minutes of performing time, a great deal by most club standards. Because of that, Rich Brooks, a comic for only ten months, often finds himself commuting to Long Island from his home in Manhattan. "In the city, I'm fighting for a five-minute spot," he explains. "But at McGuire's, I get 15- to 20-minute spots in front of a large crowd. And I get paid."

"There are thousands of comics in Manhattan who have moved from Cincinnati and Florida and all around," observes Rock Reuben, a veteran Long Island-born and bred comic. "In Long Island, you have 20, 30 comics as opposed to 1,000 in the city. To get on stage in New York, people wait in lines around the block. Here, it's a little easier to get on stage. And if you can't get on stage you really can't develop."

"Development" is a common theme among the island's comics. If they have more time, they have more opportunity to work the room, entertaining their customers while developing material from the absurdities they find in their audience. Stand-up Joe Lazer, dry and sophisticated, found the give-and-take useful one Thursday night at Governor's when the audience wasn't terribly enthusiastic about his prepared gags.

"How many smokers we have here?" he asks. "Anybody quit recently? You did. How long did you quit for?"

A young blonde woman, chewing gum while holding a foot-long cigarette, replies with a nervous smile: "Two weeks."

"How'd you do it?" asks Lazer.

"I just didn't buy any."

The comic looks startled. "Ah-ha," he says finally, to the biggest burst of laughter he's received so far. "Why didn't I think of that?" He goes into a mock question-and-answer session with himself: "'How'd you kick the heroin habit?' 'Oh, I just didn't buy any. I got more money now. I quit buying.'" The audience is hysterical and Lazer, too, has picked up energy, feeding off their enthusiasm.

"Sometimes you can get a whole 10-minute thing out of an audience member's response, which for me is fun because it's not repeating my act," Reuben explains. Adds James: "It's exciting. It's live and anything can happen. And sometimes it does."

Although the audience can't tell, there is also less professional pressure in the island venues. "Agents don't come out here," says John Ryerson, the owner of McGuire's. "So the comics can start developing longer material without industry pressure." Adds Reuben: "You can grow. You can suck and not have to worry about it, where in the city somebody could see you learning how to do the business and categorize you as a shitty comic and not want to see you after that."

The comedy clubs themselves are as different as the comics that perform in them. Governor's, adorned with 3- by 4-foot pictures of Laurel and Hardy, Charlie Chaplin, Abbott and Costello, and local comedians Bob Woods and Bob Nelson, is widely considered one of the top clubs, with out-of-town headliners performing there on Saturday nights and locals in on other nights. The Brokerage, in business 16 years, features local and national talent, as well. And then there's McGuire's, the quirkiest of the lot, low-key and informal, more like an upscale cafeteria than a club. Reuben is amusingly vicious about it as he takes the stage on one Saturday night.

"I hope you all found the club easily," he says. "I know when I first came it was a little hard to find. They give you the clear directions, 'We're located right behind Appleby's Dumpster.' I found it. I just followed the trail of rat shit to the club and you just know, 'I have no career. I'm in Bohemia again.'"

There is a blue curtain behind the stage; taped on it is a sign made out of five pieces of 8 1/2- by 11-inch pieces of paper taped together. On it, in computer type, are the words "McGuire's Restaurant and Comedy Bar." (By contrast, Governor's and The Brokerage have hand-painted wooden signs with fancy logos.)

"This is one of my favorite clubs," continues Reuben. "I love coming back because of the attention to detail of John, the owner. He goes the extra mile. A lot of the owners are cheap bastards. Not John. He'll take some of the [profits] to reinvest in the club. Because shit like this," he indicates the sign, "has a price tag. Look, from the back you can't see - that's one, two, three, four, five pages that he had to print out and I'm sure there were two or three other pages that he printed up and got fucked up and he had to throw them away. But he's willing to go the extra mile. And he got the crazy fonts and graphics. And color! If you have a computer at home, you know hoe expensive the color cartridge can be. He doesn't give a shit. He said, 'Fuck it, they deserve it.'"

Comedy became hot on Long Island in the 1980s, when clubs were springing up all over the country. But now times are getting tighter and competition stiffer. "Business has leveled off," reports Andrea Levy, a talent coordinator for Global Entertainment Network East in Huntington, who is the exclusive booking agent for Governor's. "A lot of the clubs I book for around the country are complaining that business is down. We are giving out more comps [complimentary tickets], and making less money at door. Clubs are hiring telemarketers. We're trying to get people through the doors, and that's why we book big-name acts. They get publicity. You just don't get the turnover of people you used to. They can see it on TV. Stand-up has been overexposed."

