You are hereMagazines 1980-1989 / Doctors on Film

Doctors on Film

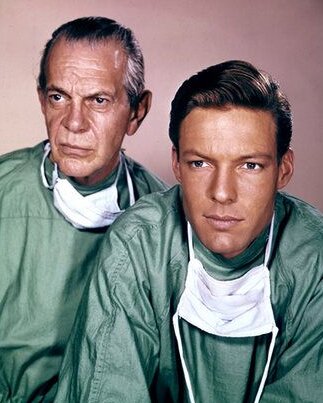

Saintly surgeons: Raymond Massey (left) and Richard Chamberlain in Dr. Kildare.

Saintly surgeons: Raymond Massey (left) and Richard Chamberlain in Dr. Kildare.

THE DOCTOR'S DILEMMA

The Changing Image of the Doctor on Film and in Television

By TOM SOTER

written for MD, October 1989

When Evan Flatow graduated from Columbia Medical School, the keynote speaker was not a cardiologist or a surgeon. He was Alan Alda, the actor. "Ours was the first to have a non-medical figure address our college," recalls Flatow, who now practices in New York. "Everyone was impressed by his character (Dr. Hawkeye Pierce on TV's M*A*S*H). You know, they say a non-doctorr can give a better commencement address than a doctor. And it's true."

Many doctors are also saying that television and film physicians make better doctors than the real thing - at least in the public's eye. "I became a doctor in part because of Ben Casey and Dr. Kildare," notes Dr. Peter Hesslein, associate professor of pediatric cardiology at the University of Minnesota. "When I was coming out of college in the sixties and early seventies, I had a strong urge to be a public servant, and those shows made medicine seem very attractive. Agrees Dr. Thomas Barnard, a cardiologist in New York: "I saw Dr. Kildare as a kid. It was exciting and glamorous." Indeed.

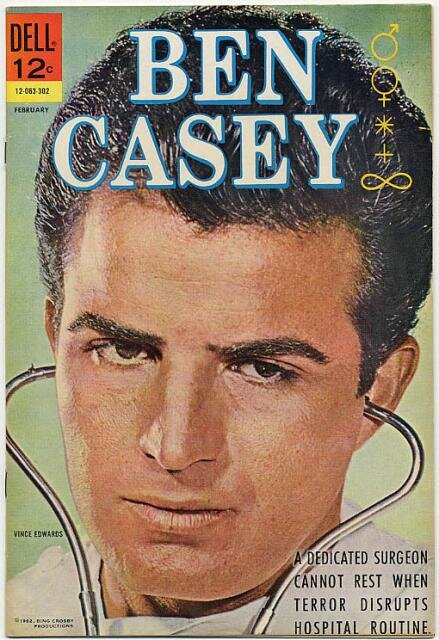

At the height of their popularity in the early 1960s, Kildare and Caseywere watched by 32 million teenagers a week. Comic books, board games, record albums, and even a popular "Ben Casey"' medic's shirt flooded the market, while Kildare star Richard Chamberlain became a recording star with a vocal version of his show's theme. "Ben Casey was sort of like a surgical Perry Mason," observes Carole Mann, a fan in Amarillo, Texas, in Cult TV. "He was the kind of take-charge guy that I thought I'd want to marry - totally in control."

To the public at large, that was the standard image of a doctor: "We were made into kind of demi-god," says Dr. Christine Edwards-Freeman, a New York-based obstetrician and gynecologist, an all-knowing figure, dispensing words of wisdom with a helpful injection. Those beliefs were borne out by a poll taken in the 1960s that found the public rated physicians second only to the Supreme Court justices for compassion, integrity, and sagacity. No longer. In an age of cynicism, doctors – like most extablishment figures – are viewed with increasing mistrust.

"We now get a lot of negative press," claims Dr. Steven Lamm, a clinical assistant professor of medicine at the New York University School of Medicine. Agrees Hasslein: "People used to expect miracles from doctors. We were viewed as geniuses. Not anymore."

An October 1989 New York Times op-ed article, for example, discussed hospital care, concluding with the observation: "We can no longer assume that the interest of the health provider is in the best interest of the consumer. Health care is big business." How did it come to that? And what role did films and television play in the real-life doctor's fall from grace? To understand, we must examine the fictional physician's long-standing image.

"He was usually strong-willed and humanitarian," notes Dr. Mark Goetting, of the pediatric-intensive care unit at the Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. "He was good, but shallow in the sense that there was almost never a struggle about the right or wrong of what he was doing. There would never be a questioning of medicine or of the procedure."

