Television Shows

I Spy

WONDERFULNESS

By TOM SOTER

from VIDEO, 1993

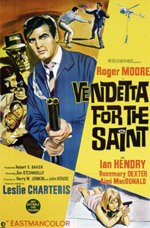

I Spy

1965/1966. Robert Culp, Bill Cosby, Gene Hackman, Carroll O'Connor; dir. Richard Sarafian, Earl Bellamy, Robert Butler. Two tapes, 100 min. each; $19.95 each. United American Video.

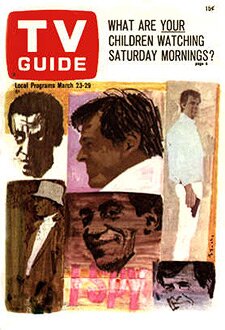

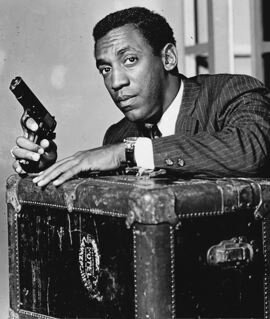

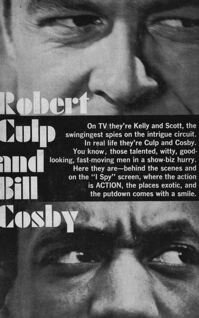

Long before Dr. Cliff Huxtable and those Jello commercials made Bill Cosby a multi-millionaire, he was appearing as Alexander Scott, partner to Kelly Robinson (Robert Culp) in the groundbreaking spy series I Spy. The show, about two globe-trotting CIA men, is unique among the 1960s crop of James Bond TV clones: it was actually filmed in the foreign locations the agents visited and it paired a black and a white man as equal partners.

Besides that, the series is appealing for its fast-paced action and clever stories, and the easy rapport and insolent cool of Culp and Cosby, who often improvised their rambling exchanges. "Life is good," says Culp in one. "It's better than that, man," replies Cosby. "On a day like today there's a wonderfulness from the sky and the sea and the people that kisses you all over the neck and nose." Culp: "Name another day when such a report to the Pentagon was written by two fine American spies."

The four episodes represented here, primarily from the series' first season, are hardly representative of the show's humor and clever plotting or even its globe-hopping, since three take place in Mexico. Nonetheless, there is intrigue, beautiful photography, the snazzy I Spy theme tune, and the chance – in "It's All Done With Mirrors" – to see Archie Bunker (Carroll O'Connor) as a Communist agent. Now that's a trip, man.

The tapes are available by mail order from United American Video (803-548-7300), which has also released classic TV episodes of Hill Street Blues, Lou Grant, The White Shadow, and The MaryTyler Moore Show.

NOTES FOR AN ARTICLE

I would often write a longer version of the published article and then cut it down. Here are my notes to the review shown above. Some of the material was drawn from an earlier article I had written about TV spies in 1984.

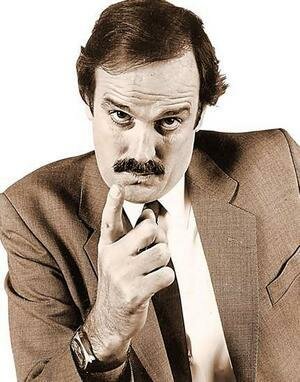

Bill Cosby

Bill Cosby

Part spy story, part travelogue, I Spy is unique among the 1960s crop of James Bond TV clones for a number of reasons: unlike The Man from U.N.C.L.E. or Secret Agent, the series actually filmed its episodes in the exotic locations the heroes visited (not a redressed back lot). That gave the show a picturesque quality that was complemented by the other unique aspect: the first-time TV pairing of a black man and a white man as equal partners. As the duo – two CIA agents masquerading as a tennis star and his trainer – Robert Culp and Bill Cosby have a charming, improvisational rapport that makes them the height of cool.

The four episodes represented on these two tapes come primarily from the series' first season – and are hardly representative of the show's smart–aleck humor and clever plotting, or even its globe-hopping, since three of the four shows take place in Mexico.

A landmark for its use of a black man as a co-star, the show featured Robert Culp as Kelly Robinson, an international tennis champion, and Bill Cosby as Alexander Scott, his trainer. The two men roam the world playing tennis – but are really agents on

missions for the CIA.

Besides being a well-produced travelogue (shot on location), the show is fun for its characterizations. Robinson and Scott have amusing exchanges on everything from Scotty's boyhood in Philadelphia to Robinson's feelings about life in the spy business; they have a nice camaraderie that seems real.

"Life is good," says Culp in one exchange.

"It's better than that, man," replies Cosby. "On a day like today there's a wonderfulness from the sky and the sea and the people that kisses you all over the neck and nose."

Culp: "Name another day when such a report to the Pentagon was written by two fine American spies."

But the overall tone of the show is serious. Humor worked in between the cracks, as Robinson and Scott defuse tense situations with jokes. Scott is a Rhodes Scholar who speaks many languages (one of the realistic touches of the series is having foreigners speaking their own languages to each other, not accented English as some series preferred). Robinson is intelligent, athletic, and laid back. Culp and Cosby play their roles with an insolent cool, which they drop as soon as action beckons. For the duo, demeanor is a mask. Spying is necessary, but dangerous. The only way to do it is by keeping a humorous perspective, depending on their wits and their friendship.

"Prejudice is based on ignorance," Cosby noted in 1967. "Many people have preconceived ideas about Negroes. On I Spy, they've seen I'm an everyman. The fact that I'm colored is as relevant to the role as being fat, tall, or pock–marked might The Avengers≤ I Spy helped break discriminatory barriers by ignoring them. Cosby won three Emmy Awards for his performance.

The series is a story of companionship, quite unlike the Bond movies in that respect. It underlines the need for working together to solve unpleasant problems. "Kelly and Scott are equals," said Ed Goodgold, who wrote a study of the series. "If a silly question has to be asked or a silly mistake made, both are capable of making it. Neither member of the team is infallible."

The series' best qualities are encapsulated in "Home to Judgement," a third season episode which finds the agents hiding out at Kelly's uncle and aunt's, seeking shelter from a nameless, faceless foe. The episode shows the serious, dangerous quality of the spy's life: humor is not a luxury, it is a defense. The world can be ugly.