With night spots looking for comics, the talent wars can become intense. Levy says that she requires an exclusive: if a comic is playing Governor's, he or she cannot play in competing Long Island clubs in the month before or the month after the appearance. She is strict about it, too, saying she has refused to book a comic for year and half now who wouldn't agree to those terms. Comics can get paid anywhere from $25 to $5,000, depending on the club and their reputation.

Times may be tough for industry, but they can be tougher for the comics if they don't know their customers. Stand-ups agree that audiences on the island are a special breed. "A lot of the comics who work just Long Island, do a Long Island-type of humor," says James, "then they go into the city and just eat it. Everything has got its own feel, and you've got to get your legs in each city, feel what it's like and see what hits home with them. And they let you know quick enough."

Adds Reuben: "It's not a general rule, but the guys who started out in the city tend to be more cerebral, lower energy, and a little bit more edgy. Long Island types tend to be a little bit more crotch-gas-bodily function [comedians]. They are louder, have more energy. It's power comedy. It's what people out here expect and it's what people in the city expect, so when you get the crossover, a loud guy doing fart jokes, that doesn't play well on the Upper East Side, and the cerebral guy talking about Dole and Gingrich doesn't play in Bohemia."

Long Islanders seem to love anything to do with their native habitat. "The L.I.E. sucks," says Buddy Fitzpatrick to roars from the audience at The Brokerage one Saturday night. "What's wrong with that road? Constant construction, constantly merging you in three lanes, merge to two lanes, merge to one lane. It dissolved to nothingness at one point and I appeared on the other side, like Star Trek."

"I grew up in Long Island," confesses Jeff Rogell, also at the Brokerage. "I'm Jewish and I didn't understand why we didn't celebrate Christmas. I wrote a letter: 'Dear Santa, I know you won't give me any toys because I'm a Jew. Your apparent lack of compassion towards the Jewish community is only a reflection of a racist policy of non-recognition towards the state of Israel. I hope you get clipped by a DC-10, you fat Nazi bastard.'"

Island audiences also seem to like people who point out the peculiarities of their neighborhoods. Kathy Walker, a heavy-set, young black woman, bounds onto the stage at The Brokerage, with good-natured energy. "Long island!" she cries. "The big L. I'm so excited about being here. My agent said, 'Kathy girl, you gonna love Long Island. It's gonna be a blast. So many black folk out there.'" The audience whoops with laughter. Then Walker notices a black woman. "Oh, hi! Are you black or just an Italian with a tan?"

"Where you from?" Rogell asks, at The Brokerage on the same night. "Queens. Uh-huh. I took a course in Italian martial arts. It's a lot like karate. Except there are two guys holding your opponent down." He acts it out with a Queens accent: "Alright, class, repeat after me, 'You fuckin' douche bag.'"

The chains of marriage, the oddities of foreigners (from cab drivers to neighbors), and the absurdities of mall life, shopping, and eating all seem to be staples of "island humor."

"Tonight, I had a pizza," James tells the crowd at McGuire's. "Ain't pizza great? You know what sucks, though, is to have it with other people. That's way too much pressure, especially when those slices get lower and lower, you gotta look around the room, do that pizza math." He lowers his voice, acting out his inner monologue, a tense moment when he is petrified by fear: "Alright, HE already had two slices. Hey! Maureen - what the FUCK is she doing? Setting the record for women? Slow it down! Finish the crust! That doesn't count! NO GOOD! NOOO!"

Long Island comedy is wild, crazy, and everyone agrees, is here to stay. "One of the greatest things about comedy is that everybody can be an expert," notes Gary Smith, the owner of The Brokerage. "Everybody knows what they like and 99 times out of 100, they leave satisfied. If you have enough variety, you can have a great show. I love this business because anything goes. Comedy is universal."

The Great Indoors

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1237:]]

New York City has some of the best – and worst –

public spaces in the world.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1227:]]

If, as the German poet Goethe proclaimed, architecture is frozen music, then New York City is the largest – a most discordant – collection of tunes this side of PDQ Bach. That becomes even clearer as cold weather forces New Yorkers indoors more and more – to the lobbies and atriums, train stations and malls that make up so much of the city. Indeed, from the grandeur of Grand Central Terminal to the horrors of Pennsylvania Station, it soon becomes clear that Manhattan has the most extensive collection of great and terrible indoor public spaces in the world.

