You are hereNewspapers 1990-1999 / Upstairs Downstairs

Upstairs Downstairs

The Continuing

Appeal of

UPSTAIRS

DOWNSTAIRS

By TOM SOTER

for THE NEW YORK TIMES, 1999

It has been 29 years since the early 20th century costume drama, “Upstairs Downstairs,” premiered on British television. And, by all rights, it should be as forgotten today as the creakiest of kinescopes. Shot on videotape and generally confined to indoor sets, it has long since been surpassed in production values by such sweeping mini-series as “Tom Jones” and “Vanity Fair.” And, unlike many of today’s fast-paced melodramas, the series was defiantly leisurely in its approach – favoring long takes and silent reaction shots – and positively mundane in its concerns: should a butler serve the master’s best claret to a secretary or not?

Yet “Upstairs Downstairs” made the mundane memorable, the leisurely luxurious. And, these days, it is positively thriving. In 1999, A&E Home Video began releasing the entire 68-episode series on video, including a number of episodes not generally telecast (the first three seasons are in stores now; the last two will be coming out later in the year). There is also an “Upstairs Downstairs” web site featuring commentary, notes, and trivia; a television documentary came out in 1996, and at least two books about the series are in the works. The term “Upstairs Downstairs” has even entered the critical lexicon. When a recent British import, “Berkeley Square,” appeared here, critics – without any further explanation – labeled it “Upstairs Downstairs”-like (it wasn’t).

That should not be news to those who know the show. After all, “Upstairs Downstairs” has been wildly popular with audiences of all stripes since its inception: Britons and Americans took to the drama immediately, as did Japanese pearl divers, Nigerian dentists, and the Shah of Iran. As unlikely a fan as TV cop Jack (“Just the facts, ma’m) Webb of “Dragnet” fame even proposed a sequel series (which, unfortunately – or fortunately, perhaps) never came to pass. Later TV costume dramas like “The Pallisers” and “The Duchess of Duke Street” may have aped the forms of “Upstairs Downstairs” but none have ever matched its appeal or influence.

The series spanned an epic period of change in the British empire, from 1903 to 1930, looking at the world through the dual prism of the masters (“upstairs”) and the servants (“downstairs”). In its sweep and its emphasis on family, the show echoed Noel Coward’s play, “Cavalcade.” But it was different in one respect: no one had ever depicted servants so sympathetically or in such loving detail.

In previous dramas, Alfred Shaughnessy, the script editor for the series, recalled, “servants had not really had proper lives of their own. A footman would come in and open the double doors and announce, ‘Mrs. Ervin,’ or something. What we did was to follow that footman downstairs into the servant’s hall and see him take his jacket off and flop into a chair and start chatting with the other servants about what was going on.”

Although there is some dispute about how the series was developed, everyone agrees that the basic concept originated with the actresses Jean Marsh and Eileen Atkins. Both felt that domestics had never been given a proper spotlight – the popular period drama “The Forsyte Saga” had just aired, once again offering servants as part of the furniture – so the two cooked up an outline for a program (in which they hoped to appear) involving the masters as seen from the servants’ point of view.

Upstairs: Mr. Bellamy and Lady Marjorie.

“We wanted to do something that we might know about, that echoed our backgrounds, because my mother had been in service and had been a maid,” said Ms. Marsh, who ultimately played Rose, a maid. “We wanted an audience to see their reality.”

According to John Hawkesworth, who produced the show, the two women’s concept (dubbed “Below Stairs” or “The Servants’ Hall”) followed the mostly comic adventures of two housemaids who worked in a Victorian country house (Ms. Marsh recently disputed this recollection, however, insisting that theirs was a dramatic treatment). They brought their idea to Mr. Hawkesworth and John Whitney, partners and TV producers at London Weekend Television who, with Mr. Shaughnessy, shaped the series into an Edwardian-era drama.

“The actual pearl in the oyster was that Jean and Eileen said, ‘Let’s do something that is half upstairs and half downstairs,’ ” Mr. Hawkesworth recalled. “No one had really done anything concentrating on how the servants felt and behaved. That was the brilliant thing.”

As eventually developed, the series would observe the masters and the servants as two separate classes but two similar “families.” One plot thread would act as a commentary on the other, and the drama was frequently drawn from how the two groups, living under one roof, dealt with the encroaching outside world.

The primary setting was a grand, five-story house at 165 Eaton Place (the building used for the exterior shots is still standing at 65 Eaton Place; a “1” was painted in front of the number in an attempt to give its occupants anonymity). Upstairs were the Bellamys, who originally consisted of Richard, an ambitious but principled member of parliament; Lady Marjorie, his proper, wealthy wife; and their troublesome grown-up children, James and Elizabeth. Downstairs were Mrs. Bridges, the excitable cook; Rose and Daisy, the maids; Edward, the footman; Ruby, the comical kitchen maid and Hudson, the imperious Scottish butler who presided over them all like a major domo and father figure.

This tale of family and work was told in separate narrative arcs that would eventually overlap – a technique that some feel influenced such later dramas as “Hill Street Blues” and “Ally McBeal.”

“The show borrows from daytime serials and even anticipates evening drama in the ‘80s and ‘90s where characters grow over a series of episodes,” said Ron Simon, the television curator at the Museum of Television and Radio. “Many of its techniques were brought into the cop show, ‘Hill Street Blues,’ which mixed family and work life of the characters. The same applies to ‘Ally McBeal.’ What [creator] David Kelley does is go back and forth between professional and personal life. The underlying structure may be disguised, but it’s really from ‘Upstairs Downstairs.’”