This realism is emphasized by Fouad Said's inventive photography, which often has a handheld, cinema verite look. Fights are violent, jarring, with closeups, quick cutting, and often no music. Even the opening credits come on suddenly, without the normal three©second pause between pre-credits sequence and titles. You are thrust into the story much as the spy is thrust into a mission. It gives the series a kinetic, frenzied realism from the beginning, counterpointed by the low-key Culp and Cosby.

The best is probably "Happy Birthday, Everybody," which features Gene Hackman as a lunatic demolitions expert and Jim (Mr. Magoo) Backus as his target. There's also "It's All Done With Mirrors," which finds Carroll (Archie Bunker) O'Connor as a communist expert in brainwashing.

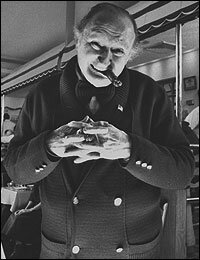

John Cleese

Cleese: adman, madmanVIDEO ARTS

Cleese: adman, madmanVIDEO ARTS

By TOM SOTER

from VIDEO, 1992

Fans of John Cleese's exasperated, know-nothing Basil Fawlty in the 12-episode TV Classic Fawlty Towers, take note: Basil lives! (Well, sort of). In the 1970s TV series (available on video from CBS/Fox), Cleese perfected the pompously inept hotel keeper who never got anything right. Salt in the sugar shakers, corpses in the kitchen, rudeness to the guests – you name it, Basil did it.

Cleese has learned from Fawlty's mistakes and profited handsomely in the process. In 1972, he and four partners founded Video Arts, a British-based company designed to produce humorous corporate training films. And in the last 20 years, it has done just that, creating more than 125 half-hour programs that have

been used by 110,000 organizations throughout the world. As of September 1991, worldwide sales (to AT&T, Hyatt Hotels, Federal Express, and General Electric, among others) were in excess of $26 million.

The videos (available for rental or sale from Video Arts, 8614 W. Catalpa Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60656; 1©-800-553-0091) take advantage of Cleese's reputation and comedic skills. He is often found in some very Fawltyesque situations: as a rude hotel staff member who learns about courtesy from the Patron Saint of Hospitality; as an inefficient board chairman who dreams he is hauled before a court for the negligent conduct of meetings; as a boss unable to deliver bad news; and as Charlie Jenkins, a master in the art of unselling products ("Who sold you this, then?" he remarks to a customer, undoing months of hard, patient selling). The videos, prepared with the help of management consultants, offer the dos and don'ts of the various topics (customer relations, running a company, seeking advice) and are accompanied by detailed training booklets.

¡

By his own admission, Cleese, a former member of Monty Python's Flying Circus and co-writer/star of A Fish Called Wanda, began the company to make a quick buck but later stuck with it because the topics interested him. Humor was always key. "The right way to use comedy is to make sure that all the humor arises out of the teaching points themselves," notes the comedian. "Every time the audience laughs, they're taking a point. And if they remember the joke, they've remembered the training point."

He must be doing something right: Video Arts has won more than 200 awards, including the National Educational Film & Video Festival's Gold Apple. To business folk, however, the real sign of VA's success would probably be its 1989 sale to an outside conglomerate. Basil Fawltys of the world, take note.

Munsters Eatery

MEAL WITH A MUNSTER

MEAL WITH A MUNSTER

By TOM SOTER

from VIDEO, 1991

To some, typecasting and old age can be a road block. Not for Al Lewis. Four years ago, the erstwhile actor, now 81 and best known as Grampa on the 26-year-old TV series The Munsters, began a new career as the owner of a New York City restaurant called – what else? – Grampa's. Although the menu of pasta, fish, and chicken (no red meat) is for the health conscious, the eatery's initial appeal is for Munsters fans. Lewis says 99 percent of the first-timers come because of the TV connection but return for the food.

"I'm beyond famous, I'm a cult," remarks Lewis, who notes that the show is still seen in 44 countries. The actor plans to franchise his restaurant in Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago, but scoffs at suggestions that this is a new turn in his career. "What's the difference between selling a ticket for a show and selling a ticket for a restaurant? If people like the show, they applaud and tell friends. If they like the food, it's the same thing. They come back." Can an Addams Family catering service be far behind?

Sci-fi TV

ASTOUNDING TALES

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 1996

An intrepid, multi-racial crew goes where no one has gone before, exploring the deepest reaches of space. A scientist creates life but gets more than he bargained for when his creations turn against him. A pair of detectives investigate murders of psychics, using a psychic to help them. Earthlings battle aliens in space, where no one can hear you scream.

If it all sounds new and different, yet somehow vaguely familiar, welcome to age of Science-Fiction and Fantasy television. It’s 1996, and the weird and unusual has invaded the tube: a new “Outer Limits” is back; the weirdly compelling “X-Files” is entering its third season, graduating from cult to mainstream favorite; and the latest spinoffs of “Star Trek,” “Deep Space Nine” and “Voyager,” are zooming through broadcast space. Those shows are not alone, either: the fantastic in television is growing more normal every day, with such series as “Babylon Five,” “SeaQuest,” “Nowhere Man,” “Deadly Games,” “Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman,” and “Space: Above and Beyond.” There's even a Sci-Fi cable network, featuring such golden oldies as “Twilight Zone,” “The Prisoner,” and “The Time Tunnel” (not to mention news programs and old movies).

Why science fiction and fantasy? Why now? When the original “Star Trek” premiered 30 years ago, it was an industry axiom that the genre of the fantastic was low-rated kid stuff. In fact, early TV sci-fi featured Rod Brown of the Rocket Rangers in silly adventures, and such later entries as “Lost in Space” and “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea” found its heroes battling giant carrots and gun-toting clowns.

“Star Trek” changed all that. Gene Roddenberry’s space opera was the first sci-fi series to feature regular characters facing adult dilemmas. The people were believable, the issues, thinly disguised parables about the times that were a’changing, from the war in Vietnam and race relations to state-sanctioned murder and sexism. “Star Trek,” like the earlier anthology series “Twilight Zone” and “Outer Limits,” used its sci-fi format to disguise controversial, thought-provoking morality plays. And in doing so, the series set the tone for many future programs by proving that fantastic television wasn’t just for kids.

The current television sci-fi and fantasy renaissance, which began with “Star Trek: The Next Generation” in 1987, has presented a range of different series but almost all have two points in common: hi-tech, computer-generated special effects and a mile-long streak of paranoia. The latter is not surprising, either, since part of science fiction’s appeal is the way it uses the future to examine the present.

