Magazines 1980-1989

MEETING MY IDOLS – FOR FUN AND PROFIT

In the 1980s, I got the job that would define my career as an editor at Habitat magazine, a publication about co-ops and condos.It started with a handshake. In March 1982, I was all of 25 and I had been without a full-time job for a year or so. My first gig out of college had been at Firehouse magazine (1978-1981), where I learned all I ever wanted to know about the fire service industry. After two-and-a-half years on that job, first as assistant editor and then as associate editor, I had had enough. I left for a gig at Americana magazine – which started as a promising partnership and ended up a disaster. I left after six months – writing about firefighters was more my thing apparently than making rocking chairs seem interesting – and I took off for a year to write my first book, produce cable TV's Videosyncracies, and discover improvisation. And then I got my job at Habitat. While there, I wrote a great deal of freelance stories for various pulcications, and in the process, met a number of my childhood idols: Patrick McGoohan, Raymond Burr, the cast of Monty Python. And I got paid for it too! Nice work if you can get it and for a while, I did.

A Chorus Line

A CHORUS LINE

1985. Michael Douglas, Alyson Reed, Terrence Mann, Audrey Landers; dir. Richard Attenborough: 117m. (PC-13) Hi St D cc $79.95. LV $34.95. CED. Embassy. Image; excel.

If A Chorus Line is a play about faith, the overpowering, almost mythical belief actors have in their profession, then A Chorus Line: The Movie is an appalling demonstration of a director's lack of faith in his material. Granted, the show's story and structure have defeated many in the 10 years it took the musical to reach the screen. It is an intensely theatrical experience, a show in which actors, alone on a bare stage, reveal their loves, fears, and dreams to the voice of a faceless, offstage (and to them, omnipotent) director.

What's amazing is not the film's failure-artistic success would have been a surprise-but that it fails so miserably. Director Richard Attenborough evidently believed so little in the musical that he has junked its key elements. No longer a play about actors, it is now about two sophomoric lovers: the director, Zach (Michael Douglas), and chorus girl/dancer Cassie (Alyson Reed). The other actors' lives and monologues become fodder for the pair's fights and flashbacks.

Never has a director worked so hard against his material. Dance numbers are effectively obliterated by closeups, reaction shots, and jumpcuts. Backstage scenes, extraneous exteriors, and silly flashbacks open up the intense, intimate audition situation. The movie's style is wildly inconsistent, starting off cinema verite and then jarringly turning to highly stylized songs. And those songs: badly overdubbed and accelerated to a disco beat, they parody the originals, which were gritty, amusing, and simple. "What I Did for Love" has been given to Cassie, changing it from a moving actor's hymn to a trite lover's lament.

But that's par for the course in this predictable mishmash. It certainly says something that 10 years after seeing the play I can still remember moments and characters vividly. Ten minutes after this ended, all I could remember was how infuriatingly bad it was.

VIDEO, FEBRUARY 1988

A Dog's Life

For over 200 years, the dalmatian has been the firefighter's most faithful friend

By RAY PARKER (TOM SOTER)

"Bessie would always follow me into a burning building in the old days," recalled a Manhattan Fire lieutenant in 1916, "and stay one floor below the fighting line, as the rule required ... Bessie knew as much about the risks we ran as we did ...

"The companies that have been motorized find their dogs will not run ahead of the gasoline engines and trucks. They miss the horses and are afraid of the machine; .. I'm afraid she is the last of the mascots."

But the lieutenant was wrong. In 1976, Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois, firefighters held a graveside ceremony 'for Shadow, their ll-year-old dalmatian recently deceased, noting: "We dedicate this stone not to a dog, but to a friend of the firemen of the Arsenal." In 1978, the Fayetteville, Arkansas, department used Sparky, a four-year-old dalmatian as a prevention tool. In 1979, another Sparky, a three-year-old dalmatian, joined Los Angeles' Engine 103 on runs. And in 1980, Caesar, a 10-year-old dalmatian, walked out with the striking members of Chicago's Engine 22. When the city attempted to evict the dog from the firehouse, the men protested and won his case, calling him "a symbol of the firehouse."

The dalmatian is more than that. For 200 years, he has been a symbol of firefighters throughout the United States. At fires, at prevention activities, and in the firehouse itself, the spotted, sleek dog has been in theory and in fact the firefighter's most faithful friend.

That relationship developed because of another, earlier, friendship between dalmatians and horses. In 1940, Clyde E. Keeler and Harry C. Trimble, two _ Harvard University researchers, observed: "Dogs of the Dalmatian breed have definite differences with respect to the eagerness with which they follow horses and carriages. Since approximately 70 percent of the animals [we] tested chose those positions which entitled them to be rated as 'good' coaching dogs, it is evident that this is well entrenched in the breed."

Alfred and Esmeralda Treen in The Dalmatian (1980), put it more simply: "The dalmatian is built to run hard for long distances ... he is the only dog that was traditionally bred and trained to run with the horse-drawn vehicles. When he has the chance he is still delighted to go with the horses."

The dog's origin is less clear. The Treens report that a young 16th century Yugoslavian poet, Jurij Dalmatian, owned dogs that could have been dalmatians. "The interest in my Turkish-dogs grows in all Serbia," he said in a letter. "These dogs are so popular that they call them by my name-Dalmatian. This new name is already more and more ingrained."

A. Croxton Smith observed in 1931: "Attempts have been made, without being convincing, to divorce [the dogs] from their association with Dalmatia, the pre- War province of Austria bordering the eastern side of the Adriatic. One writer in 1843 endeavoured to show their connection with the Bengal Harrier, whatever that was .. .In the absence of any better evidence, I think we are safe in assuming that the breed did come from Dalmatia or neighboring regions."

