You are hereMagazines 1980-1989 / Street Performers

Street Performers

FOOTLOOSE

MUSICIANS

By Tom Soter

from F: FUJI FILM MAGAZINE,

published in Japan, 1987

Translated from the Japanese

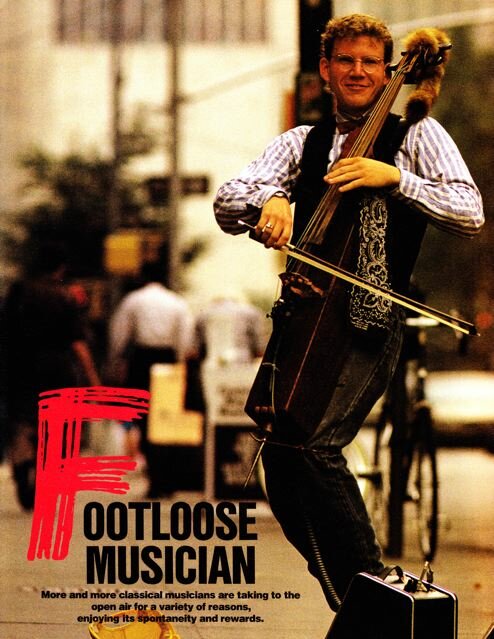

Sean Grissom

Sean Grissom

New York's Columbus Avenue is a residential street, lined with 10- and 1l-story buildings. At night, however, it becomes an unofficial entertainment center, in which a man juggles fire for a crowd of onlookers, another races turtles, and classical musicians oboists"

violinists, miramba players, and cellists -- offer Bach, Brahms, and Haydn in a ''lay they've never done before. On the street.

Street performing has been a way of life in New York for almost as long as there have been streets. And more and more classical musicians are taJdng to the open air for various reasons,and with varying results. There's Sean Grissom, the 26-year-old commercial artist from Texas, whose "Cajun Cello" – a modified antique cello which allmiS him to perform bluegrass music as roll as the classics – has won him numerous street contests (as well as three trips to Japan).

Or Robert Teitelbaum, the 33-year-old former contracts collection agent who spent seven years at a job he hated before giving it all up for music on'the streets. Or Ronald Viogiani, 22, the low-level clerk at the Fashion Institute of Technology and grandson of an amateur drummer who dreams of Carnegie Hall – but for now plays on the streets and in the parks of New York.

They're all tied together by their love of music and their work on'the streets, yet all have different approaches to this unusual profession. "A lot of performers get into this late in life," says Teitelbaum. "It's not the sort of career choice you make early on. You fall into it."

Take Teitelbaum himself. He had studied music for four years and then entered a graduate program in which he practiced on his marimba four or five hours daily. Then, one day, he woke up and said to himself, "I'll never practice again." And he stopped playing. For seven years.

"I said, 'Why am I doing this?' I forgot the reasons why I went into it. Then I was training to be a classical performer, I had lost that special something that had drawn me into music. I wasn't in love with it anymore."

Street performing rekindled the romance. The ex-musician was working for his family firm at a contracts collection agency and also taking a course in marketing when he saw a miramba player on the street. He was fascinated by her grace, her music, and the warm response of the crowd. He became excited about the miramba and seven months later he was out on the street himself. "Part of performing is an ego trip," he notes. "I wouldn't be there if people dictll't smile and respond. Part of the gratification is knowing you did it \rell."

"Street performing changed my perspective on what muSic is and what performing' should be," observes Valerie Naranjo, the marimba player who so inspired Teitelbaum. The 27-year-old musician came to New York from Colorado in 1981 and needed a quick thousand dollars for graduate school studies. She took her seven-foot long, l40-pound marimba -- a percussion instrument that creates many haunting melodies when struck .. lith mallets in front of the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue and played. And played. And played.

The crowds were large and generous, and she made as much as $25 to $50 an hour playing Bach, the Beatles, and contemporary West African music. "It's a balance between what I want to play and what people enjoy listening to," she says. "Hopefully, there's overlap."

Although money was her original objective, that soon changed. "I stopped seeing myself as the center of the performance. The center was the energy created by bringing people together with the music and the instruments. Not enough of that goes on. 'We live in a society where the arts are a commodity and an industry rather than something that people share. That's unlike India or Africa where people as a whole participate in art as part of their lives. The closest thing to that here seems to be street performing. It makes something as mundane as walking home from 'work an artistic experience."

Indeed, the success of street performing has led to sUbway performing, a t'io-year-old, city-sponsored arrangement called MUNY (Music Under New York). Funded with a $70,000 grant, the program allows 50 musicians to play classical, jazz, and blues at selected sub'vay stations throughout New York. "The crowd down there is different," says Naranjo. "They're working people. They take it much differently than people strOlling around Central Park do. In the parle, I feel it's more of an entertainment. In the subway, it's much more a salve because everything is so unpleasant."

"I don't like that kind of crOWd," notes Teitelbaum. "It's rushing by you. I like to catch people in a leisure situation. A rush hour crowd tosses you a quarter and listens for two seconds. That's tainted money. They're giving it for pity, not because they enjoy the music. I \vant people to listen."