“If you look at the second season of ‘The X-Files,’ each episode of that season was supposed to be an exploration of our current political predicament,” noted Glen Morgan, a former writer on “The X-Files,” in Cinescape magazine. “Now that the Cold War is allegedly gone, are we creating are own little green men to be afraid of? Are we trying to create villains because we need some level of anxiety?”

Science-fiction is on the upswing because sci-fi acts as a barometer of the public’s basic concerns. Like the original “Star Trek,” which was born in a period of social unrest, these new series are being created in a time of radical political change. Paranoia may be in the air, but so is some of the best, and most adult, science-fiction drama on television.

Even with the success of “Star Trek,” sci-fi and fantasy TV can’t escape the stigma of the “kid’s stuff label.” For every “X-Files” and “Nowhere Man,” there is a “Deadly Games” or “SeaQuest,” aimed at kids. Some more-or-less adult-oriented shows, still make concessions to the youth market, and some are for the adult-as-child. Here’s a quick critical and demographic rundown of some of the more interesting programs:

Adult Head Games

THE X-FILES (Fox)

THE X-FILES (Fox)

Probably the creepiest, scariest, and yet most adult fantasy series on the air, “The X-Files,” a Golden Globe-winner as best drama, tackles weighty issues of trust and respect but also throws in enough subtle scares to shake the most hardened horror buff. The protagonists, special FBI agents Scully (Gillian Anderson) and Mulder (David Ducovny), are troubled seekers of truth, a pair who examine strange deaths and incidents that usually do not have a rational explanation (UFOs, the paranormal, psychic murderers, killers who use lightening bolts). A somber series in which the duo can’t even trust their own bosses to tell them the truth (“Trust No.1” is the password on Mulder’s computer), “X-Files” is made palatable by its low-key, realistic approach and no-nonsense heroes. The program mixes mysticism and the unexplained with grisly deaths and gunplay, fashioning its stories out of a public fascination with the unusual and inexplicable. A recent three-part episode took paranoia to new heights, implying U.S. government complicity in the mass extermination of Jews, genetic engineering, and murder. Some may find it Oliver Stone-ism runamuck, but is it any wonder that the series has struck a chord? With the widespread suspicion of government and government conspiracies, who wouldn’t believe? There may be things we can’t explain, but the popularity of “The X-Files” isn’t one of them.

LOIS & CLARK: THE NEW ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN (ABC)

This version of the 58-year-old super-hero mixes the romantic, slightly camp elements of “Moonlighting” with the action-adventure formula of the old “Superman” series, attempting to give the goings-on a young adult spin. Here, Superman is a 20-something reporter with an on-again, off-again romance with Lois Lane. The emphasis is on their relationship (hence the cutesy title), with adventures and super-villains taking a back seat. Clark and Lois are looking for love and companionship but find that super-powers bring only complication (when Clark proposes to Lois, she’s ticked off at him for lying to her about his secret identity). The two bicker a lot (“Is my being in danger old hat for you?” she complains when he is almost too late in rescuing her) as the program tries to handle the characters and issues realistically and wittily. Lacking the depth and sophistication of “X-Files” or even “Star Trek,” “Lois & Clark” is enjoyable as a free-wheeling romp, part-soap opera, part-action/adventure. Be warned, however: If you’re nostalgic for George Reeves’ straight-fisted heroics, this Superman isn’t for you. But if you want to smile at an interesting take on an old idea, check it out. Your kids will certainly enjoy the silly villains.

STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE (Syndicated)

The third “Star Trek” series is the least interesting one, although you have to give the producers credit for trying something different. Unlike its predecessors, Deep Space is not set aboard a traveling spaceship seeking out new worlds; it all takes place on a space station near a wormhole (a spatial anomaly that transports spaceships millions of miles in a second). If “Star Trek” was “Wagon Train” to the stars, “Deep Space” is “Gunsmoke,” right down to the saloon keeper, friendly doctor, and weird-looking visitors who drop in to cause mischief. The series has tried for personal, character-driven stories, but so far has failed to light the public’s fire. As a result, the fourth season has added Worf (Michael Dorn), the dour Klingon from “Next Generation,” and, if the season opener is any judge, upped the action quota. It’s my least favorite “Star Trek,” partly owing to the relatively dull characters, led off by somber Avery Brooks as Captain Benjamin Sisko. The only bit of life comes from the ill-tempered security guard, an alien shape-shifter named Odo (Rene Auberjonois), who is haunted by his past as he tries to fit into a world he never made. Children may enjoy the cute aliens who drop by for a mug of tranya.

Space Wars, Diverting Kid Stuff

SPACE: ABOVE AND BEYOND (Fox)

Some whiz-bang producers must have been looking at the most popular action flicks of the last few years when they put together this series. A combination of Top Gun and Aliens, with a little Star Wars thrown in, “Space: Above and Beyond” chronicles the adventures of a group of marine cadets in the year 2063 as they engage in space combat with a nasty, unseen alien force that destroyed an unsuspecting earth colony. The stories, a far cry from the shiny world of “Star Trek,” are somber, dimly lit tales of prejudice, fear, and violence, set in a militaristic earth of the future. “Space” uses its sci-fi trappings to touch on contemporary issues like affirmative action and feminism but also doesn’t forget what a war series is about: each episode has at least one flashy space dogfight. The characters, however, are stereotypes, designed to appeal to the teen market, and the series is most interesting when it delves into the gritty side of war. It’s a far cry from the sophistication of the old “Combat!” series, though, which used its war stories to explore human dilemmas. Now that was a great show.

BABYLON FIVE (Syndicated)

Babylon 5, a five-mile-long, United Nations-style space station in the year 2259, is the center of intrigue, aliens, and plenty of action as Captain John Sheridan (Bruce Boxleitner) tries to keep the peace and uncover the roots of a conspiracy against the United Earth government.There are a lot of space battles, the usual multi-racial, multi-gender, and (for sci-fi) multi-species cast, but “Babylon Five” offers nothing particularly new or different, except for how many ideas have been recycled from past movies and series, including Bladerunner, Star Trek, Battlestar Galactica, and Star Wars. Although the show presents a dark take on the future, Boxleitner’s hero is a true-blue action hero, ready to leap into action. Billy Mumy, Will Robinson from “Lost in Space,” co-stars as an alien. Warning! Warning! as the Robot used to say. Adults need not apply.