Rowland Johns noted in Our Friend the Dalmatian (1933): "No one seems to know when the breed began. There was once a story that he was part tiger and came from Bengal. That was a pretty idea but a poor invention. Far more plausible was the idea that he lived in Denmark and worked for the peasants as a draught-dog, but that theory has not much value. The dog used in Denmark being the harlequin Great Great Dane, which, being also spotted, no doubt was confused with the Dalmatian ... The only thing we know is that he has always been called the Dalmatian and he probably came direct from that part of Southern Europe."

The dogs became known in continental Europe during the Middle Ages as they accompanied Gypsy caravans across the countryside. In addition to teaching the dogs tricks, the gypsies found that the animals were good guards. The dalmatians would stand watch over the horses by night and run with the wagons by day.

The practice was carried over to 17th century England where the dogs (called coach dogs) were used to guard stables. "A good Coach Dog has often saved his owner much valuable property by watching the carriage," wrote T.J. Woodcock in 1891.

"It is a trick of thieves who work in pairs for one to engage the coachman in conversation while the other sneaks around in the rear and steals whatever ... valuables he can .. .I never lost an article while the dogs were in charge, but was continually losing when the coachman was ... "

It was also fashionable to have a dalmatian running alongside or under a coach when on the road (coining the phrase "putting on the dog," meaning to do something as a show of wealth).

Observed Woodcock: "In training for the carriage, it is usually found necessary to tie a young dog in proper position, under the fore axles, for seven or eight drives before he will go as required. Some bright puppies, however, require little or no training, especially if they can be allowed to run with an old dog that is already trained."

In America, mention of the dalmatian can be found as early as 1787 when George Washington noted in a letter to his nephew: "At your aunt's request, a coach dog has been purchased and sent for the convenience and benefit of Madame Moose: her amorous fits should theretofore be attended to, that the end for which he is sent may not be defeated by her acceptance of the services of any other dog."

After work, dalmatians would often run alongside a trolley, following a firefighter home for a free meal. Noted one firefighter: "I got a street car pass for [our dog] and I guess she is ... the only dog in this city that could hop on and off a car without causing trouble ... She knew the right comer as well as I did and travelled the line alone if she missed me."

The Treens report that in 1910, "the Westminister Kennel Club offered a special class for Dalmatians, dogs and bitches, owned by members of the New York Fire Department. The results of the show indicate that first place was won by Mike [of Engine 81. .. Bess, owned by Lieutenant Wise [of Engine 39], was second. Smoke II, owned by Hook & Ladder No. 68, came in third ... "

With the switch to horseless carriages, the dalmatian disappeared from the firehouse--at least for a time. Kate Sanborn, in Educated Dogs Of Today (1916), writes: "For five and a halflong years Bessie cleared the

crossing at Third Avenue and Sixty-seventh Street for her company, barking a warning to surface-car motormen, truck drivers, and pedestrians, and during all that time she led the way in everyone of the average offorty runs a month made by No. 39. Then like a bolt from the sky the three white horses she loved were taken away, even the stalls were removed, and the next alarm found her bounding in front of a man-made thing that had no intelligence--a gasoline-driven engine. Bessie ran as far as Third Avenue, tucked her tail between her legs and returned to the engine house. Her heart was broken. She never ran to another fire."

The dogs disappeared, but firefighters missed them. During the 1930s and' 40s, mascots began to reappear in firehouses. While many kinds of animals were kept, including cats, monkeys, birds, dogs of other breeds, and even

a pig, firefighters seemed to gravitate toward their traditional mascot.

During the mid-1950s, dalmatians reached their height of popularity in the U.S., partly because of the Walt Disney film 101 Dalmatians. After the film, the breed soared in popularity, becoming a favorite among American dog owners.

With the revived popularity of the dog came the old stories of their intelligence and loyalty, as well as their ability to sniff out fires and perform heroic deeds. One dog, while hospitalized for laryngitis, tried to break out of his ward when he smelled a fire nearby. The commotion he raised helped uncover the fire. In Boston, during the Second World War, fire commpany dalmatians were trained for civil defense emergency service. They carried messages and Red Cross supplies and guarded property during and after air raids, as well as locating wounded persons under debris. In the late 1940s, one fire magazine reported that dalmatians were "again in the driver's seat."

But dog popularity changes. In 1976, the dalmatian was only 33rd on the American Kennel Club's new registrations list. Nonetheless, firefighters still enjoy the breed (see box), and dalmatians can now be found in firehouses throughout the country. Their special place with the firefighter is symbolized in New York's Greenwich Village. A painting on a firehouse door shows a fire engine racing to a blaze. Two firefighters are sitting in the front seat; between them is a friendly, speckled face, on its way to another fire. ~

ANOTHER SPARKY

Engine 44 in Manhattan is housed ina firehouse that is old-fashioned in ways other than appearance. Neighborhood residents bring cakes and cookies to the men on duty, children know the firefighters by name, and a frisky dalmatian called Sparky bounds around the station.

"We had another dalmatian before," says firefighter Frank Nolan. "He spent 15 years of service with us." When he died two years ago, a Long Island kennel donated a new dalmatian, six months old, to the bereaved company.

Sparky is very playful and makes "a lot of noise" when strangers come into the station house. He stays out of the way when the men are preparing for runs and remains in quarters when they're out.

"It took awhile," says Nolan, "but he seems to be getting engine-wise now. He's a bright dog." The junior man on duty takes him for his daily walks around the community.

"He gets us known," notes Nolan. "He's an asset to the firehouse. The children come in and give him a cookie. People come to see him. It's a nice rapport: he brings the neighborhood in. f They come to see the dog, not the firemen.”

New Dog, Old Tricks

Teaching a new dog old tricks is part of the job at the Fayetteville, Arkansas, Fire Department. For the past five years, the men of the "A" shift have used Sparky, a six-year-old, 50-pound dalmatian, to spread the fire prevention message. As trained by Lt. Larry Poage, Sparky demonstrates the dos and don'ts of fire safety to school children. A don't: Sparky stands up in the smoke. A do: Sparky crawls to safety by following the family escape plan.