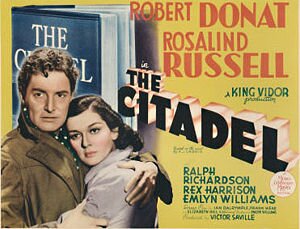

In such films as Calling Dr. Kildare, Magnificent Obsession,and The Quiet Duel, the physician was a noble superman who could cure illnesses in a single bound. So great was his power that on Emergency, a 1970s TV series about paramedics, he could operate on a lamb suffering from smoke inhalation and cure him. To Ben Casey (Vince Edwards), the "operating room [was] like a church," and the surgeon was the divine messenger. So much so, in fact, that in The Citadel(1938), the idealist new doctor (Robert Donat) must battle mistrust and hatred to cure tuberculosis. "I'm not going to be influenced by ignorance and superstition!" he cries out messianically. "I'm working for these people and will not let their stupid prejudices stop this work!" As the elderly Dr. Zorba (Sam Jaffe) explains on Ben Casey: "We ae not just men. We are doctors...Therefore we can and must work under great stress."

Ben Casey comic book.

Even when doctors are shown to be less-than-good – as they are in The Citadel in which most physicians are more interested in relieving bank accounts than pain – the bad side is depicted simply to highlight the good. "Your work isn't [to earn] money," remarks the hero's wife (Rosalind Russell). "It's bettering humanity."

That impression persisted through countless films and TV series, aided and abetted by the American Medical Association (AMA). To needy producers and writers, the AMA offers lists of doctors who can act as consultants. To news reporters, it provides footage and reports on the latest medical breakthroughs, along with packaged interviews of physicians. Consequently, in such TV shows as The Doctor, Doc Corkle, Doc Elliiot,, D. Hudson's Secret Journal, Medic, Rafferty, The Nurses, Marcus Welby M.D., The Interns,and Casey and Kildare, the physicians as missionary soon became a cliched portrait as the medico offered drugs and psychological insights.

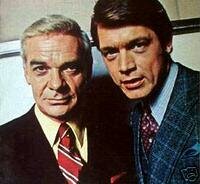

"You chose the wrong girl," dynamic Dr. Joe Gannon (Chad Everett) advises a patient on Medical Center. "She was unhappy, lonelly. She's willing to trust her life to you. If that doesn't make you somebody, then all your dreams and fantasies weren't true!"

The effect all these shows had on the public was clear-cut. "Adult patients in general expect a doctor to wear a white coat, be slightly gray at the temples, stroke his chin and say, 'hmmm,' a lot," notes Hesslein. Agrees Lamm: "The physical appearance of the doctor on TV is of a suave, sophisticated, and elegant person. And on TV, hospitals are always neat and orderly – not frenetic as many hospitals are. We can't meet those expectations." The film and TV doctors spend whatever time it takes and whatever care is needed to find a solution.

On Ben Casey, the smolderingly handsome Casey becomes obsessed with the problems of an elderly architect who may or may not have suffered a stroke. On Trapper John, M.D., recalls Goetting, "Trapper would buck the system and lose his temper – not because he was a person who was having a bad day but because he was indignant that he didn't have enough money to treat a patient. When a doctor failed – as one did on Medical Center, collapsing from overwork – it was only because he was so dedicated and selfless that he was pushing himself to an extreme. Explains Goetting: "Here is a person so concerned, so essential, that he is running himself down."

The Citadel: MDs as fallen angels.

The Citadel: MDs as fallen angels.

In addition, doctors always knew best. "Their course is always well-planned and interference would be for some social reason, like a religious objection to the transfusion of blood," notes Goetting. "There was never a questioning of the medicine or the motivation of the physician. The doctor was always right."

In Life for Ruth, for example, a dedicated doctor (Patrick McGoohan) battles the religious beliefs of a young girl's parents in an attempt to get her a life-saving blood transfusion. Because of such portraits, notes Edwards-Freeman, "everyone comes to the doctor with a pain and you're supposed to feel them and say, 'Ah ha! This is why you're suffering,' and then cure them. The media has built us into gods." Adds Barnard: "Most of these shows succeed in terms of technical accuracy, except that the doctors always had a textbook case, with the latest state-of-the-art therapies available. In real life, however, you don't have a textbook disease. Usually you have an array of complicated problems: diabetes, heart disease, hyper-tension, problems at home with your wife. Real [health-care] problems don't fit into a slot as neatly as we like."

The media image has created some dangerous stereotypes, as well. "In cardiac arrest, less than 10 percent of the patients will wake up. You may be able to get the heart restarted, but there is usually massive brain damage. Yet if you watch Emergency, you'd think CPR is wonderful. It creates the impression among the public that once the paramedics arrive, everything will be okay. That's not the case."