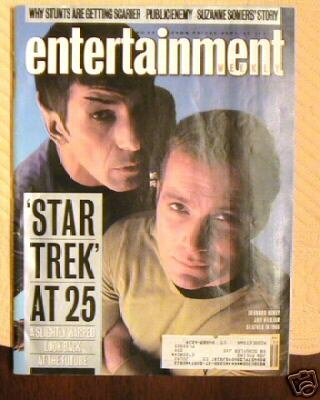

Star Trek

Ten Hours of Star Trek

By TOM SOTER

FROM ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY, September 27, 1991

What is the final frontier for Trekkies? Outside of meeting the entire cast or riding on the Enterprise, it would probably be luxuriating in a marathon of all five big-screen flicks. Thousands got their chance Sept. 7 when Paramount staged a 44-city, one-day screening of the film series. If you missed it, don't despair: Through the miracle of home video, I re-created the experience in the comfort of my home, compiling this viewer's log:

Hours 1-2: Star Trek-The Motion Picture. The crew is reunited in a high-tech edition of the series: Uhura's hair is a red Afro; McCoy has a beard; Kirk and Scotty are slim. The colorful TV uniforms have been replaced by gray leisure suits. The plot, about the godlike V'Ger heading for earth, is the same as for the TV episode ''The Changeling.'' A lot of talk, not much action. Chekov burns his hand and screams. Spock cries.

Hours 3-4: Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Ricardo Montalban reprises his villain role from the TV installment ''Space Seed'' in a Moby Dick-inspired story about obsessive revenge and mid-life crisis. Kirk meets his son, Spock meets his maker, and Chekov has a bug placed in his ear and screams. Uhura's hair is now black and straight, Scotty is starting to lose his battle of the bulge, and the uniforms are red. Kirstie Alley is sexy as Lieutenant Saavik.

Hours 5-6: Star Trek III: The Search for Spock. Kirk & Co. try to revive Spock. In a parody of Star Wars, McCoy goes to an intergalactic bar; Kirk's son is randomly killed; and the Enterprise blows up. Judith Anderson plays a Vulcan priestess, Christopher Lloyd a Klingon who destroys error-prone underlings. Uhura's hair is curly. Scotty, getting bigger. My eyes are bloodshot. Did Chekov scream in this one? How and why did Kirstie Alley turn into the less-sexy Robin Curtis?

Hours 7-8: Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. The movie is about finding whales in the 20th century. Kirk and Spock introduce their Laurel and Hardy act, aided by Catherine Hicks as a marine biologist. Chekov falls off an aircraft carrier and screams. Kirk gets court-martialed. Spock accepts his human half. Uhura's hair is straight again.

Hours 9-10: Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. A Vulcan cult leader (Laurence Luckinbill) searches for God as he cures people's ''emotional pain.'' Shatner directs. He must have been tired. I sure am. Everyone looks aged, especially Uhura, who's now silver-haired and seems attracted to Scotty the whale. Kirk and Spock perfect their Stan & Ollie act. Hey! Kirk and Spock are both captains, aren't they? So who's in charge here? What's that? He's dead, Jim? The engines can't take it anymore? The Vulcan mind meld? (Again?) Omigosh-live long and prosper, everyone, and for pity's sake, beam me up.

Terry Jones

A PYTHON REFLECTS

A PYTHON REFLECTS

By TOM SOTER

from VIDEO, 1991

Monty Python is 22 this year – 22 years since Monty Python's Flying Circus changed TV history with its wacked-out, absurdist humor, from five wacked-out, absurdist Britons and one American from Wisconsin. Monty Python's Flying Circus – following Vols. 1-21, though with Python, you never can tell – has

also just hit the racks, bringing to an end the complete release of the complete televisual works (two episodes per tape, except for the last which has three) of the Python troupe. Also out: a re-release of the group's best film, The Life of Brian, and a live performance at the Hollywood Bowl.

"The Life of Brian was a great experience," remarks ex-Python Terry Jones, now living in a suburb outside of London, writing children's books, directing films like Personal Services and Erik the Viking, and feeding olives to his tiny dog. "We had about two weeks together in a house in Barbados, sort of getting out the shape of it, and it really came out right at the end. I liked it."

Not so Monty Python's Meaning of Life, the sextet's last group effort. "It was very difficult getting everybody together to do Meaning of Life. It was a less happy writing experience, I must say. We're just so different, we couldn't get everybody together, whereas in the past we'd sort of meet, discuss things,go off write for a couple of weeks, come back together again, weed out stuff. We'd spend two or three days together, or a week together, then go off and do it again. So it was all sustained. With Meaning of Life, we'd meet, we'd disappear again, we'd maybe meet up again two months later or something. We just couldn't keep everybody together, and it just went on and on and on. Then we went over to Jamaica to get the script together. It was a disaster. And then, it was the first two days, talking and talking and talking, and trying to get a structure. And it was just hopeless, we just couldn't go anywhere. I remember waking up Wednesday morning with this sinking feeling in my stomach I remembered having during exams, and I thought, Jesus Christ, this isn't working. It's all going to fall to pieces."‘

The Fugitive

David Janssen

David Janssen

A MODERN MORALITY TALE

VIDEO, May 1992

The Fugitive Collectors Anthology 1991 Compilation. Volume 1: "The Girl from Little Egypt" (1965). David Janssen, Barry Morse, Ed Nelson, Pamela Tiffin, Diane Brewster; dir. Vincent McEveety/"The End Is But the Beginning" (1965). Janssen, Morse, Barbara Barrie, Andrew Duggan; dir. Walter Grauman. 104 min. Ten tapes with two episodes each, available through mail order (1-800-333-0113). $24.95 each. Nu Ventures Video Library, 7930 Alabama Avenue, Canoga Park, CA 91304.

Call it a Christian Crime Drama, but don't call The Fugitive a flop. Twenty-nine years ago, Dr. Richard Kimble began running. And when he stopped, on August 29, 1967, the largest TV audience in the world watched him prove his innocence by confronting the man who had killed his wife.

A huge success in its initial "run" (excuse the pun), The Fugitive followed the adventures of Dr. Kimble (David Janssen) as he criss-crossed the country searching for the One-Armed Man who could clear him. It inspired a slew of imitations (The Invaders, Run for Your Life, The Incredible Hulk) and homages (frequent references were made to it on Twin Peaks) but no equal. And no wonder. It was an odd combination of morality and melodrama, cleverly dressed up as an action series.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1353:]]

"The Girl from Little Egypt" sets the pattern for the 119 other episodes: Kimble accidentally gets involved in a sordid drama of infidelity but manages to set a young girl on the right path before fleeing the police. Although thin by Fugitive standards, it does contain footage – via flashbacks – showing how the Kimbles fought, wife Helen died, and the doctor began running. "The End Is But the Beginning," from the second season, explores Lt. Philip Gerard's (Barry Morse) obsession with catching Kimble in a storyline that finds the Fugitive trying to convince the detective he was killed in a truck wreck. Based on Victor Hugo's Les Miserables and the real-life case of falsely accused Dr. Sam Sheppard, The Fugitive succeeds not because of its improbable premise, but because of its acting, writing, and underlying message of hope. The series is a fable of redemption through suffering: in spite of the abuse he receives, despite an uncaring system attempting to crush him, Kimble always returns love for hate, concern for callousness, truth for lies. In a world of "Me Firstism," deceit, hopelessness, and despair, The Fugitive's message is endlessly appealing. It is a modern morality tale – and fun, to boot.