"The lieutenant lectures and Sparky performs," says Fayetteville firefighter Dennis Ledbetter. "The children really like the show better than anything else we have tried." ~

Firehouse/July 1980

Ray Parker has written for Quarterly Shorts. This article was prepared with material supplied by Paula Reisenuiitz, Elaine Gewirtz, Dennis Ledbetter, and Collette Coyne

Art Schneider

ART SCHNEIDER

A Veteran Editor a Cut Above the Rest.

For Art Schneider, A.C.E., it was one of the most memorable moments in his life. Bob Hope was taping a 1965 comedy special.

on NBC and Schneider, Hope's videotape editor since the 1950s, was standing offstage when Hope called him out. "Most of you don't know what goes on behind the scenes during the editing of our show," began Hope. "We have a man in the basement ... who fixes all our mistakes, and we'd like to honor him tonight with the annual Bob Hope Show Crossed Scissors Award for Jump Cutting Above and Beyond the Call of Duty.

To many in the industry, Schneider has always been known as "Jump Cut," the editor's editor, racking up screen credits and awards almost since the beginning of television. As an NBC staff engineer from 1951 to 1968, Schneider edited over 500 variety shows, documentaries, music specials, series and news programs, winning four Emmys in the process. His work helped define the medium.

From the start, Schneider's modus operandi has been to edit quickly, efficiently and seamlessly. To improve video editing in the '50s-a cumbersome process, which involved the hand-splicing of tape-he worked with his colleagues at NBC to develop the first offline editing process as well as an early time-code system. As chief editor of the network's Rowan and Martin's Laugh-in in the late '60s, he was notorious for his organization and imagination.

"To edit Laugh-in, we had to adapt the technology to our concepts and not vice versa," says Laugh-in Creator and Producer George Schlatter. "At the time, video editing was primitive and considered a technician's job. Art helped change that. It became an artistic job."

Schneider's ambitions once lay elsewhere. When he was 18 and a model-airplane enthusiast, he entered the University of Southern California with the goal of becoming an aeronautical engineer. He explains, however, that he couldn't master the math required for the field. "I changed my major three times before I finally settled on cinema studies," he recalls. "There's not much math in that."

Schneider soon found he had a knack for cutting film, and it was during his senior year that a professor introduced him to an NBC executive searching for a film editor. "The job they offered was simple-editing leaders onto kinescopesbut they didn't want to spend the time training beginners how to edit," recalls Schneider. "They wanted someone who already knew how to do it."

A four-hour job interview led to what would be a 17-year career at the network. Although eventually he became the network's supervising editor, he began as a "Group 2 Engineer" -handsplicing videotape and film, and operating kinescope machines and camerasbecause the term "editor" was not officially sanctioned by NBC until the '60s.

Schneider worked constantly, averaging 40 to 50 shows a year and racking up such credits as 51 Bob Hope shows, three critically acclaimed Fred Astaire programs, and specials starring Judy Garland, Pat Boone, Milton Berle and Jack Benny. "My USC training in cinema really helped," he says-particularly for specials, "which were tricky. You couldn't just grind them out like [you might on a] series. The star wanted to put the best foot forward."

In 1967, Schlatter, a former colleague from NBC's Colgate Comedy Hour, apI proached him with the Laugh-in pilot. "I thought it had a funny name and a pretty thick script," Schneider recalls, "but I said, 'Fine, I'll do it.' " The script was thickfour inches, to be exactand, at a time when 80 edits an hour for video was considered excessively complicated, Laugh-in weighed in at about 400. "It was a gargantuan task," says Schlatter, "and Laugh-in may have been the first show on TV whose editor was recognized for the contribution he brought to the whole."

With its quick blackouts, short sketches and zany music pieces, Laugh-in was an editor's nightmare. Schneider, with Schlatter at his side, spent three weeks of 20-hour-a-day edits to produce the pilot. "At the end of the first assembly [which took five days], George didn't like what he saw. He sat back and cried, 'What have I wrought?' " recalls Schneider, who wound up recutting the program five times. "After the fifth, George was satisfied, but I was still bothered by something that didn't quite click. I couldn't sleep, thinking about it." Then, as he lay in bed, he had an inspiration:

He would add a tag scene after the closing credits-a discarded piece of footage of Arte Johnson as a Nazi saying, "Verrrry interesting." Not only did Schlatter love the touch, the bit became a catchphrase of the series.

In 1968, Schneider left NBC to form, with Schlatter, Burbank Film Editing (where he continued to work on Laughin). Schneider left in 1970 to work at CFI, where he stayed until 1976 and helped develop the first CMX 300 on-line editing system. From there he freelanced on a variety of projects, including off-net hours for syndication and documentaries on pollution. In addition, he served on the board of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences; became a member of the SMPTE education committee; and began writing (over 50 articles) and lecturing on his profession.

Although recently semi-retired, the 59year-old editor is keeping busy. In March, for example, Focal Press published Electronic Postproduction and Videotape Editing, Schneider's history of and guide to working the TV editing business. And he is currently writing a new book, A Dictionary of Postproduction Terms.

"To be successful," Schneider concludes, "you have to be very, very dedicated. And you have to work your butt off."

WRAP, September/October 1989

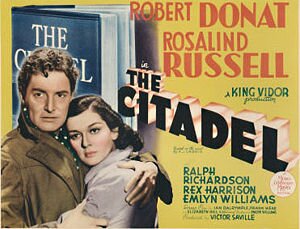

Books Into Movies

Over the past fifty years, many techniques have been used to adapt blockbuster books for the screen. While some approaches to this formidable task have pitted the original author against the screenwriter, all of the following techniques have resulted in great movies.

Over the past fifty years, many techniques have been used to adapt blockbuster books for the screen. While some approaches to this formidable task have pitted the original author against the screenwriter, all of the following techniques have resulted in great movies.