That was Gary Kvo' s approach, as well. A 22-year-old Julliard Music School student, he needed money when he first came to the city three years ago from a small town in Connecticut. He brought his sky blue-colored violin out on the street, hOOked it up to a battery-operated amplifier and began playing classical music. Small groups of people would gather aria applaud. They were all struck by the intense young man who refused to talk to anyone and seemed to be alone in a world of Dvorak, Stravinsky and Handel -- a world far removed from the rumbling streets.

Detail from a page of the original article, in Japanese.

Detail from a page of the original article, in Japanese.

"I wasn't doing a comedy show," says Kvo, who numbered among his audience Yoko Ono (she once dropped a 20-dollar bill in his case). Yet he admits that are great differences between the street and the concert hall. "When you're performing for concert audiences, they're there because they want to hear you. When you're on the street, you have to grab people's attention. Playing on the street doesn't mean lowering the quality. It's just a different demand. If you can find something people like, you're in luck. It kind of challenges you to see how fast you can do get them. You sell yourself."

"On stage," adds Robert Teitelbaum, "you're 30 feet away. On the street, you can reach out and touch your audience. Doing the street has made me less of a musician in the classical sense and more of an entertainer. It's different from the concert hall because you have to coerce them. If you played classical music beautifully you wouldn't attract them. You need more razzle dazzle." Kvo 'concurs. "Lively music worles better than slOl,er pieces. Often I would play one piece that looks a lot more difficult than it is."

Teitelbaum has adopted different tactics for different crowds. lilt works better if I have a 20-minute set and then pass my hat. That breaks up the shows and gives a definite point for people to contribute., I've also added audience participation, where audience members come up and join me for simple duets on the marimba. I got the idea from watching people 'iatch me. They always want to come up and hit it. So I'm fulfilling a need for them to become involved." Tei telbaum' s course in marketing has also been a big help. "You have to understand your ma;:-ket. I look at what happens when I play certain tunes, or make changes in my presentation. A lot of performers don't do that. They just play. They don't seek out crowds and locations that are suitable to their music. It's like the guy who sits in a dark corner and strums his guitar and wonders why no one pays attention. What to do and how to do it ma]{es a big difference in the attention you get."

Sean Grissom would agree. An unorthodox cellist, he is probably the most visibly successful classical performer on the New York streets. Besides making a living from his curbside earnings, he has traveled to Japan three times, the first as a representative of the United ,States at the World Street Entertainers Festival, where he hobknobbed with street performers from England, Holland, Brazil, and ~rance. This year, he will spend six weeks in ToJ'Y0 and Osaka for the Fuji Television Electronics Exposition.

"It's the damndest thing," he observes. "From playing on the street to going to Japan. I love to see my snob colleagues in the classical business who look do,m on street performing. When they hear what I'm doing it really shakes them up."

He has also started a small record company called Endpin to publish, record, and sell his street music. In 1986, he sold over 3,000 cassettes of Cajun Cello Live! and he has just order 2,000 more. He met his business partner/manager through a street performance connection and \Vas also elected to the New York Cello Society because of the notoreity he had gained on the street. Grissom, who has degrees in commercial art and music performs an interpretation of the Japanese song "Cherry Blossom," as well as cello arrangements of Bach, Dvorak, Saint-Saens, the Beatles, and a Spanish flamenco number. "I get people to listen \~ith the lively music and then sneak into the·classical stuff."

He has ingeniously adapted his cello to the street, mounting a tiny taperecorder in the rocJ{ of it which provides piano accompaniment. He has also added a strap to the instrument so he can dance to his tunes and more freely interact with the crowd. He receives nickels, dimes, subway tokens, Atlantic City casino chips, and foreign coins (he has a collection of ones from Brazil, France, and Holland). "The street's been really good," he notes. "I got skilled on the streets and I can do my o\m thing. I don't have to deal with the hassles of a club unless I want to. I can make more on the street and play for five hours."

Page of original article.

But there are a number of drawbacks that all classicists report -- not the least of "hich are the rough conditions. The police can be the biggest problem. Gary Kvo remembers collecting a crovd of 15 or 20 people with his music and noticing that a police car had pulled up to the curb. An officer got out and stood watching the show. Kvo felt his time "laS up. Although there is no la\V against performing on the street, the POlice can arrest performers for disturbing the peace. "I thought he was going to wait for me to finish IiIy act and then take me away," recalls Kvo. At the end of the performance, however, the officer \ialked up to the artist, handed him a five dollar bill and said, "You're good."

There are also weather problems. Grissom played for only 10 minutes in 120-degree heat and nearly collapsed, while Teitelbaum was caught in many thunderstorms that could have damaged his instrtnnent if he hadn't brought a tarpaulin. And Kvo often had to stop if the wind became too strong and started blowing away his money.