The Fugitive Fan

FUGEFAN

FUGEFAN

By Tom Soter from VIDEO, 1993 To paraphrase George Bernard Shaw, some fans see shows and say "wow," others see them and say, "Why can't I do that?" People like "Texas Bob" Reinhardt of Austin, Texas. He isn't just a fan of the 30-year-old David Janssen video series The Fugitive – he is a follower, a believer, a high-priest at the shrine of the late actor, best known for his role as Dr. Richard Kimble, the man falsely convicted for the murder of his wife. Janssen spent four years hunting the real culprit – a one-armed man – and his role will be reprised this summer in a big-screen version starring Harrison Ford.

Texas Bob got there ahead of Ford, however. Founding a fan club and issuing a newsletter ( The Stafford Chronicle, named for Kimble's mythical home town of Stafford, Indiana) wasn't enough – after all, Rusty Pollard in nearby Garland, Texas, had already started his own "Fuge" newsletter, On the Run. Reinhardt staged a Fugitive convention in Janssen's home town, at which the late actor's mother, Berniece, spoke, and then fulfilled every Fugitive fan's dream: he actually portrayed Dr. Kimble in a half-hour video.

Billed as the "first new episode in 30 years," Texas Bob's "Fear in a Pioneer Village," employs the titles, music, and voiceover narration familiar to fans of the show, as well as its trademark chases and moral dilemmas. Janssen's aunt and uncle appear in small parts, with Reinhardt himself essaying Kimble, imitating the mannerisms Janssen made so distinctive: the nervous glance, the half-smile, the slight hunch.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1343:]]

Reinhardt claims "Fear," which features fellow fan club members in key roles, has been selling well via mail order (one viewer called it "absolutely terrific"), but he is also not surprised: "I think Kimble was one of the last real heroes. He was persecuted for what he didn't do, but helps people in spite of that. There was a high moral and ethical value to the series. Personally, there are no other TV shows I like as much. When The Fugitive went off the air, TV ended for me. I never missed an episode."

"Fear in a Pioneer Village," paired with footage of the first Fugitive convention, is available for $23, including postage, from: Memory Lane Video Services, 511 Stillmeadow, Richardson, Texas 75081. To join The Fugitives, Texas Bob's club, send $12 to 507 B. Bellevue Place, Austin, Texas 78705-3109.

The Lone Ranger

THE LONE RANGER

By TOM SOTER

from ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY MAGAZINE

Hi-yo, Silver: Clayton Moore was that masked man.

Hi-yo, Silver: Clayton Moore was that masked man.

To the strains of Rossini's "William Tell Overture," over images of a masked man riding a majestic white stallion, a narrator breathlessly speaks the words that thrilled a generation: "A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust, and a hearty 'Hi-Yo, Silver! The Lone Ranger rides again!"

The Lone Ranger was a landmark show in two mediums: on radio from 1933-1956, it was so successful that it became the basis for a radio network, while on television from 1949-57, it marked the first bonafide hit for the fledgling American Broadcasting System. No wonder. The program's appeal is as timeless as that of Robin Hood and Zorro, with whom the Ranger had much in common.

The series, which followed the adventures of a former Texas Ranger who wore a mask and battled evil, may have been kid stuff but it was loaded with adult messages: the Ranger was friends with Tonto, a Native American, before it was fashionable; he always shot to wound, never to kill; and he spoke with perfect diction. And, like the heroes of The X-Files, the masked man believed in truth and justice, helping the underdog without asking for anything in return.

The show had its appealingly operatic touches: a silver bullet was the hero's calling card while his mask was meant to strike fear into the hearts of his foes. But the Ranger was modest, too, riding off as soon as the job was done, just as those he had helped would invariably ask, "Who was that masked man?" Who indeed? A true American folk hero.

Sidebar

Years on air: 1949-57 (premiered on radio in January 1933).

Top Nielsen Rating: No. 7 (1950-51). Emmys Won: 0

Ranger for Life: For most of its run, the Ranger was perfectly personified by Clayton Moore, a B-movie actor who found his calling as the masked man. He starred in over 100 episodes, two feature films, and then made a career of appearing at charity events as the character. He was involved in a lawsuit in 1981 when the producers of a new Lone Ranger film tried to get him to stop wearing the mask. He recently published an autobiography, I Was That Masked Man.

Series Firsts: The series was the first to have a Native American play a Native American (Jay Silverheels as Tonto). In an era of live television, the show was one of the first to be filmed.

Ranger Secrets: Tonto's pet phrase for the Ranger, "Kemo-Sabe," was supposedly Indian dialect for "faithful friend." It was actually the name of a summer camp.

Where to Find Him: The Lone Ranger's adventures are now rerun on TVLand.

Classic Touch: The show's theme, the "William Tell Overture," was chosen because the producers of the radio show felt that it was suggestive of a horse galloping.

All in the Family: The Green Hornet radio series was a spinoff of The Lone Ranger. Set in the 1930s, the series featured a masked character and also used a classical tune as its theme ("Flight of the Bumblebee"). The Hornet was a great-nephew of the Ranger.

The Saint

![]()

THE SAINT

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 1996

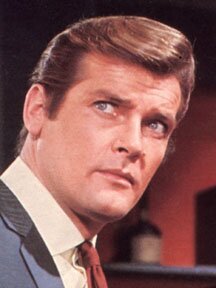

The Saint is a sinner. But The Saint is also a winner. Roger Moore as The Saint, with friends.

Roger Moore as The Saint, with friends.

“Need I explain that you have come to the end of your interesting and adventurous life?” sneers the villain to Simon Templar, a.k.a. The Saint.

Simon twitches an eyebrow, and slides his mouth mockingly sideways. “What – not again?” he sighs.

The villain looks puzzled. “I don’t understand.”