THE "I DON'T LIKE YOUR POLITICS" APPROACH

This tack was best summed up by Adolph Zukor, figurehead chairman of the board of Paramount during the 1940s. When asked about Paramount's version of For Whom the Bell Tolls, an intense Hemingway novel with a provocative political backdrop, he replied, "It is a great picture, without political significance. We "are not for or against anybody"

Another example is John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, a book meant by its author "to rip the reader's nerves to rags. I don't want him satisfied." Though the novel attacked capitalism, the film was a softened version of Steinbeck's original ideas. Interestingly director John Ford, who won an Academy Award for his efforts, did not read the book.

Bernard Malamud's The Natural, about baseball player Roy Hobbs, a man who destroys himself, became a story about Roy Hobbs, a man who overcomes the beast in himself. At the end of Malamud's novel, Hobbs strikes out causing his team to lose the World Series; but in the film, Hobbs hits a grand slam homerun, saving his team and the Series. As one of the adapters, Roger Towne, explained, "The duties of a screenwriter are not just as a technician to adapt a book. In large part, they are to reflect the attitude of his time. Malamud wrote the tale on Roy Hobbs [coming out of the attitude formed by that terrible calamity of World War II, [so] you can understand why the fates would conspire to bring a good man down. From the vantage point of 1984, in nuclear shadow, I'm writing about the ability of man to overcome defeat. I would love to keep the vision of man's perfectibility alive."

THE "I KNOW WHAT YOU MEANT EVEN IF YOU DON'T" APPROACH

Blade Runner, based on Philip K. Dick's Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? took ten years and a half-dozen adaptations to reach the screen. In the process, it went from cautionary tale to slapstick comedy to science-fiction film noir Dick, who frequently fought with director Ridley Scott once observed, "Scott's attitude was quite a divergence from my original point of view since the theme of my book is that [the hero] is dehumanized through tracking down the androids. When I told him this, Scott said that he considered it an intellectual idea, and added that he was not interested in making an esoteric film."

Yet often the director does know best in translating ideas from one medium to the other. Milos Forman's version of Ken Kesey;s One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest took a metaphorical novel of highly stylized characters and ideas and turned it into a drama about people. Although Kesey blasted the movie without seeing it, Forman defended his changes, "In film, the sky is real, the grass is real, the tree is real; the people had better be real, too."

THE "FORGET THE BOOK I LIKE THE TITLE" APPROACH

Director Howard Hawks once bragged to Ernest Hemingway "I can make a picture out of your worst story ... that piece of junk called To Have and Have Not." Hawks made a good movie, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, but he did it by ignoring the book and remaking Casablanca.

Woody Allen pulled the same trick (although more blatantly) with Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex, which uses Dr David Reuben's question-and-answer sex manual as the starting point for a series of comic sketches. The question, "How Accurate Are the Findings of Sex Clinics?", for example, is answered with a silly fifteen-minute story about a mad sex doctor who studies sexual functioning in hippopotamuses.

THE "NON-FICTION FICTION" APPROACH

This involves taking a true story and making it into a "fictionalized" movie. Screenwriter William Goldman once explained his problems in adapting Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein's All the President's Men. The Watergate cover-up story into a film: "Great liberties could not be taken with the material. Not Just for legal reasons, which were potentially enormous. But if there was ever a movie that had to be authentic. it was this one..... We were dealing here with probably the greatest triumph of the print media in many years, and every media person who would see the film would have spent time at some point in their careers in a newspaper... We had to be dead on, or we were dead."

Screenwriter Goldman was dealing with a book with no dramatic structure, little dialogue, hundreds of names, places, and facts, and an outcome – President Nixon's downfall – that was known at the outset. He handled these handicaps by throwing away half the book and focusing on thirteen key events in the story.

THE "LET'S BE LOGICAL" APPROACH

This is best exemplified by Goldfinger, the third and the best of the James Bond movies. The Ian Fleming novel finds criminal Auric Goldfinger planning to rob Fort Knox. As coscreenwriter Richard Maibaum observed, "Fleming never bothered his head about how long it would take to transport $16 billion worth of stolen gold bullion or how many men and vehicles would be required. Obviously. it would take weeks, hundreds of trucks, and hundreds of men." Maibaum and partner Paul Dehn improved on this by having Goldfinger plan to contaminate the gold (and thereby increase the value of his hoard). They also improved on the book by eliminating coincidences, improbabilities, and the most hackneyed cliche of the story, Bond being menaced by a buzz saw (it was replaced by a laser beam).

THE "LESS IS MORE" APPROACH

A prime example of this is The World According to Garp. an incredibly convoluted, picaresque novel, loaded·with subplots and digressions. The screenwriters pruned it down to its essentials, retaining much of the flavor if not the detail of the book.

THE "METAPHOR THAT WASN'T THERE" APPROACH

In this technique, an adapter takes a simple story and makes it into a "Meaningful Story." The best example is the film Greystoke. The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, which transforms Edgar Rice Burroughs' jungle superman into a symbol of natural man destroyed by civilization. Earlier Tarzan movies, such as the 1918 Tarzan of the Apes and the 1932 Tarzan the Ape Man, employed the same material without the metaphors.

Whatever the approach used by producers and screenwriters, the final word comes from fans of these great films and the fans have spoken by making their favorites among the best-selling and the best-renting home video entertainment.

VIDEOGRAPHY

THE AFRICAN QUEEN (1951), C, Director: John Huston. Book: CS Forester. Screenplay: James Agee and John Huston. With Katharine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart CBS/Fox.

ALL THE PRESIDENT'S MEN (1976), C, Director: Alan J. Pakula. Book: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. Screenplay: William Goldman. With Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. Warner.

THE ANDERSON TAPES (1971), C, Director: Sidney Lumet Book: Lawrence Sanders. Screenplay: Frank R. Pierson. With Sean Connery and Dyan Cannon. RCAI Columbia.