Many say that public space is a public declaration. “In olden times, people used to go to a church – this incredible building that elevated their spirits out of their everyday environment. What modern architects try to do is elevate the human spirit in the same way,” said architect Gregory Stanford. “Architecture,” said architect Steve Papadatos, “is a reflection of society and the way society thinks.”

If that s the case, what do some of the Big Apple’s indoor spaces say about New York? That it is eclectic, with a sometimes disdainful a sense of its own history and the importance of such spaces: Why else would it allow the original Penn Station bite the dust? But also that it is rich in beauty, diversity, and the unusual? Where else would you find beautiful spaces serving such diverse functions: Radio City Music Hall for concerts, the Morgan Library at 36th Street for reading, the New School lobby at 12th street for education?

"Good public space makes people feel welcome, secure, and helps them interact with other people,” said Tony Hiss, a longtime writer for the New Yorker and author of The Experience of Place. "They can also be places that are exciting to be in, stimulating, and nourishing to the eyes and ears and the other senses. They are places that speak to every one.’’

That said, what are the indoor public spaces that "speak" most favorably to New Yorkers? In an informal survey, architects, designers, and critics were asked to pick the best spaces, the worst spaces, and the spaces that no longer exist but are missed the most. The choices to top all three lists were train stations: Grand Central Terminal was cited as the best, Penn Station as the worst, and the old Penn Station as the most missed.

Everyone had eclectic choices. Architect Jonathan Friedman pointed to the subdeck of the aircraft carrier Intrepid, now part of a national museum at the west end of 42nd Street, as a "missed space," saying, "when it was part of a ship, it was a huge, enclosed open space, but now they've divided it into little rooms." Urban planner Tom Thomas fondly recalled McSorley’s Ale House – “before women were allowed in. The whole atmosphere has changed.”

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1228:]]

Some cited subway cars as the worst spaces, with architect Joel Ergas remarking: "They are so functional they're dehumanizing, especially when compared to other cities. There isn't even a nice piece of advertising to look at. I don’t want to look at ads for torn earlobes.”

There were frequently mentioned spaces that didn't fit the criteria of "indoor," such as the now-closed observation deck at the GE Building. “In a way, it was the most exciting deck in the city,” Hiss said. “Unlike the Empire State Building, where you're peering into Olympian distances, here you're at eye level with the tops of skyscrapers. It made New York feel like an intimate living room.”

Many chose spaces that were not architecturally grand, but had a sense of people, such as the New York Stock Exchange (designer Tom Geismar called it "a great show, so big and so lively, with people running around, gesturing and paper strewn all over the place), or the old Thalia, long-gone from its spot on 95th Street and Broadway (Ergas called it as "funky and wonderfully inconvenient. I remember the floors were so filthy if you dropped something, you didn't dare pick it up.")

Others were bothered by current building spaces "What disturbs me the most is that so - much of the recent work has been mediocre, so off-the-rack and not built with New York in mind or its people in mind," Hiss said.

But all felt that there was a new sense about public space that offered hopeful signs for the future. "People are now more aware of the value of spaces and their uses," Hiss said, "and I think they realize they have to work to keep them there. If they simply leave it to the whims of developers, they may lose them. It goes beyond bricks – it's about what makes a city a desirable place to be in. The function of a city is that it helps you grow up."

"I hate multiplex theaters," Ergas said. "You're herded like cattle, faced with the smell of artificial popcorn butter, and they're not even interesting spaces to wait in. You may as well be walking into a factory."

"A great place should involve all your senses," observed urban planner Thomas. "A great space is not about just sitting and viewing. It is about moving, smelling, and hearing. It's about living."

Here are spaces that many experts loved, hated or missed.

THE MOST MEMORABLE

Grand Central Terminal, 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue. Constructed between 1903 and1913, this Beaux Arts structure features a 12-story ceiling in the main concourse, three huge windows separated by majestic columns, and a Beaux Arts clock. "To walk into it is to feel the excitement of going away," said architect David Beer. It makes leaving on a trip an occasion."

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1229:]]

Citicorp Center, 53rd Street and Lexington Avenue. The skyscraper's enclosed, three-level atrium, lined with restaurants, fast-food outlets and shops, was cited by architect Gregory Stanford because "it is a visually interactive space that is conducive to people. There is a lot happening there, but it keeps a human scale. The fact that they have a skylight gives you really terrific natural light-It is"like a wonderful indoor town square."