“You haven’t seen so many of these situations through as I have, old horse. I’ve lost count of the number of times that this sort of thing has happened to me. I know the tradition demands it but I think they might give us a rest sometimes. What’s the program this time – do you sew me up in the bath and light the geyser, or am I run through the mangle and buried under the billiard table? Or can you think of something really original?”

The scene is from the book The Saint vs Scotland Yard (1931) and the hero in peril is Simon Templar, the man with the crooked halo who forever transformed the way audiences look at heroes and villains. Self-mocking, suave, with his own moral code, Templar, like his spiritual descendant James Bond, is among the first of the flamboyant fictional anti-heroes who could nonchalantly walk into a scene, comment on its absurdity, and then steal it outright. Indeed, before The Saint, fiction’s stalwarts were upright, law-abiding, and eminently predictable, more interested in good works than wine, women, and wealth. But since his first appearance in Meet the Tiger in 1928, The Saint has changed all that.

Templar begat James Bond and a whole line of the cinema’s smart-aleck, vigilante protagonists. When Bruce Willis’s cinematic tough guys mock no-nothing, pompous authority figures, he is echoing what The Saint first did in print over 60 years ago. And The Saint is still a phenomenon in his own right. Since 1928, the 64 Saint books have sold over 40 million copies, while the character has appeared in some 14 films (the first in 1938), two TV series (the most famous starring Roger Moore), six TV-movies, a number of radio series, comic strips, bubblegum cards, his own magazine, and now, in what could be the grandest incarnation ever, a $60 million Paramount picture slated for winter, starring Val Kilmer and Oscar nominee Elizabeth Shue. The new movie, says an insider, will present a “Simon Templar for the ‘90s. He is still a playboy but The Saint has been brought right up to date.”

No one would have predicted such a long, prosperous life for the British buccaneer. When he first appeared, the character was simply one of many created in the roaring ‘20s by a 20-year-old Cambridge student named Leslie Charteris (born Leslie Charles Bowyer Yin in Singapore). The young author was fascinated by the flamboyant. He had taken his pen (and later legal) name from Colonel Francis Charter, a notorious gambler and founder of the Hellfire Club. As a youth, he loved pirate stories and began writing thrillers because he felt he could create better fare than what he was reading. Charteris had his own set of adventures to draw from, as well: he had prospected for gold in the jungle, fished for pearls, labored in a tin mine, and worked as a bartender in a country inn – all in the name of adventure.

The Saint, created in a period when fictional “Gentlemen Outlaws” had colorful nicknames like The Toff, The Baron, Nighthawk, and Blackshirt, followed in the Robin Hood tradition: a well-bred, well-dressed hero helping the underdog against a muddled establishment. The Saint, often dubbed “The Robin Hood of Modern Crime,” was an iconoclastic adventurer, whose credo, as expressed in the short story, “The Melancholy Journey of Mr. Teal,” was straightforward: “To go rocketing around the world, doing everything that’s utterly and gloriously mad – swaggering, swashbuckling, singing – showing all those dreary old dogs what can be done with life – not giving a damn for anyone – robbing the rich, helping the poor – plaguing the pompous, killing dragons, pulling policemen’s legs...” The first Saint.

The first Saint.

The Saint stories are fast-paced, intricately plotted, and highly unpredictable, dealing with stolen jewels, unexplained murders, and hair’s breadth escapes. And they are all done in a tongue-in-cheek style that readers of the ‘30s found uniquely brash (a typical Saintly rejoinder: “I hate to disappoint you – as the actress said to the bishop – but I really can’t oblige you now”).

The plots swung from action-packed boy’s adventures to murder mysteries to psychological studies, all written with a distinctive, nonchalant air. In Getaway, for instance, Templar intervenes in a sidewalk beating and is soon swept away in a rollicking saga involving multiple murders, torture, and jewel theft, as our hero dangles from speeding cars, moving trains, and castle windows. “The Story of a Dead Man,” an early short story, finds Templar masquerading as a member of a notorious gang in a multi-layered mystery that keeps the reader guessing right up until the climax, when the Saint is trapped in a gas-filled dungeon. “The Unfortunate Financier,” another short story, shows The Saint playing mind games with a con man who is too clever for his own good.

“When I start to plan a story,” explained Charteris in the 1960s, “the tests which they must meet to satisfy me, are (1) Is the story line conventional? If so, then how can it be twisted to outrage convention? (2) Is this character someone I can see and feel as flesh and blood, or is it a cardboard cut-out that I saw on some screen? If so, what does it need to make it different? I have always wanted to be an originator: let the others imitate me.”

Readers loved Simon Templar’s brand of insouciant adventure, and seven Saint books appeared within two years. “...the public of the grey, depression-cowed early thirties needed The Saint so badly that nothing would have induced them not to believe in him,” observed William Vivian Butler in The Durable Desperadoes. “Or to surrender that all-important illusion that maybe with the help of the right tailor, maybe by continually polishing up their drawling repartee, they might, if only for a moment or two, bring themselves to resemble him.”

“The Saint is a compromise,” Charteris once explained. “He can have all the fun and sympathy of the fugitive from justice, while at the same time his motives are most impeccably commendable. He can be rude to policemen and at the same time do their work for them.”

George Sanders as the Saint.Not surprisingly, Hollywood soon came calling. Louis Hayward was the first cinematic Saint in The Saint in New York (1938), based on a Charteris novel that depicts Templar as a paid avenger, assassinating a series of criminals the law cannot touch.The character’s dark side was considerably softened in subsequent motion pictures (the most well-known of which starred George Sanders) and radio series (one of which featured Vincent Price, who played The Saint as a gourmet whose greatest peeve was being interrupted while dining).

George Sanders as the Saint.Not surprisingly, Hollywood soon came calling. Louis Hayward was the first cinematic Saint in The Saint in New York (1938), based on a Charteris novel that depicts Templar as a paid avenger, assassinating a series of criminals the law cannot touch.The character’s dark side was considerably softened in subsequent motion pictures (the most well-known of which starred George Sanders) and radio series (one of which featured Vincent Price, who played The Saint as a gourmet whose greatest peeve was being interrupted while dining).

By 1962, when The Saint reached television in the person of Roger Moore, he had become more of an amateur detective/playboy than vigilante, traveling the world in search of adventure, tossing off ironical asides as he assisted those in need. In “The Loaded Tourist,” he becomes involved in an Italian jewel swindle/murder plot when he helps a 16-year-old Italian boy search for the murderer of his father. “The Talented Husband” finds him in England trying to outsmart a serial wife-killer. “The Careful Terrorist” brings him to America, as he continues a murdered friend’s campaign against a corrupt union boss. This Templar is recognizably Charteris’, however, with a taste for fine food and good clothes, and a regular nemesis in Chief Inspector Claude Teal of Scotland Yard.

