You are hereMagazines 1990-1999 / Television Shows / Upstairs Downstairs

Upstairs Downstairs

UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS AT 25

UPSTAIRS DOWNSTAIRS AT 25

By TOM SOTER from DIVERSION, OCTOBER 1999 The setting is a grand dining room table, sometime in 1912. A dapper thirty-something, mustachioed young man has been talking animatedly to a primly dressed young woman who sits at the other end of a long dining room table. The butler stands silently behind him.

“Oh, by the way,” says the man to the butler, “we’ll have a bottle of the Cantenac ’93 with lunch.” He turns back to the woman. “My father has this marvelous claret –”

The butler clears his throat. “Begging your pardon, sir, but I am afraid I cannot serve the Chateau Brane Cantenac ’93, sir.”

“Oh? Why not?”

The butler hesitates. “There are – certain difficulties. If I might see you in private, sir.”

The difficulties, once explained, are relatively simple: the young man, James Bellamy, wants to serve his father’s best claret to his father’s secretary. (“He would not wish it to be served at luncheon,” explains Hudson, the butler, “especially in his absence and in the circumstances.”)

The next day, after he has ultimately been forced to serve the claret, Hudson tenders his resignation. James’s father, Richard, is furious, siding with Hudson: “He’s a man of high principles and, as you well know, he cares deeply for the welfare and honor of our family. And he expects things to be done correctly.”

It is a highly dramatic moment – yet isn’t it just a tempest in a teapot? To us, perhaps, but not to the Bellamy household. And certainly not to the one billion viewers in 40 countries who made Upstairs Downstairs, the series in which the sequence appears, one of the most beloved series of its kind. According to the New York Times, the Emmy Award-winning program was savored by a wildly eclectic audience: Britons and Americans of every stripe, as well as Japanese pearl divers, Nigerian dentists, and the Shah of Iran.

Now, 25 years after it made its American debut, Upstairs Downstairs is back in five boxed sets from A&E Home Video, which, for the first time feature all 68 episodes (including some not shown on the show’s initial American run). And, with it, come all the elegance, drama, and wit of a bygone era. But the show is more than just another classy, slightly staid British costume drama. The series, which spanned an epic period of change in the British empire from 1903 to 1930, looked at the world through the prism of the masters (“upstairs”) and the servants (“downstairs”) in a way never attempted before and never equaled since. “...Upstairs may have been upstairs and downstairs downstairs,” observed Benedict Nightingale in The New York Times, “but together they formed an acting ensemble whose strengths and subtleties television has rarely if ever managed to duplicate...”

Upstairs: Mr. and Mrs. Bellamy

The basic concept originated with actresses Jean Marsh and Eileen Atkins. Both felt that domestics had never been given a proper spotlight – the popular period drama The Forsyte Saga had just aired, once again offering servants simply as part of the furniture – so the two cooked up a comedy (which they hoped to appear in) involving the masters as seen from the servants’ point of view.

“We were both sick of playing smooth, middle-class ladies,” Marsh recalled, “and, being Cockneys, felt that the working class got as rough a deal on television as they did in real life.”

Their concept (dubbed Below Stairs or The Servants’ Hall) followed the mostly comic adventures of two housemaids who worked in a Victorian country house. They brought their concept to TV producer John Hawkesworth who, with script editor Alfred Shaughnessy, reconceived the series as a drama about servants and masters.

“We wanted to see the servants as people, to look at downstairs as carefully as upstairs for the first time,” Hawkesworth recalled. “This was the pearl in the oyster, the brilliant thing. Up to then servants had really just been mobile props.” As eventually developed, the series would observe the masters and the servants as two separate classes but two similar “families.”

One story would act as a commentary on the other, and the drama often came from how the two groups, living under one roof, dealt with the encroaching outside world. And what a world! There was the death of Edward VII (who had, in one memorable episode, visited the Bellamys for dinner), the glory and then the agony of World War I, the post-war trauma of shell-shocked veterans

The primary setting was a grand, five-story house at 165 Eaton Place (the building used for the exterior shots is still standing at 65 Eaton Place; a “1” was painted in front of the number in an attempt to give its occupants anonymity). Upstairs were the Bellamys, who originally consisted of Richard, an ambitious but principled member of parliament; Lady Marjorie, his oh-so-proper wife; and their troublesome grown-up children, James and Elizabeth. Downstairs were Mrs. Bridges, the excitable cook; Rose and Daisy, the parlor maids; Edward, the footman; Ruby, the comical kitchen maid, and Hudson, the imperious Scottish butler who presided over them all like a major domo and father figure. In developing the characters, the casting was crucial, and the writers frequently altered the roles to fit the actors. When casting director Martin Case saw Gordon Jackson, for example, he felt that he had found his Hudson, even though the man did not match the original conception. “Gordon is Scottish,” Case recalled in Backstairs With Upstairs Downstairs, “so I changed the name to Angus, and then we made him well-educated, even a little erudite – because Scots then generally were – and they were also Calvinists, slightly Puritanical, slightly rigid, so we had him saying grace...”