30 Rockefeller Plaza lobby, 49th·50th Street and Sixth Avenue. Still known to die-hard New Yorkers as the RCA Building, the 70-story GE Building houses NBC Television and is one of the finest examples of office space in the city. "Going to an office is not as much as an occasion as going for drinks at a restaurant or traveling to Montreal," Beer noted, "but it is an everyday event, so it's nice to go to a place that's uplifting." Architect James Nichols agreed: "Spaces like that are real temples to industry, and have the old-time graciousness of the workplace. The materials are fantastic; the elevators are phenomenal. That was an era when office buildings were· competitive and developers really tried to outdo each other with swankier lobbies."

New York Public Library Exhibition Hall, 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue. This was a "lost" space restored in the past decade. The Great Exhibition Hall in the main library had been chopped up into offices with dropped ceilings, but has been returned to its full grandeur. "It is stunning," Hiss said. "There are richly beautiful wood columns and paneling, wonderful light coming into it and it is so, so elegant. You feel like you're in a private club for everybody, and what it says is there's nothing more important you could be doing than reading a book."

IBM Garden Plaza, 56th Street and Madison Avenue. Growing out of the lower floors of the green-granite IBM Building, this garden features grown bamboo trees, flowers, comfortable chairs and marble tables. "You're part of New York in this wonderful glass atrium," architect Papadatos said. "You're in the middle of Midtown and in a park. You can sit there and forget the hustle and bustle of city."

THE MOST HORRIBLE

Pennsylvania Station, 34th Street and Eighth Avenue. New York's other main train station is loathed by all, for itself and for what it replaced: a grander, demolished station. "This place is a disaster," Ergas said. "It's the railroad entry into New York and it could be Podunk for all the feeling it has of New York." Beer called it an "extension of the subway" while Thomas said that it is "short, squat, and totally unattractive for every use. It's a place you want to get through quick, whereas in the old one, you could turn around 360 degrees, looking at it and stand in awe for an hour."

AT&T Building pedestrian plaza, 55th Street and Madison Avenue. Called the first post-modern skyscraper, this Philip Johnson-designed building has a darkly forbidding, wind-swept plaza. "It is cold and dark, too high and too cold," said Stanford. "There is a lot of granite. Johnson wanted to create a monument to AT&T. It is a monument. It is incredibly grand, but it doesn’t relate to human scale." Partly in response to complaints such as this, Sony Corp. of America, which has taken over the lease on the building, plans to renovate the plaza.

World Trade Center lobbies, 1 and 2, World Trade Center, Church Street. A 16-acre complex, with New York's two tallest buildings, the center also has what some call the city's ugliest lobbies. "Something like that is very bad because it is very impersonal, and very, very high," Papadatos noted. "It makes you feel like you're nobody."

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1230:]]

Seventh Avenue IRT subway elevator, 191st Street stop. The lowest point in the subway system, under the bedrock of Washington Heights, this station requires an elevator to exit. As a public space visited by thousands every day, the elevator offers, in Hiss' words, "the most endless feeling and the most dispiriting ride anywhere. It's not that you feel unsafe, it's just what you imagine the elevator that takes you to Purgatory would be like."

Trump Tower, 56th Street at Fifth Avenue. The 68-story glass building with apartments and shops features a six-story atrium paneled in pinkish orange marble and trimmed with high-gloss brass. Most agreed it is a spectacular ode to tackiness. "I think it's pretty horrible," Stanford said. "It's very glitzy and people either love it or hate it." "Some malls are fine in themselves," Beer said, "but vitality of the streets."

THE MOST MISSED

Pennsylvania Station, 34th Street and Eighth Avenue. Demolished in 1963, the old Penn Station is cited by Hiss "as three of the greatest places in New York. There was the Great Concourse, a huge room modeled on the baths of the Roman emperor Caligula. There was a vaulted stone space behind it, an equally remarkable stone shed of arched steel and glass. And then the Savarin restaurant, even more extraordinary. The loss of all that had a lot to do with the blighting of that area."

Chrysler Building restaurant, 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue. Stanford called this Art Deco space, a restaurant in the 1940s, "one of the greatest places in the city. The detail, the beauty - it was remarkable."

CIty Hall subway station, Lexington Avenue IRT. To Hiss, this station, at the end of the Lexington Avenue line and closed years ago, was "the greatest of all subway stations, with great tiling, beautiful paneling." Trains still rumble through it, since it is used as a loop to turn downtown trains uptown, but only motormen get to see this beauty.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1231:]]

Fast food at Horn & Hardart. Horn & Hardart Automats, throughout the city. A chain of self-service restaurants featuring marble counters and Art Deco ornamentation, the Horn & Hardart automats were seen in Woody Allen's movie "Radio Days," and are fondly recalled by Ergas. "They were beautiful, interesting and exciting. They had marble and brass and beautiful metals, and were efficient in a more human way than the fast-food restaurants of today."