“The stories always have a very good twist,” Moore said in 1966. “The Saint stories have never had the sex of Mickey Spillane or the brutality of James Bond.”

The new Saint movie has been in the planning stages since 1991, and follows a 1978 TV series starring Ian Olgivy, and six 1989 TV-movies with Simon Dutton. It reportedly attempts to make Templar a hero for the ‘90s by returning him partly to his more shadowy 1930s roots. According to a report in Screen International, “Director Phillip Noyce has looked for inspiration to Leslie Charteris' original stories rather than the 1960s TV series...making the character of Simon Templar...much darker than in his small-screen incarnations. ‘I want to portray how a sinner becomes a saint and how someone is redeemed,’ Noyce explains.”

“The character of The Saint is very much the same as he always was,” one of the movie’s producers,William MacDonald, told Burl Barer in The Saint: A Complete History, “although we must say that probably in the interest of establishing exactly why a Saint in the ‘90s becomes a Saint, we are going to create a little more of a back story than was originally related in the books...[but] the classic Saint characterization found in the books should be fully incorporated into the screenplay.”

The Saint features Val Kilmer as Templar, about whom Roger Moore noted recently, “I think he will draw a big audience and make it very successful. As my company is involved in it, I'm very, very happy about it.” Kilmer, whose salary for the movie is in the $6 million range, has played unconventional heroes before: rock singer Jim Morrison in The Doors, an unconventional psychologist in the film noir tale Dead Girl, and the caped crusader in Batman Forever. Leaving Las Vegas Oscar nominee Elizabeth Shue co-stars as Dr. Emma Russell, a young electrochemist who falls in love with The Saint. Lensed in Moscow’s Red Square and the Kremlin, as well as in Toronto and locations throughout England, the movie has undergone a number of rewrites (there have reportedly been five different screenwriters) before satisfying the producers and Charteris, who died in 1993 at age 85. (An early script featured Moore as The Saint’s father, but subsequent plans for a cameo didn't work out; the actor’s son Christian is a video assistant on the shoot, however.)

“A third script has now been started by a new writer who has actually read some Saint books,” wrote Charteris in 1992. “This is, of course, an unprecedented innovation by Hollywood standards.” The finished Saint movie, however, looks to be inspired as much by 007’s cinematic exploits as by Charteris, dealing with cold water fusion and featuring Russian troops and tanks, explosions, and fleeing gypsies on the Moscow subways. Nonetheless, one writer on the film noted to Barer, “I am...connecting as much as possible with the Saint myth and using Charteris’ original dialogue whenever I can.”

Whether the filmmakers succeed in capturing the true Saint or not, one thing is certain: Simon Templar himself will survive, as he always has, with his halo – if not his virtue – intact. “I don’t see why he shouldn’t go on another 30 years,” said Charteris shortly before his death. “He is the last of the fictional swashbucklers in the tradition of Dumas...the last guy who could fight with a laugh and a flourish and a sense of poetry thrown in.”

SAINT SIDEBAR

Roger Moore as The Saint.

Roger Moore as The Saint.

The Saint is coming to the big screen and that has created activity on other fronts. Among the current Saint-related items:

Columbia House Video will release the first volume of The Saint: The Collector’s Edition on October 28, 1996. The collection is available through mail order only. The initial tape, featuring “The Talented Husband,” the premiere black and white TV episode from 1962, and “The Death Game,” a much-later color installment, is priced at $4.95 (plus shipping and handling); subsequent volumes (nine more are scheduled) will cost $19.95 each, plus shipping and handling. Each edition will be sent every four to six weeks.

RKO is remaking the classic Saint films of the 1940s for the USA cable TV network. The first will be The Saint in New York,. The search for a leading man is underway.

Pocket Books has contracted with Edgar Award-winning author Burl Barer to write The Saint, a novel based on the Wesley Strick screenplay of the new Val Kilmer adventure.

Upstairs Downstairs

UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS AT 25

UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS AT 25

By TOM SOTER from DIVERSION, OCTOBER 1999 The setting is a grand dining room table, sometime in 1912. A dapper thirty-something, mustachioed young man has been talking animatedly to a primly dressed young woman who sits at the other end of a long dining room table. The butler stands silently behind him.

“Oh, by the way,” says the man to the butler, “we’ll have a bottle of the Cantenac ’93 with lunch.” He turns back to the woman. “My father has this marvelous claret –”

The butler clears his throat. “Begging your pardon, sir, but I am afraid I cannot serve the Chateau Brane Cantenac ’93, sir.”

“Oh? Why not?”

The butler hesitates. “There are – certain difficulties. If I might see you in private, sir.”

The difficulties, once explained, are relatively simple: the young man, James Bellamy, wants to serve his father’s best claret to his father’s secretary. (“He would not wish it to be served at luncheon,” explains Hudson, the butler, “especially in his absence and in the circumstances.”)

The next day, after he has ultimately been forced to serve the claret, Hudson tenders his resignation. James’s father, Richard, is furious, siding with Hudson: “He’s a man of high principles and, as you well know, he cares deeply for the welfare and honor of our family. And he expects things to be done correctly.”

It is a highly dramatic moment – yet isn’t it just a tempest in a teapot? To us, perhaps, but not to the Bellamy household. And certainly not to the one billion viewers in 40 countries who made Upstairs Downstairs, the series in which the sequence appears, one of the most beloved series of its kind. According to the New York Times, the Emmy Award-winning program was savored by a wildly eclectic audience: Britons and Americans of every stripe, as well as Japanese pearl divers, Nigerian dentists, and the Shah of Iran.

Now, 25 years after it made its American debut, Upstairs Downstairs is back in five boxed sets from A&E Home Video, which, for the first time feature all 68 episodes (including some not shown on the show’s initial American run). And, with it, come all the elegance, drama, and wit of a bygone era. But the show is more than just another classy, slightly staid British costume drama. The series, which spanned an epic period of change in the British empire from 1903 to 1930, looked at the world through the prism of the masters (“upstairs”) and the servants (“downstairs”) in a way never attempted before and never equaled since. “...Upstairs may have been upstairs and downstairs downstairs,” observed Benedict Nightingale in The New York Times, “but together they formed an acting ensemble whose strengths and subtleties television has rarely if ever managed to duplicate...”