BEN-HUR (1959), C, Director: William Wyler. Book: Lew Wallace. Screenplay: Karl Tunberg. With Charlton Heston, Jack Hawkins, and Stephen Boyd. MGM/UA.

BLADE RUNNER (1982), C, Director: Ridley Scott. Book: Philip K. Dick. Screenplay: Hampton Fancher and David Peoples. With Harrison Ford and Rutger Hauer. Ernbassy. -

EAST OF EDEN (1955), C, Director Elia Kazan. Book: John Steinbeck. Screenplay: Paul Osborn. With James Dean, Julie Harris, and Jo Van Fleet. Warner

EVERYTHING YOU ALWAYS WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT SEX (1972), C, Director: Woody Allen. Book: Dr. David Reuben. Screenplay: With Woody Allen, John Carradine, and Lou Jacobi. CBS/ Fox.

THE EXORCIST (1973), C, Director: William Friedkin. Book and Screenplay: Wil· liam Peter Blatty. With Ellen Burstyn, Max Von Sydow, and Linda Blair. Warner.

THE GODFATHER (J972), C, Director Francis Ford Coppola. Book: Mario Puzo. Screenplay: Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo. With Marlon Brando, AI Pacino, and James Caan. Paramount.

THE GODFATHER, PART" (1974), C, Director: Francis Ford Coppola. Book: Mario Puzo. Screenplay: Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo. With AI Pacino, Robert Duvall, and Robert De Niro. Paramount.

GOLDFINGER (1964), C, Director: Guy Hamilton. Book: Ian Fleming. Screenplay: Richard Maibaum and Paul Dehn. With Sean Connery. Gert Frobe. and Honor Blackman. CBS/Fox.

GONE WITH THE WIND (1939), C, Director: Victor Fleming Book: Margaret Mitchell. Screenplay: Sidney Howard. With Vivief'l Leigh, Clark Gable, Olivia de Havilland, and Leslie Howard. MGM/UA.

THE GRAPES OF WRATH (1940), B/W, Director: John Ford. Book: John Steinbeck. Screenplay: Nunnally Johnson. With Henry Fonda, Jane Darwe!/. and John Carradine. CBS/Fox.

GREYSTOKE: THE LEGEND OF TARZAN, LORD OF THE APES (1984), C, Director: Hugh Hudson. Book; Edgar Rice Burroughs. Screenplay: P.H. Vazak (Robert Towne) and Michael Austin. With Christopher Lambert. Andie McDowell, and Ian Holm. Warner.

IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT (1967), C, Director: Norman Jewison. Book: John Dudley Ball. Screenplay: Stirling Silliphant. With Sidney Poitier. Rod Steiger, and Warren Oates. CBS/Fox.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1166:]]

JAWS (1975), C. Director: Steven Spielberg. Book: Peter Benchley Screenplay: Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb. With Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss. MCA.

THE JEWEL IN THE CROWN (1984), C, Director: Christopher Morahan and Jim O'Brien. Book: Paul Scott. Screenplay: Ken Taylor With Peggy Ashcroft. Eric Porter, and Tim Piggott-Smith. Simon and Schuster.

THE LAUGHING POLICEMAN (1974), C, Director: Stuart Rosenberg, Book: Thomas Rickman. Screenplay: MaJ Sjowall and Per Wahloo. With Walter Matthau, Bruce Dern, and Lou Gossett. Key.

LOVE STORY (1970). C, Director: Arthur Hiller. Book and Screenplay: Erich Segal. With Ali MacGraw. Ryan O'Nea', and Ray Milland. Paramount.

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1935), B/W, Director Frank Lloyd. Book: Charles Nordhoff and James Hall. Screenplay: Talbot Jennings and Jules Furthman. With Charles Laughton, Clark Gable, and Franchot Tone. MGM/UA

MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1962), C, Director: Lewis Milestone. Book: Charles Nordhoff and James Hall. Screenplay: Charles Lederer With Marlon Brando, Trevor Howard, and Richard Harris. MGM/UA

THE NATURAL (1984), C, Director Barry Levinson. Book: Bernard Malamud. Screenplay: Roger Towne and Phil Dusenberry With Robert Redford and Robert Duvall. RCA/Columbia

OF MICE AND MEN (1939), B/W, Director: Lewis Milestone. Book: John Steinbeck. Screenplay: Eugene Solow With Lon Chaney Jr and Burgess Meredith. Prism.

ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST (1975), C, Director: Milos Forman. Book: Ken Kesey Screenplay: Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman. With Jack Nicholson, Louise Fletcher, and Brad Dourif. HBO/Cannon

A PASSAGE TO INDIA (1984), C, Director David Lean. Book: E.M. Forster Screenplay: David Lean. With Judy Davis, Victor Banerjee. and Peggy Ashcroft. RCAI Columbia.

PSYCHO (1960), B/W, Director: Alfred Hitchcock. Book: Robert Bloch. Screenplay: Joseph Stefano With Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh. MCA,

PRIZZI'S HONOR (1985), C, Director: John Huston. Book: Richard Condon. Screenplay: Richard Condon and Janet Roach. With Jack Nicholson, Kathleen Turner, and Anjelica Huston. Vestron

THE RIGHT STUFF (1983), C, Director Philip Kaufman. Book: Tom Wolfe. Screenplay: Philip Kaufman With Sam Shepard, Scott Glenn, and Ed Harris. Warner.

SEVEN DAYS IN MAY (1964), B/W, Director: John Frankenheimer. Book: Fletcher Knebel. Screenplay: Rod Serling. With Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, and Ava Gardner. Paramount.

TERMS OF ENDEARMENT (1983), C, Director: James L. Brooks. Book: Larry McMurtry Screenplay: James L. Brooks. With Shirley MacLaine, Debra Winger, and Jack Nicholson. Paramount.

THE THIN MAN (1934), B/W, Director: WS Van Dyke II. Book: Dashiell Hammett Screenplay: Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett. With William Powell, Myrna Loy and Maureen O'Sullivan. MGM/UA.

TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT (1944), B/W, Director: Howard Hawks. Book: Ernest Hemingway Screenplay: Jules Furthman and William Faulkner With Humphrey Bogart, Walter Brennan, and Lauren Bacall. MGM/UA.

THE WIZARD OF OZ (1939), B/W and C, Director Victor Fleming. Book: L. Frank Baum. Screenplay: Noel Langley and Florence Ryerson. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, and Margaret Hamilton. MGM/UA.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GARP (1982), C, Director: George Roy Hill. Book: John Irving. Screenplay: Steve Tesich. With Robin Williams, Mary Beth Hurt, and Glenn Close. Warner.

WUTHERING HEIGHTS (1939), B/W, Director: William Wyler Book: Emily Bronte. Screenplay: Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. With Merle Oberon, Laurence Olivier, and David Niven. Embassy.

Gone With the Wind. David O. Selznick’s marvelous three and one half hour version of Margaret Mitchell’s Pulitzer Prize winner was one of the most eagerly awaited motion pictures of 1939. Not only that, it set new standards for filmmaking techniques and fidelity to text. Until Gone With the Wind, adaptations of books were in most cases only marginally faithful to their sources. (In fact, Mitchell received hundreds of letters from fans asking her to prevent the filmmakers from “changing the story as they always do in Hollywood.”) Selznick was so scrupulous that 17 different writers worked on the picture at different times, condensing its mammoth plot – approximately 150 characters were reduced to around 50; heroine Scarlett O’Hara’s three children became one; the Ku Klux Klan disappeared. The movie is a successful rendering of the essence of the novel – a super-soap-opera about the trials of Scarlett, whose rise and fall and rise again corresponds with the fortunes of the Old South. And whether you read the book (over 1,000 pages) or see the movie, it’s a long, wonderful experience.

The Godfather. This movie and its sequel, The Godfather, Part II, are brilliant transformations of a simple crime novel. Mario Puzo wrote the book in 1970 and collaborated with director Francis Ford Coppola on the screenplay, using the story of Vito Corleone, the Mafia Godfather, as a metaphor for the American success story. The book is fast-paced, uninspired melodrama; the film aims for much more. The story is of one immigrant family's rise and fall, as familial love disappears in the face violence.

The African Queen is essentially a three-character story about a man, a woman, and a boat. The man is Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart), a gin-soaked riverboat captain in World War I Africa. The woman is Rose Sayer (Katharine Hepburn), a missionary And the boat is The African Queen, a steam-engine launch that Allnut and Sayer pilot in a mad quest to sink a German warship. Their odyssey pitting them against white-water rapids, leeches, and nasty Germans, is propelled by wonderful comic performances and a clever script that considerably improves on C.S. Forester's overly serious novel. "To be faithful to the author," noted director/adapter John Huston, "sometimes means changing the author." In the case of The African Queen, the changes are right on target.

The Thin Man was a surprise hit in its day. Filmed in two weeks in 1934, it paired witty William Powell with ravishing Myrna Loy in what became the Thin Man entries. Based on Dashiell Hammett's novel, it was also a first for American cinema: a screwball comedy/ mystery that introduced Hammett's boozing, wisecracking, husband-and-wife sleuths, who were supposedly based on the author himself and Lillian Hellman. The script and dialogue made chanqes in the book's characterizations (the wife, Nora, changed from a tough cookie to a world-wise innocent, while the husband, Nick, changed from a fast-talking gumshoe to a silghtly inebriated amateur detective), which were overall improvements. The Powell-Loy exchanges are witty and the movie is a pure delight.

Ben-Hur. The epitome of the epic film, Ben-Hur woneleven Oscars and has been called the "thinking man's epic" It's not hard to see why. Based on a sprawling book by Lew Wallace, Ben-Hut is the story of friendship betrayed, of revenge sought and won. It is the story of Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and his boyhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd), who feud and eventually fight to the death in a justly famed chariot race. Like the novel, the movie is packed with events, but the focus is always on the theme of becoming what you hate. Heston deservedly won an Academy Award for his complex portrait of a flawed, driven man.

Wuthering Heights, This beautifully photographed version of Emily Bronte's gothic classic pares down the three-generational plot of the original and concentrates instead on the tragic love affair of Heathcliff (Laurence Olivier) and Cathy (Merle Oberon). It was Olivier's first major American film, and it made him a star. His brooding presence gives the movie much of its passion and pathos – he says as much with a look as Bronte manages with pages and pages of speeches. The movie is helped tremendously by effectively sentimental dialogue: “Be with me always. Drive me mad. Only do not leave me in this dark alone where I cannot find you. I cannot live without my life. I cannot live without my soul.” We dare you not to cry at this ultimate tearjerker.

The Jewel in the Crown

Based on Paul Scott's four-volume Raj Quartet, this 14-part British TV series restructured the original story but is otherwise a brilliantly faithful adaptation. It is the tale of England's passion for India and of one Indian man’s love for a white woman. It is also a tale of rape, religion, sadism, and independence, featuring a vivid collection of characters who will move you with their loves, their hates, and their deaths. The writing, the performances, and direction are all superb, and if India was the “jewel” of the British Empire, The Jewel in the Crown is the gem in Granada Television’s collection.

VIDEO TIMES/March 1987

Chimney Sweeps

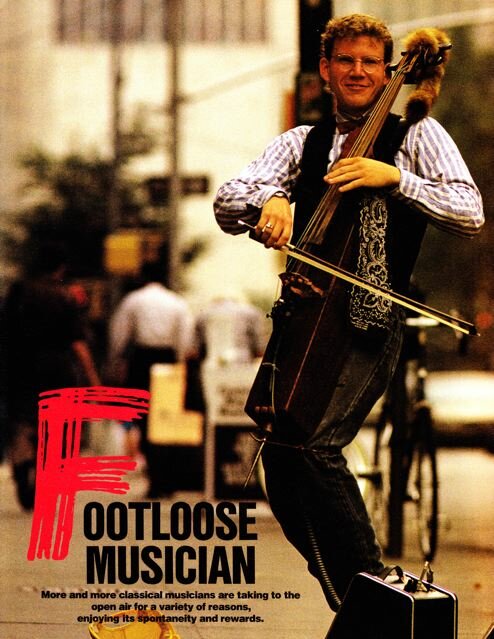

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1457:]]

As fall turns to winter, Harry Richart's phone rings off the hook. Richard Nixon, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and Bette Midler, among others, begin calling for help. "The cold season is the heating season," says Richart. "That's the best time for me."