Biltmore Hotel lobby, 43rd Street and Madison Avenue. Torn down and replaced by the Bank of America, the Biltmore had an elegant, posh lobby, which featured a large clock that, Thomas said, "you always met your date under. It was a classy old New York hotel, with a lot of wood."

And Elsewhere

HERE ARE MEMORABLE indoor spaces outside of Manhattan, too. Among them: the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City,which architect Jonathan Friedman called "nicely flowing, very memorable"; the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens greenhouses; and the indoor food market on Arthur Avenue in the Bronx. "That's one of the liveliest food places I've seen in the world," Tom Thomas said. "It's memorable for the smells, sounds, activity. It's like a European indoor market."

On Long Island, architects praise the EAB Plaza office complex in Uniondale for its indoor garden, atrium and skating rink, which they say encourage people to mingle. Among the places most missed: the Loews King Theater in Flatbush, Brooklyn, and the retail spaces under the Queensborough Bridge –"They're sort of Romanesque in form," Thomas said. "They're glassed in now and the glass is dirty, but if you see them, they're fantastic. Someone should do something with them."

NEWSDAY, January 16, 1993/By TOM SOTER

Women in Construction

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1367:]]

Becoming a Presence

Minorities and women battle for a place in city's construction biz

WHEN SANDRA WILKIN began working as a general contractor 12 years ago, she discovered that the New York City construction business was a man's world. "I'd hear all sorts of derisive comments from men," said Wilkin, president of Bradford Construction in Manhattan. Those comments had nothing to do with her work and everything to do with her gender. "These old-timers would say women don't necessarily belong in this kind of business or they can't handle the kind of things that men can handle."

It is still a man's world. "This is one of the last bastions of male-dominated industry," said Olivia Fussell, president of Manhattan-based Fussell 'Construction. But women and minority contractors are becoming more visible. Many have benefited from membership in the Regional Alliances for Small Contractors, created to help women and minorities gain an edge in an industry that has traditionally been hostile to them.

Take Desmond Emanuel. In the 1970s, the West Indian-born Emanuel worked at an architectural firm that designed such high-profile projects as museums and university buildings. But he felt he had hit a dead end. "I realized the way the architectural profession is structured, it would be limiting for me," he said. "I talked to many African-American architects, and they were always struggling and barely paying the bills. Frankly, I didn't want to spend my professional life that way."

Emanuel went back to his roots and started his own business. "I came from a family of builders," he said. "My father had done historic restorations, and I had pleasant memories of working with him on dock sites." It didn't hurt that he also had a degree in civil engineering.

He opened Santa Fe Construction 11 years ago. In the last 36 months, the Manhattan-based company has seen growth in a SOur economy, expanding from 8 employees to 39. It recently started work on a $7.5- million drug rehabilitation facility in Queens.

Emanuel, Fussell, and Wilkin all have ties to the 3- year-old alliance, organized by major construction firms and public development agencies such as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The alliance is designed to help minority- and women-owned construction companies win public and private contracts, provide a boost to the sagging construction industry and help satisfy public-sector minority and female hiring goals.

The three contractors all believe that the number of women and minorities in the business is growing. Mark Quinn, executive director of the alliance, said he doesn't have statistics 'out believes that the number of women and minority contractors has increased in the last couple of years, and "the alliance is definitely helping minorities and women get business, without a doubt." He said downsizing by large contractors has created opportunities for specialty work by small firms.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1368:]]

Still, a recent report by the city's Human Rights Commission found that only 1 percent of the city's unionized construction work force were women, and 19 percent were blacks, Hispanics or Asians. The report charged that minorities and women still face widespread discrimination in trade unions.

The alliance, which has 3,000 members, offers regular seminars on such subjects as .construction contract law, cost control and computerized planning. It also provides financial assistance. Perhaps more importantly, the organization provides bridges between small firms and more established ones.

"Critical to setting up a business are the relationships you develop,” Emanuel said. One o£ the critical things that is often missing in advocacy programs is the forging of long-lasting and honest relationships. A business succeeds or fails on those. In many instances, those are more important than money in the bank."