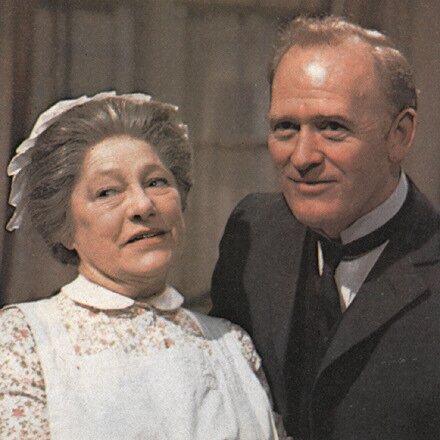

Upstairs: Mr. and Mrs. Bellamy

The basic concept originated with actresses Jean Marsh and Eileen Atkins. Both felt that domestics had never been given a proper spotlight – the popular period drama The Forsyte Saga had just aired, once again offering servants simply as part of the furniture – so the two cooked up a comedy (which they hoped to appear in) involving the masters as seen from the servants’ point of view.

“We were both sick of playing smooth, middle-class ladies,” Marsh recalled, “and, being Cockneys, felt that the working class got as rough a deal on television as they did in real life.”

Their concept (dubbed Below Stairs or The Servants’ Hall) followed the mostly comic adventures of two housemaids who worked in a Victorian country house. They brought their concept to TV producer John Hawkesworth who, with script editor Alfred Shaughnessy, reconceived the series as a drama about servants and masters.

“We wanted to see the servants as people, to look at downstairs as carefully as upstairs for the first time,” Hawkesworth recalled. “This was the pearl in the oyster, the brilliant thing. Up to then servants had really just been mobile props.” As eventually developed, the series would observe the masters and the servants as two separate classes but two similar “families.”

One story would act as a commentary on the other, and the drama often came from how the two groups, living under one roof, dealt with the encroaching outside world. And what a world! There was the death of Edward VII (who had, in one memorable episode, visited the Bellamys for dinner), the glory and then the agony of World War I, the post-war trauma of shell-shocked veterans

The primary setting was a grand, five-story house at 165 Eaton Place (the building used for the exterior shots is still standing at 65 Eaton Place; a “1” was painted in front of the number in an attempt to give its occupants anonymity). Upstairs were the Bellamys, who originally consisted of Richard, an ambitious but principled member of parliament; Lady Marjorie, his oh-so-proper wife; and their troublesome grown-up children, James and Elizabeth. Downstairs were Mrs. Bridges, the excitable cook; Rose and Daisy, the parlor maids; Edward, the footman; Ruby, the comical kitchen maid, and Hudson, the imperious Scottish butler who presided over them all like a major domo and father figure. In developing the characters, the casting was crucial, and the writers frequently altered the roles to fit the actors. When casting director Martin Case saw Gordon Jackson, for example, he felt that he had found his Hudson, even though the man did not match the original conception. “Gordon is Scottish,” Case recalled in Backstairs With Upstairs Downstairs, “so I changed the name to Angus, and then we made him well-educated, even a little erudite – because Scots then generally were – and they were also Calvinists, slightly Puritanical, slightly rigid, so we had him saying grace...”

The producers instituted other key production decisions. Going against the trends of the times, they opted to shoot on videotape instead of more costly film. They would mostly eschew location work and confine the action to a limited number of sets. The money saved in such choices was used to get the best acting and writing talent available – and also meant that the drama would have to be played out in the dialogue and the performances and not rely on the flashy visuals that other period dramas frequently fell back upon.

The series was carefully researched, as well. “There would be long discussions about from which side the salt would be delivered at the dinner table and whether people would drink coffee from a demitasse and stuff like that,” Simon Williams, who played James Bellamy, recalled in a TV documentary about the show. “What gave it extraordinary distinction,” Alistair Cooke observed in A Decade of Masterpieces., “was the sure observation of character, the confidence and finesse with which the social nuances and emotional upheavals between the two groups were explored, and the scrupulous accuracy of the period language, decor, mores, and prejudices.”

To achieve that, Hawkesworth would search the microfilm files of the London Times, studying letters, memoirs, House of Commons debates, store and fashion catalogs, weather reports, song books, and theater programs. The producer then assigned each episode to a writer, who was allowed to bring his or her separate view to bear on any or all of the characters. “Thus,” observed Cooke, “the character of Richard Bellamy or Lady Marjorie or Rose or Hudson was never a single conception; it reflected such unexpected facets of temperament, moments of growth, as one might learn from the pooled memories of a group of friends.”

Downstairs: Mr. Hudson and Mrs. Bridges.

Despite all the accuracy, however, the show could very easily have been a waxworks display, if not for the sharp writing, which could make even the most minor incident – to us, that is – assume major importance. And unlike later would-be-successors like CBS’s Beacon Hill or the current PBS Berkeley Square, Upstairs Downstairs was low-key in its drama but all the more devastating for that. For, as director Bill Bain noted in Backstairs With Upstairs Downstairs, the drama came out of nuances. When James says goodbye to his father as the son goes off to fight in World War I, for instance, the two never embrace – and are more moving because of that. “It was more poignant that they stood there, looked at each other, and didn’t touch,” Bain observed. “There was no release of emotion – which made you release yours. I’ve always thought, watching great actors, that it’s not their ability to cry that moves you; it’s their ability to make you cry.”

Indeed, above all else, the series was popular not because of its attention to detail or its finely crafted scripts. It was because its characters seemed both achingly real and hit a crucial chord during turbulent times. In an era of presidential scandal (Nixon’s not Clinton’s), economic crisis, and ongoing cultural clashes, Americans (and others) saw themselves reflected in the tumultuous period of pre- and post-World War I Britain. Like that country, America (and the world) was adrift, and the Bellamys and their servants held a mirror to popular concerns about order and family loyalty in changing times.

“From time to time I say to myself that Upstairs Downstairs was just a middle-of-the-road television series – what is all the fuss about?” Jean Marsh, who played Rose, once noted. “But I realize it’s just a reaction to having had a little too much praise. It’s very rare for a series to appeal to both the critics and public. We did aim high and, if you aim high and nearly succeed, I think television serials can be the modern-day equivalent of Dickens or Trollope.” But the appeal of Upstairs Downstairs can be seen in even simpler terms: with its warm upstairs and downstairs families surviving both good times and bad, the series is as familiar and comforting as an old friend. It is, as Hudson might say, “very good, indeed, my lord.”