Harry Richart is a chimney sweep. For twenty-two years he has cleaned chimneys, restored old fireplaces, and instructed others on the safety techniques involved in burning solid fuel.

Although the extent of Richart's work is unusual (he owns his own chimneycleaning company), his devotion to the profession of chimney sweeping is not. The 600-member National Chimney Sweep Guild estimates that there are several thousand sweeps, both full-time and part-time, in the United States-including mailmen, ironworkers, firemen, plumbers, and housewives. A Philadelphia sailor cleans chimneys on his Navy base, while a Tulsa, Oklahoma, college student left marketing to work in fireplace flues.

"The energy crisis got people interested in heating with wood and coal," says Richart. "And that built up a need for sweeps. "

The Winter Flue

When wood burns, it leaves deposits of creosote, an inflammable substance caused by the condensation of volatile gases. If it is not removed, creosote can block the chimney flue and constitute a fire hazard. "I had a case where an eight-inch round chimney was plugged up six feet solid with creosote," Richart recalls. "It's a miracle it didn't burn the house down."

In colonial America, creosote was frequently removed by setting the chimney itself on fire, an approach that often destroyed the house in the process. Another method involved tying a rope around a white goose's leg and lowering the bird down a stack. Its flapping wings would dislodge the creosote, and the blacker the bird became, the cleaner the chimney.

When these methods proved particularly ineffective, the idea of using chimney sweeps was imported from England. English sweeps began working in the late sixteenth century, when dirty chimney flues resulted in a record number of fires. The early sweeps climbed and cleaned most two-by-three-foot stacks. However, the proliferation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of zigzagged, narrower chimneys built to heat taller buildings more effectively forced sweeps to employ very young "climbing boys" as workers. The high number of smoke- or fire-related deaths among these children led to the outlawing of their use in the mid-nineteenth century.

To replace the boys, sweeps developed more complicated tools. William Hall's patented 1820 sweeping machine, made of hollow rods and cane bent to the shape of the narrowly angled London flues, employed a brush and malleable whalebone spikes. The sweep stood in the fireplace and extended the long rod up the chimney. In the 1850s, an American added a wheel to the brush, which was hand-turned and later motorized.

Sweeps Get The Squeeze

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1458:]]

In Europe, sweeps considered themselves professionals, establishing apprentice systems and guilds to regulate the business. In America, however, the trade was first considered highly disreputable.

Typical sweeps, described by historian Ceorge Phillips in The American Chimney Sweeps, were "garbed in the tawdry. sartorial splendor of ill-fitting, frayed frock coats, baggy, often patched striped trousers, and battered silk hats perched rakishly on their woolly polls .... "

The introduction of gas heating in the twentieth century seemed to mark the end of the trade in America, at least, as more and more sweeps went unemployed.

But renewed interest in solid fuel revived the industry; many younger men joined the ranks of those veterans, such as Harry Richart, who had continued operations even during the lean oil-andgas days. Most of the newcomers have been trained on the job by veteran sweeps or else have gained their knowledge from such chimney-sweeping schools as August West in Connecticut or Black Magic in Vermont.

Climbing The Ladder

Apprentice sweeps learn how to employ wire or soft brushes, a metal scraper, and a hammer and chisel to remove creosote, and they are often instructed in the use of motorized cleaning equipment, such as a high-volume, compact vacuum cleaner that removes 700 cubic feet of air per minute.

Often the sweeps learn their trade from their fathers, since sweeping is traditionally a family affair. Richart's two sons have been sweeps since they were old enough to climb a roof and are now fully qualified workers. For forty years, another sweep in Newark, New Jersey, has owned the business that he inherited from his father, who had owned it for fifteen. There are a number of husband and wife teams. Mary Ann and Gary Beaufait of South Carolina are both sweeps, and their son is in training.

"There's no such thing as a sweep who puts on a hat and starts sweeping chimneys," says Richart. "You can't do it without experience. Every day I go out on the road, I find problems I never came across before."

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1460:]]

Soot, Alors

Richart's TriState Chimney Sweeping Company operates four trucks, manned by a sweep and a "helper," which cover New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Like most successful sweeps, his people average seven or eight cleanings per truck a day at about $45 per cleaning. TriState conducts a free chimney inspection with each cleaning, checking for cracks and loose bricks, and also offers renovation and restoration services at extra cost.

This last service is not typical of sweeps, but it is one of the elements that allow Richart to keep operating year round. "Sweeping is a seasonal business," he explains. "Most new sweeps start in the winter and say, 'My God, look at the money I'm making.' But they forget about those five months they're doing nothing and can't pay the bills."

Established sweeps usually maintain lists of regular customers, send out notices reminding them that a chimney checkup is needed, make an appointment, and come by to inspect the chimney.

"If it's very dirty when we clean it," says Richart, "we make a note to come back in a month and a half and see what it looks like then. "

A Safety Checklist

The amount of use a fireplace or furnace receives determines the frequency of the visits, although according to chimney sweep Mark Swann, president of Top Hat Sweeps, home owners should request more frequent inspections in the following situations:

One-story chimneys. These don't draw as well as higher chimneys and can dangerously malfunction.

Airtight buildings. The chimneys may not draw properly.

Chimneys on the outside walls of houses. These may not become warm enough to draw correctly,

Wood stoves. The pipe connecting the stove to the chimney may need to be cleaned every two weeks, a task that a sweep can teach a home owner.