He pointed to a job he had when he was just starting out. Although the work was not in the city, he brought his regular crew with him - which prompted a shutdown by the local union. "There are always labor jurisdictional problems," he explained. "Every union local likes to have a certain percentage of local workers on the job. A contractor might want to use his own forces, but that presents a conflict. You have to negotiate. And as a newcomer at the time, with no relationships to speak of in the industry or the union, I had no flexibility. It cost me. So I learned the hard way."

Being part of the alliance - Emanuel is co-chairman of the opportunities committee - has given him more clout. So has hobnobbing with representatives at larger firms who speak at the alliance seminars. "The alliance helps to give you standing," he said. "It helps to build some of that relationship."

The alliance provides financial aid through its Financing Small Contractors Program. Under that program, Citibank provides nonrevolving lines of credit of up to $200,000. Twenty-four loans totaling $6.6 million have been approved for women and minority contractors since the program began. Santa Fe's first line of credit, with Citibank, was facilitated by the alliance.

In addition, the alliance provides free consulting through the Loaned Executive Asaistance Program. Fifty-eight construction professionals address management and operational problems, helping small companies improve their abilities to obtain and manage construction contracts effectively. (For information on the alliance, call 212-435-6185.)

Despite the alliance's help, finding work is stil1 an uphill struggle for most small construction firms. Fussell noted that sexism is pervasive. On a recent job, Fussell's female site manager complained that the client's engineer would not talk to. her as an equal. "The guy was in his late 50s or early 60s and would hardly recognize the fact that she was in charge," Fussell said. If it had been a movie, it would have been a farce: Instead of speaking to the woman, the client engineer addressed all of his remarks to Fussell's engineer, a fiftyish man who had been in the business for decades.

"That's very common," Fussell said. "These oldtimers make it perfectly clear that they don't want to do business with you. So instead of fighting it, I slot in an on-site old-timer who's been around for years. I don't think it's necessary to be confrontational about it. We try to clear our way around any kind of small-minded, petty-minded, chauvinist behavior. It's there. But we always try to keep it quiet and work around it."

If women are a minority in the field, as a foreign-born woman, Fussell is a minority's minority: born in England, with a bachelor's degree in architecture and a master's degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Her small company started with a $75,000 renovation job and is now bidding on projects valued at more than $5 million.

"I enjoy the business," she said. "I think I have the personality to be able to take risks, and this is a risky business. You have to really know what you're doing. But it's a lot easier here than in England. It's such a very strong old boys' network in Britain."

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1369:]]

Chauvinism affects jobs in other ways. Wilkin said that as a woman and small-business owner, she is held to a higher standard than men or larger businesses and also allowed less room for mistakes. "Many times, I am so frustrated, " she said. "I get a headache. my palms sweat. and J say. 'I'll just go into another business.' You just have to do the best that you can with the job to prove that your company's capable and you're capable of doing the work."

Fussell agreed that the pressures and impec:tations were greater: "They (men] are on ·the lookout. They're ready and waiting for US to make a mistake; you're under a microscope. I get the feeling that the old-boy network, very broadly.speaking, is waiting for you to fail."

Fussell contended that the old-boy network.Qften un-, dercuts public-sector hiring goals for Minorities and women. "We recently came across a situation where we had submitted a price of $5 million (for J quite a big , job" that had hiring quotas regarding women, she said, It turned out that the prime .contractor who won the bid wasn't really a woman-owned business, "When you unpeeled the onion, you found that they were a front" for a larger, male-owned company,

Emanuel noted that as a less-established, minority-owned business, Santa Fe Construction'is often not considered for some jobs despite his firm's track record - construction manager for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, and partner on the construction of Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn. "We are still not being invited to the table on the private side to compete against firms which have been around for 30 or 40 years, Today, they don't have the talent we have, but they have the name."

All three contractors said that to succeed in a sometimes hostile environment means working long hours - Wilkin drives to Manhattan from New Jersey and works 16-hour days - and offering a variety of services. For example, Fussell provides general contracting and architectural consulting and is seeking construction management work. "The companies most devastated by the real estate downturn have been those that have been highly dependent on one building type. You have to be flexible," she said.

Conversely, having a specialty can also help. Wilkin began contracting a dozen years ago after training as a nurse and working in health care administration and medical leasing. "Since I had leased space to doctors, I realized there was a need within the healthcare industry for knowing how to build the kind of construction needed by doctors and hospitals," she said. "You need to know about patient flow, corridor areas, about the different requirements for heating and ventilation. It's different from a typical commercial tenant, So I developed an expertise in health-care construction. "

"Today the most challenging thing is to find the right people to work for me," Emanuel observed, "I feel that many individuals today, minority or otherwise, do not have the work ethic, Our success is not because we are a minority-owned company but because we have talent, we work hard, and, above all, we know how to create opportunity rather than just wait for it, I think that is crucial to any sort of success."