But the biggest headache is coping with the noise. "It's very hard to play outsid~/" says ~ona~d Viogiani, the 22-year-old clerk who is a clarinetist with the New Trio d'Anches, a woodwind trio that won a scholarship to study in France. "There's nothing to keep the sound fran going straight up. There are no accoustics. You have to play really loud and that's a strain for 2\ or 3 hours."

Viogiani's group also had a bizarre experience one evening. "At the height of the day, our trio was playing on the street, and right across from us was another trio -- two flutes and a cello -- doing the exact same Haydn piece 'ie were doing. They were competing \Vith us. We'd do a movement, then they'd do a movement. The sounds began to meld and it didn't sound very good."

Then there are crowds. Teitelbaum once had ,stones thrown at him, while Grissom was doused with water at least five times. Kvo's experience was even more daunting: he ~~s playing his violin when a drunken man turned up and poured a bottle full of ciagrette ash onto the performer. Kvo lost his temper and pushed the man to the ground. The drunk responded by destroying the musician's amplifier. The incident shook Kvo up so much that he retired from street performing a month later.

There are also the good audiences. Valerie Naranjo remembers playing for a middle-aged group of people in front of the Metropolitan Museum who came to her defense when an irate man tried to have her removed. Grissan l'laS once dragged off the street by enthusiastic party-goers who brought him to a party (and paid him to be) a musical gift for the host. Anqther time, a woman pleaded with Grissom by long-distance telephone, insisting he come out to San Francisco -- at his own expense - to entertain guests at her home. And a Teitelbaum performance once touched a former miramba player so much that he asked if he could playa tune on Teitelbaum's instrument.

Page of original article.

Page of original article.

"I believe in the healing power of art, of music, of those kinds of things things that bring people together," say Naranjo. "The most concrete way I've been able to manifest that is in street performing. The end result is the audience is made much happier and I'm made much happier."

There are, of course, the Aaron Minskys of the 'iOrld -- the unhappy and unlucky street performers. A classical cellist by training, Minsky had heard' there ''laS good money in street performing. "A friend of mine had made $70 one afternoon," he recalls. "I was hard pressed for cash, so I took out my cello and played on the street for a whole afternoon. I made five dollars."

Another friend told him that he should go out with a quartet since most quartets maJ<, where he had heard people were more generous. They went. And played classical music, blues, and fi~ally, in disgust, a weird atonal improvisation. No one stopped, except for a long-haired , drugged-out man "no said, "You guys should be on television."

Minsky's spirits brightened when a young man who had been successfully selling ties nearby took pi ty on them and offered each of the quartet a free $10 tie. After he left, however, they found out that it had been a joke: the man had sold them children's ties. Nonetheless, the group put them on and continued playing their atonal improvisation until a passerby took a polaroid of the foursome. Minsky asked if he could keep it as a souvenir," he said to his friends. "That's a picture of the last time I played on the street." And it was.

"Street performing's not for everyone," says Grissom. "But it's important. When you're in school, you're given tools but you're not told how to get work. I found the street just offered a way to take the tools and do something with them. Adds Viogiani: "It's hard to get a job in an orchestra. Vacancies are only created when musicians retire or die. That's why I turned to this sort of music."

Most street performers hope to go on to bigger things. "I don't want to be 50 or 60 and say, 'Come on, kids, comer see granddad on the street. But a few feel like Robert Teitelbaum, who observes: "I have no desire to stop playing on the street. A lot of people are out there too be discovered. Not me. I want to do what I'm doing. If someone offered me a world tour, I'd turn it down. Unless it was a tour of street performing that is."

I WAS A STREET PERFORMER

If classical musicians are a rarity on the street, improvisational comedy groups are even more scarce, akin to an endangered species. I have the unique distinction of being in the only improv group to play successfully on those streets for over a year, and the only one to appear in the Village Voice's Festival of Street Entertainers in 1985. I got into it by accident. A writer and editor by trade, I began studying improvisation in 1981 to improve my writing skills. I liked it so much, hmiever, that I "laS soon performing with a six-person group in nightclubs around the city.

One evening, however, our club date was unexpectedly cancelled. The six of us were standing on the street when one of the group said, "Why don't we perform right here?" We did and within an hour iie had a crm,d of 50 or more watching us sing, dance, and perform comedy skits created fran their suggestions. In less than an hour we had made ovef $100.

After that, we iiere hooked. we more or less shunned the clubs and instead were on the streets, in the park, and an~1here outside we could find to perform. It was a thrill to have groups of 100 and 200 people watching us, and our 'work got better and better depending on the size of the audience.

We had our share of mishaps. Once a pair of drunken teenagers interrupted a show and joined in a skit. Another time, we were singing an improvised song \ihen a rain of ''later came pouring down on us from an apartment windOli above. We were drenched, but cheered up when our audience started yelling abuse at the person in the window.

And then there was the policeman who very politely asked us and our crowd of about 50 to move across the street because were blocking pedestrian traffic. We did - and like the children in the Pied Piper fairy story, the crowd happily followed us! We finally gave up the streets -- not because it became less fun but because it got too cold. But if you asked me what the most exciting creative work I ever did ,laS, I wouldn't hesitate in my reply: creating a crowd out of thin air.