The series was helped by some key production decisions. Because of budget constraints, Mr. Hawkesworth opted to shoot on videotape instead of film. Making a virtue out of that necessity, the producer told the writers to eschew pricey location work and confine the action to a limited number of sets. The money saved in such choices was used to obtain top-notch acting and writing talent – the novelist Fay Weldon wrote the first episode – while many of the actors were drawn from the British stage.

The production limitations also meant that the drama would have to be played out in the dialogue, avoiding the flashy visuals of other period series. “I thought it was very important that television drama should be more electronic theater than film,” Mr. Shaughnessy explained, “because on a television screen in those days, a cavalry charge looked like a lot of flies falling off the screen. The best TV drama is about people. It’s a play of character, in a more theatrical sense, more like the stage. So that was the way we did it.”

Part of the continuing appeal of “Upstairs Downstairs” can also be seen in the way it enlivens history by depicting – subtly and without bombast – how contemporary events affected the lives of the masters and servants. The sinking of the Titanic, the death of Edward VII, the “War to End All Wars” (World War I), the war’s aftermath, and the Wall Street crash are all movingly and effectively depicted through the actions of the family and servants.

Another part of the drama’s appeal lay in its careful attention to period detail. Simon Williams, who played James Bellamy, recalled that “half the rehearsal was about the emotional thrust of the character, but when [Mr. Hawkesworth and Mr. Shaughnessy] came they would be very concerned about, ‘Oh no, I don’t think they would have the salt shaker on the left,’ and, ‘I don’t think the butter would be served by the maid, it would be served by the butler.’ So there would be a lot of reminiscing about protocol, about social niceties and things.”

Such concerns are not just production oddities; they are a crucial element of “Upstairs Downstairs,” helping the viewer visit a vanished world of nuance and order. And to recreate that world, Mr. Hawkesworth searched the microfilm files of the London Times, where he studied letters, memoirs, House of Commons debates, store and fashion catalogs, weather reports, song books, and theater programs. “I was actually a sort of historian at Oxford,” the producer explained. “It was my special subject, history. So I’ve always very much enjoyed research.”

At the beginning of each season, Mr. Hawkesworth and Mr. Shaughnessy, who wrote many of the episodes themselves, met for a full day with their fellow writers, hashing out scenarios. They would then assign each episode to a scenarist, who was allowed to bring his or her separate view to bear on the characters.

“We had complete freedom and nobody meddled,” Rosemary Anne Sisson, one of the writers in the series, said. “There was no interference from above, like ‘Can we have more downstairs scenes?’ None of that happened. The stories evolved very, very naturally.”

Still, other series have matched such period detail; many shows before and since have depicted the mores and manners of the British upper classes. Why does “Upstairs Downstairs” continue to fascinate?

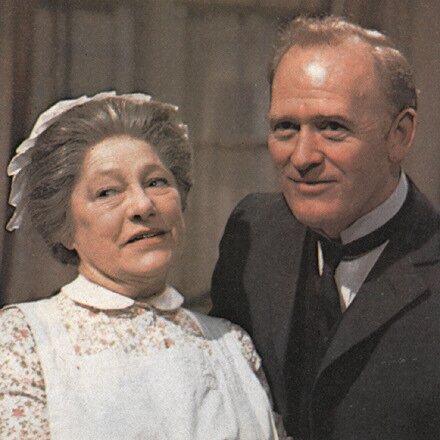

Downstairs: Hudson and Mrs. Bridges

Downstairs: Hudson and Mrs. Bridges

Some argue that it came at a key, unsettling time. In 1974, when it made its American debut, President Richard Nixon was in the midst of the Watergate scandal that would lead to his resignation. The country was suffering through economic uncertainty and ongoing cultural clashes. Viewers then – and now, facing similar uncertainties – could see themselves reflected in the tumultuous period of the pre- and post-World War I Britain of “Upstairs Downstairs.”

“When we’re in a period of turmoil, there’s an unconscious reaction by people to want to go back to a more structured time,” Robert R. Butterworth, a Los-Angeles based clinical psychologist, explained. “When in doubt, people tend to go towards stability. That show was set in a more comfortable, ordered time.”

“We showed a very secure society,” Ms. Sisson agreed. “In spite of all the strains and pressures, it’s a very comfortable society where everyone knows their place. Things like that have broken down so much.”

In the end, there have been many would-be successors, imitators, and even ill-advised sequels (“Thomas and Sarah,” a failure, followed the adventures of a chauffeur and maid after they left the Bellamy household), but none have matched the continuing popularity of the original show. The series has been emulated but seems impossible to duplicate.

Part of that is because of the fortuitous confluence of casting, writing, and producing talent. But the main reason is the program’s emphasis on the family and its concerns. A recent pretender, “Berkeley Square,” may look like the Bellamys redux but plays out as an over-the-top soap opera because its conniving (and unappealing) servants try to outsmart – not assist – their lecherous (and equally unappealing) masters. “Upstairs Downstairs” always found the heart in its characters.

Mr. Hawkesworth, who admitted he was somewhat baffled by the series’ long-time success, offered one theory: “I think the secret of the whole thing is that they are good stories about people that grip you. The most important thing in all entertainment is the script. We concentrated very hard on that, so they’ve endured quite well.”

Mr. Shaughnessy agreed, but felt there was another reason for the appeal of the program. “By having all the servants downstairs and the family upstairs, everybody in every class could identify with somebody,” he said. “In other words, the man in the street could identify with the butler or the footman and so on, while the nobs could identify with and understand the nobs. We had something for everyone.”