NEWSDAY, JANUARY 8, 1994

The Attic

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1232:]]

TALES FROM THE ATTIC

from NEWSDAY, NOVEMBER 1995

When Peter Caranicas moved into his new house, a rambling 1870s Victorian mansion in Patchogue, the neighbors gave him one warning: don’t go in the attic. “They said it was haunted,” Caranicas recalled. “They said that at certain times of night, you could hear a ghost moving about.” Scoffing at the legend – which claimed a young child had been left there to die and could still be heard crying – Caranicas moved in. The attic was big and rambling, 60 feet long, perfect for storage since the building had no basement, and it had a lovely view of the Great South Bay and Fire Island. And, oh yes, there was that ghost. “I don’t really believe in such things,” Caranicas said. “But I did hear noises. It was late at night, and it sounded like someone walking around up there, breathing heavily. I guess it could have been the house settling.” He laughed. “I never went up to find out.”

Attics. They’re dark, they’re creepy, and the stuff of ghost stories. More importantly, for many homeowners, they are an important source of extra space. “I store luggage, old files, memorabilia, tax returns, and the kid’s old art projects, all the things I don’t need ready access to,” said Steve Greenbaum, a manager with Mark Greenberg Real Estate in Port Washington who owns a split-level house in Woodmere. “It’s a very useful space to have.”

Yet if attics are not properly designed and cared for, they can also be a cause of costly problems, from energy leaks to pest infestation. According to Hal Byer of Magic Exterminators in Port Washington, attic invasions by nesting squirrels, raccoons, and bees are a very common problem throughout Long Island. “Pests can create all sorts of damage up there,” he said. “Bees, for instance, can get into the air conditioning duct and come down into the living area. Or the pests can start eating through the ceiling and cause structural damage.”

Experts suggest that homeowners perform a thorough inspection of their attic.The first step should be to check that it is properly insulated. Fiberglass insulation prevents heat from rising out of the house into the attic area. Without that barrier, the dry air of the house will meet the damp air of the attic and create condensation, which can ruin the ceilings in the areas below. Costs of insulation materials vary, depending on thickness and quantity, but prices run from about $12 to $20 a square foot. You should insulate but you should also be sure the attic space has adequate ventilation that allows outside air to circulate.

Engineer Kurt Rosenbaum of KRA Associates in Nanuet, N.Y., said that attics “should never be closed up tight. They can either get too hot or too cold. There must be some vents or the plywood upon which the roof is built can rot.” “I’ve seen roofs where it gets hot up there and the roof warps,” said Roger Migne of RLM Construction, a general contractor based in Massapequa. “You want to keep the hear flowing so you avoid that.”

Alvin Wasserman, a homeowner in Roslyn Heights and managing agent at Fairfield Properties in Commack, noted that “having roof vents in the attic allows warm air to rise out. By keeping the air fresh, the roof and attic are protected and last longer. One thing that destroys a roof faster than anything is when the underlying plywood gets moist and is not allowed to dry out. The roof begins to sag. Those problems could cut the roof’s life in half.”

Besides vents, some suggest employing an attic fan. Tied to a thermostat, the fan switches on when the area hits a predetermined temperature. “That keeps it cooler up there,” Greenbaum said. “You can also put in a fan that sucks air out of the house. It can save on air conditioning costs.” Prices on such equipment range from $200 to $600.

Attics can also be a source of pests – and not just the ghostly kind. Besides spirits, Caranicas recalled a raccoon problem that he fought by putting mothballs in the animals’ nest, hoping to drive them away. “But they just took them out, one by one,” he said. “They are very smart.” Greenbaum’s neighbor had a squirrel invasion which took eight months to resolve. “If a squirrel can get in, he will nest in the attic and have babies,” Wasserman noted. “And a squirrel will chew his way through almost anything,” including air conditioning and electrical wiring.