Similarly, many medical shows put forward almost magical surgical solutions – heart and liver transplants, for instance – that mislead the public. "Heart transplants are not performed that often," explains Barnard. "You have to have the right patient and the right situation. You wouldn't give a heart transplant to someone who had a multi-system problem, where the heart is sick and so is the liver and something else might fail."

Medical Center's James Daly (left) and Chad Everett.

Television images create other misconceptions, too. "People expect to see a male doctor," says Dr. Marcia A. Harris, a New York obstetrician and gynecologist. "A lot of times, patients can't accept the fact that I'm a doctor. They think I'm a nurse. Especially the older womem. They'll say, 'Send me the real doctor.' I say, 'Honey, I'm as real a doctor as you're going to see.'"

Other times, the sick cannot understand why there is no answer for their ailment. In Ben Casey, a stroke victim is cured through surgery (after Casey discovers it wasn't a stroke after all), while on Medical Center, a young woman with a benign tumor on her spine is saved via an operation (and also finds true love with another patient). Marcus Welby takes such cures to ridiculous extremes, as the folksy Welby (Robert Young) diagnoses and treats the most exotic diseases imaginable.

"For a family pediatrician," observes Barnard, "he saw an amazing variety of diseases – the kind that a major medical referral service like Massachusetts General Hospital might see. He would always find the cure." (While in medical school, Barnard and his fellow students often tried to diagnose the weekly rare disease before Welby did. "It was a great game," he says.)‘

Yet, claims Edwards-Freeman, "the TV producers have, if you'll pardon the expression, 'doctored' things up a bit. Illnesses don't always work out well." Agrees Lamm: "Television has greatly exagerrated our ability to cure everybody. We are given omnipotence." In real life, adds Barnard, "sometimes people get better and go away and you never know what it was that was bothering them. That's disconcerting to a patient. He never knows what he had; but you can't have doctors on shows come in and say, 'We don't know what you have. Rest at home and come and see me in two days.' That's not what people expect." Barnard cites the first experience he had with AIDS in 1978. "We took tests, offered treatment, but just couldn't figure it out. And that happens real often. But the shows give you the idea if you get something, go to the doctor, he'll put a label on it, give you some medicine, and you'll get well."

Lionel Barrymore (left) and Lew Ayres in a Dr. Kildare movie.

That raises another issue: depicting the mundane. Not every case is as dramatic as the ones on television, and some require extensive and boring treatment. "The media want a cure for cancer every day," says Dr. Alan Matarasso, a New York plastic surgeon. "When they do a TV program or a movie, they're not interested in the nuts and bolts work, they want action. But 50 percent of an intern's time is not spent cutting up victims: it's doing scut work: drawing blood, taking someone to a chest X-ray."

Adds Barnard: "There are a lot of things that are chronic, that patients have to live with. And chronic problems are not very dramatic. You don't see a guy coming in for treatment – one day he's better, the next day he's worse. That's not very exciting."

By not showing such aspects of the physician's work – as well as ignoring his paper work and home life – these programs made it difficult for patients to understand why doctors couldn't spend as much time with them as the TV physicians do. "On television," remarks Lamm, "a doctor sees one patient throughout the show. I'm seeing 30 patients a day. There was a time when physicians would go to the office early, see maybe 40 patients, then go on house calls, then get home at 10, 11 at night. Today, physicians are demanding a little more of a private life. A lot of doctors are not willing to work from 8 A.M. to 11 P.M. It's not good for a normal human being and is counterproductive. If I go home at 7, I'll be a more sane individual."

Yet the image persists. On Quincy, a crime show about a crusading forensic pathologist who is a former private practice physician – Dr. Quincy (Jack Klugman) will order multiple tests on individual cases, undertaking a lot of the investigative footwork himself. "It's very unrealistic," complains Goetting. "In Detroit, the average number of bodies that arrive for an autopsy in a morgue is 11 per day. Plus there is a very tight budget. If the state ordered the number of tests Quincy did, or spent that much time on individual cases, the other cases would suffer. On Quincy, it looks like time and money are no object. The mission is paramount. That's just not accurate."

Toshiro Mifune in The Quiet Duel.

Money restrictions are the reality. With rising costs caused by rent, staff, malpractice insurance payments, and medical school bills, many doctors must see as many patients as possible. "Bill Cosby plays a doctor on The Cosby Show but he always seems‘ to be at home," says Edwards-Freeman. "I guess personal envy is involved, but I wonder how he does it." Agrees Dr. Michael Mitchell, a New York pediatrician: "You are on call 24 hours a day. Marcus Welby hurt our image. You would see Welby, with no bags under his eyes, always refreshed, smiling, perky. He was never rushed because he had a roomful of people in the waiting room."