The producers instituted other key production decisions. Going against the trends of the times, they opted to shoot on videotape instead of more costly film. They would mostly eschew location work and confine the action to a limited number of sets. The money saved in such choices was used to get the best acting and writing talent available – and also meant that the drama would have to be played out in the dialogue and the performances and not rely on the flashy visuals that other period dramas frequently fell back upon.

The series was carefully researched, as well. “There would be long discussions about from which side the salt would be delivered at the dinner table and whether people would drink coffee from a demitasse and stuff like that,” Simon Williams, who played James Bellamy, recalled in a TV documentary about the show. “What gave it extraordinary distinction,” Alistair Cooke observed in A Decade of Masterpieces., “was the sure observation of character, the confidence and finesse with which the social nuances and emotional upheavals between the two groups were explored, and the scrupulous accuracy of the period language, decor, mores, and prejudices.”

To achieve that, Hawkesworth would search the microfilm files of the London Times, studying letters, memoirs, House of Commons debates, store and fashion catalogs, weather reports, song books, and theater programs. The producer then assigned each episode to a writer, who was allowed to bring his or her separate view to bear on any or all of the characters. “Thus,” observed Cooke, “the character of Richard Bellamy or Lady Marjorie or Rose or Hudson was never a single conception; it reflected such unexpected facets of temperament, moments of growth, as one might learn from the pooled memories of a group of friends.”

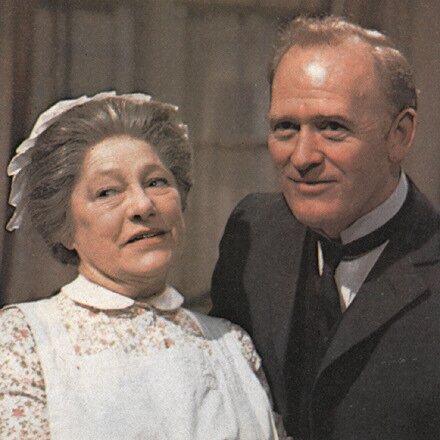

Downstairs: Mr. Hudson and Mrs. Bridges.

Despite all the accuracy, however, the show could very easily have been a waxworks display, if not for the sharp writing, which could make even the most minor incident – to us, that is – assume major importance. And unlike later would-be-successors like CBS’s Beacon Hill or the current PBS Berkeley Square, Upstairs Downstairs was low-key in its drama but all the more devastating for that. For, as director Bill Bain noted in Backstairs With Upstairs Downstairs, the drama came out of nuances. When James says goodbye to his father as the son goes off to fight in World War I, for instance, the two never embrace – and are more moving because of that. “It was more poignant that they stood there, looked at each other, and didn’t touch,” Bain observed. “There was no release of emotion – which made you release yours. I’ve always thought, watching great actors, that it’s not their ability to cry that moves you; it’s their ability to make you cry.”

Indeed, above all else, the series was popular not because of its attention to detail or its finely crafted scripts. It was because its characters seemed both achingly real and hit a crucial chord during turbulent times. In an era of presidential scandal (Nixon’s not Clinton’s), economic crisis, and ongoing cultural clashes, Americans (and others) saw themselves reflected in the tumultuous period of pre- and post-World War I Britain. Like that country, America (and the world) was adrift, and the Bellamys and their servants held a mirror to popular concerns about order and family loyalty in changing times.

“From time to time I say to myself that Upstairs Downstairs was just a middle-of-the-road television series – what is all the fuss about?” Jean Marsh, who played Rose, once noted. “But I realize it’s just a reaction to having had a little too much praise. It’s very rare for a series to appeal to both the critics and public. We did aim high and, if you aim high and nearly succeed, I think television serials can be the modern-day equivalent of Dickens or Trollope.” But the appeal of Upstairs Downstairs can be seen in even simpler terms: with its warm upstairs and downstairs families surviving both good times and bad, the series is as familiar and comforting as an old friend. It is, as Hudson might say, “very good, indeed, my lord.”