Many homeowners have problems because they try to remove the animals themselves instead of spending a few hundred dollars on professionals. One difficulty for the novice is the complexity of trapping not killing. It is illegal to poison squirrels and raccoons, so the animals must be either driven away or trapped. That is a time-consuming craft. Experts will come in with special traps, baited with peanut butter for squirrels, marshmallows for raccoons.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1235:]]

“You never use fish bait because that catches cats,” said Steve Menoudakos of Busy Bee Pest Control in Flushing. “We tend the traps daily, and remove to animals, usually to wildlife centers. If they are released in the wild, Menoudakos added, “squirrels have to be carried seven miles away. They have an innate sense of navigation, a homing instinct, like a sailor at sea. They go to the highest point, like an oak tree, and navigate their way back to the nest. So to keep them away from your home, squirrels have to be taken good distance away.” Attics are also sources for birds and bees. Menoudakos has removed many bee hives that were located within the walls and relocated the insects to a bee farm.

Besides trapping them, the professionals will also find how the pests are getting in, usually through unscreened vents, the facia board, the chimney, or other structural openings. A sure sign that you have trouble, Menoudakos said, is the sounds of “scratching, running, scurrying, and thumping. Raccoons will coo like pigeons; they will chirp at one another.” Attics should be inspected regularly – at least twice yearly – for any problems.

Greenbaum said he looks over his space more frequently because, “small leaks can go undetected.The insulation might absorb a leak before it penetrates the ceiling of the room below the attic. If you don’t inspect, by the time you notice the leak, it may have gone through the roof, tile, and roofing membrane, and you can then be into some real costly repairs.” If your attic is in good shape, it can be a more effective area for storage or even living space.

Some suggest improving access. Mordy Lahasky, a homeowner in Woodmere, spent $200 to have his attic entrance moved from the linen closet to the hallway. “I keep a lot of things up there and it’s a lot easier to get them now,” he said. Others recommend remodeling the space into living quarters, if there is enough room, since a well-insulated and designed attic area can add value. “It seems to be a big feature for people,” said Joe Tanna, a broker with ERA Premier Homes in Freeport, who also worked in Queens for years. “If it’s renovated, it makes the house more saleable – even if it’s just having flooring down or a pulldown staircase instead of a ladder.”

According to Adding Space Without Adding On, by Herb Hughes, to do that you need at least seven feet of headroom. Otherwise, the area will appear cramped and uncomfortable. “When I was looking for a house, the idea of an attic sounded good but what ultimately turned me off was they were inaccessible and unfinished,” said Abbie Fink, a homeowner who eventually bought a house in Westchester. “We saw finished attics with playrooms, and that had more possibilities. They were great. I think that’s more attractive than using for storage.”

Tanna noted that in Queens and Freeport, attic living spaces are “very desirable. Most of the homes there are three-bedrooms, bought by first-time home buyers and immigrants who have larger families. Providing it has the proper heating, space, and permits from local authorities, an attic can be an ideal living area.”

Some have found even more unusual uses for their attic – and have even eliminated “ghosts” in the process. When Wasserman bought his house, the TV antenna was mounted on the roof attached to the chimney. It was subject to the elements, and during a big storm, was even blown off. Reception was not good, sometimes included double, or ghosted, images. Then Wasserman had an idea. “I took the antenna down and brought it into the attic. Using insulated wire, I suspended it up there, pointing it in the right direction. So now the wires aren’t whipped around by the wind. You know, the reception is great. In fact, I think it’s better than it was before.”

Upstairs Downstairs

The Continuing

Appeal of

UPSTAIRS

DOWNSTAIRS

By TOM SOTER

for THE NEW YORK TIMES, 1999

It has been 29 years since the early 20th century costume drama, “Upstairs Downstairs,” premiered on British television. And, by all rights, it should be as forgotten today as the creakiest of kinescopes. Shot on videotape and generally confined to indoor sets, it has long since been surpassed in production values by such sweeping mini-series as “Tom Jones” and “Vanity Fair.” And, unlike many of today’s fast-paced melodramas, the series was defiantly leisurely in its approach – favoring long takes and silent reaction shots – and positively mundane in its concerns: should a butler serve the master’s best claret to a secretary or not?

Yet “Upstairs Downstairs” made the mundane memorable, the leisurely luxurious. And, these days, it is positively thriving. In 1999, A&E Home Video began releasing the entire 68-episode series on video, including a number of episodes not generally telecast (the first three seasons are in stores now; the last two will be coming out later in the year). There is also an “Upstairs Downstairs” web site featuring commentary, notes, and trivia; a television documentary came out in 1996, and at least two books about the series are in the works. The term “Upstairs Downstairs” has even entered the critical lexicon. When a recent British import, “Berkeley Square,” appeared here, critics – without any further explanation – labeled it “Upstairs Downstairs”-like (it wasn’t).