"The costs of doing health care, malpractice insurance, and hiring a well-trained staff are causing physicians to become businessmen," notes Dr. Richard Stein, acting chief of cardiology at the State University of New York Health Science Center. "We have to charge more, see more people, and our income is still diminishing. If I was primarily interested in money, it would make more sense today for me to get a two-year MBA or a three-year law degree. That's more cost-effective than four years in medical school and six years in post-graduate."

Such costs are cutting into the humanitarian aspect most often depicted on television. Matarasso points to a colleague who did Medicare work and was reimbursed only 37 cents. So he says, 'To hell with it. I won't see indigent patients, only well-heeled ones.' The government says take care of the indigent, but what profession can afford to do pro bono work? If I go to a clinic and stitch on some guy's hand and it doesn't work properly because the guy didn't follow instructions, some lawyer can sue you for malpractice. I did it for free, so who needs it? They say there are two ways to get rich: win at Lotto or sue a doctor.'

These pressures were rarely explained in medical shows – until St. Elsewhere premiered on NBC in 1982. Here was a new kind of doctor show, one that explored the personal stresses of being a physician. Depicting a seedy hospital called St. Elgius in Boston, a typical episode might depict a doctor being mugged in an emergency room, a mentally ill patient wandering the halls, and/or two doctors making love on a slab in the morgue. "That series came closest to my experience as an intern," notes Dr. Elissa Ely, a Cambridge psychiatrist who did a medical internship. "The doctors suffered. They laughed. They cried. They lost patients. It was bloody." On it, doctors made mistakes. In one installment, a patient died because of the faulty administration of a drug. "The doctor involved falsified the records," recalls Goetting. "That kind of thing happens. The program also showed conflicts that go on at hospitals: nurses bickering with doctors, rivalries and mistakes among interns. The accent was on the interpersonal." Dr. Craig (William Daniels) in St. Elsewhere "was dogmatic, condescending, arrogant," adds Goetting. "Technically, he's a good surgeon, but he offends people because he's so arrogant. On occasion, he would make a mistake. But you could understand why."

Nonetheless, for all St. Elsewhere's realism, many physicians feel it, too, is a fantasy. "There's just more drama than you'd find in an average hospital," remarks Barnard. "People being killed in car wrecks, murderers and rapists running loose – it does happen, but not every week. That can skew the perspective." Some claim, though, that such shows have really helped create a balance by offsetting the omnipotent image of the past. "I don't know if the stereotype of the decadent doctor first appeared on TV or if TV just reflected a public perception," says Goettling, "but television doesn't depuct physicians as missionaries anymore. It depicts them as people of undistinquishable motivation."

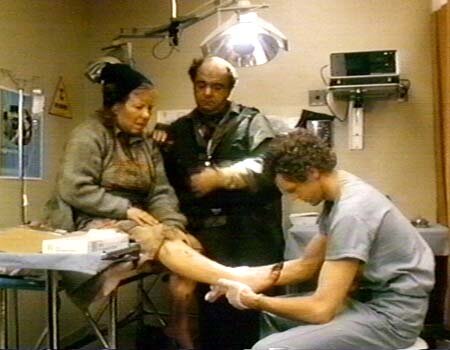

David Morse in action on St. Elsewhere.

David Morse in action on St. Elsewhere.

"What's good about these medical shows is that they show a side that nobody in medical school bothers to explain," remarks Dr. Charles Goodrich of New York. "There is a human side to being a doctor. Students are taught medicine but not how to help the human being to get better and healthy, which is a complex affair, involving science and sociology."

Notes Lamm: "A lot of physicians treat the disease, but it takes a lot longer to treat the patient. In the old days, all we could do was hold their hands and watch them die. But now medicine is so much better, we don't have to spend as much time with them."

Lamm recalls a visit from an 82-year-old woman with a cough. Within a minute and a half, he had diagnosed the problem, "but I couldn't just say that. It wouldn't have been satisfactory to her. I had to hold her hand and explain the symptoms, that she'd have this cough and that it was normal and tell her that she'd live. That's important – and it takes time." "Until we face the fact that cures are not just microbiological, we're going to miss the boat," adds Goodrich. "You've got to look at the psychosocial cause of a disease, as well. The roots of cancer lie in a subtle interweaving of internal and external stresses. AIDS is a good example. There is a human health solution: reduce AIDS risk behavior rather than just treat the disease." In the end, most physicians agree that all cinematic and video doctors are based on an important societal need.

"From a patient's point of view, a lot of what we do is magic," explains Hesslein. "I think for our work to have an effect, that has to be. I firmly believe that if a patient believes in what you're doing, you're on the right track. He will feel better no matter what you do. That's why shows like Kildare, andCasey had a strong public following. Patients like to look on us as almost faith-healers, and we may be happy to foster that belief. It might not be an honest view. But it's what people want doctors to be."