Old chimneys. Although they smoke' less and give off more heat than modern chimneys, their general lack of ceramic flue liners makes them more dangerous. They should be swept often.

A chimney should be cleaned at least, once a year, and if the home owner is using an airtight stove, twice-yearly cleanings would be in order. Use older, hard wood; green (young) wood produces a great deal of smoke and creosote.

"The key to chimney safety is education," notes Richart, who, as a member of the board of directors of the five-yearold National Chimney Sweep Guild, hopes to increase the professionalism of sweeps and the safety of home owners.

The guild set up a chimney-sweep certification test, which resulted in the certification of 242 swpeps. It is currently working with the Fire Trade Center and the Office of Consumer Affairs in Washington, D. C., to improve federal laws regulating the use of wood-burning stoves.

"People try to cut corners," says Richart, a certified fire inspector. "Instead of cutting the draft in a stove down to a quarter of an inch, as the operating manual instructs, they say, 'Mine burns better when it's open all the way.' But they don't realize that now they're feeding more oxygen into that stove chimney and it's going to have a creosote buildup." If the instructions are unclear, or if you're using an old fireplace, the guild suggests that you indeed call a sweep.

The guild is also planning to conduct a series of fire-safety seminars around the country. In addition, it hopes to set up the sort of training system that exists in Europe, where a sweep works as an apprentice, then asweep, then a master chimney sweep. "A chimney sweep over there is well respected," Richart notes.

Miles To Go Before We Sweep

Possibly because it detracts from that professionalism, the sweep's traditional Dickensian costume-black top hat and tails-is mostly eschewed by older sweeps unless it is specifically requested.

"Sweeps have come a long way," remarks Richart. "But we still have a long way to go and a lot to do. Our main concern is safety. We educate and we clean. And that's important because so many houses are going to the ground on account of poor installation and dirty chimneys. " •

DIVERSION JANUARY 1982

Christmas Movies

The Spirit of Christmas Past

Ever-popular holiday movies and specials are back on the box this year.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:451:]]

Holiday spirit or holiday humbug? Charles Dickens enjoyed writing Christmas stories that fairly vibrate with good cheer, sentiment, and warmth. His contemporary, Anthony Trollope, thought such tales were a cynical exploitation of the season. No matter who was right, the equivalent of the Victorian Christmas story is still intact and is on the air today. Christmas-oriented movies and specials and holiday episodes of regular series appear throughout December-many rerun from past years and all emphasizing love, harmony, and the importance of relating to others.

If past practices are followed, the movies and TV programs that will be shown this season should include most of the ones in the following list. Although there will be some new programming, stations prefer the traditional 'because, says one observer, "people like to anticipate these specials. There are so few things they are sure of these days."

A Christmas Carol. Perhaps Charles Dickens' most popular story, his 1843 A Christmas Carol has been the basis of countless movie and television? adaptations, most of which invariably tum up on the tube during Christmas week., Among theatrical films, there is a 1935 British version called Scrooge, a 1938 MGM film starring Reginald Owen, a 1951 adaptation with Alistair Sim (generally considered the best), and a 1970 musicaJ (also titled Scrooge) with Albert Finney singing Leslie Bricusesongs. A 1979 made-for- TV movie called An American Christmas Carol updates the story to 1933, casting Henry[[wysiwyg_imageupload:452:]] "The Fonz" Winkler as a New England version of Scrooge. Jim Backus's Mr. Magoo and the voice of Walter Matthau are featured in two cartoons, Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol and The Stingiest Man in Town. (Matthau is Scrooge, and a non-Dickensian figure, B.A.H. Humbug, narrates.) A puppet version, also called A Christmas Carol, is frequently shown on the networks or public television. And finally, such comedy series as The Odd Couple, Bewitched, The Honeymooners, and WKRP in Cincin nati have produced Christmas Carol stories in which the program principals take on the roles of Scrooge, the ghosts, and Bob Cratc·hit.

Miracle on 34th Street. The best of the Christmas goodwill movies, Miracle on 34th Street (1947), is show'n every year'on local stations during the' holidays. This amusing story about a Macy's Santa Claus who must' prove in court that he is the real Kris Kringle won Academy and Golden Globe awards for writer-director -George Seaton and for Edmund Gwenn, who plays Santa with just the right amount of naivete, charm, and worldly wisdom. Co-starring Maureen O'Hara, John Payne, and a young Natalie Wood (as the girl who doesn't believe in Santa Claus until the end), the film delivers a message that never gets sentimental-to trust and believe in people. Although it ~as remade in 1973 with Jane Alexander, David Hartman (now host' of Good Morning America), and Sebastian Cabot, the 1947 version still remains the favorite.- (A 1977 TV Guide poll ranked it number 9 in a list of the 13 most popular movies on TV; Casablanca and King Kong headed the list.)

March of the Wooden Soldiers. Originally titled Babes in Toyland (but renamed to avoid confusion with the 1961 Walt Disney movie), this 1934 film was among Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy's most financially successful efforts and the most ambitious project undertaken by their producer, Hal Roach. Casting Laurel as Stanley Dum and Hardy as Oliver Dee (characters who incorporated attributes of Mother Goose's Simple Simon and the Pieman), two employees of a cantankerous Santa Claus in a Toyland populated by human-size mice, pigs, and rabbits, Roach and his collaborators completely discarded most of the Victor Herbert operetta on which Babes was ostensibly based, keeping only some of the score. As one critic pointed out, Roach combined "elements of Mother Goose with the hoariest of screen villains, the heartless landlord, and bogeymen straight from the Brothers Grimm." The movie was a critical success as well, with critic Andre Sennwald, in the December 13, 1934, issue [[wysiwyg_imageupload:453:]]of The New York Times, calling it "authentic children's entertainment and quite the merriest of its kind." In 1954 NBC produced its own version with Wally Cox and Today show host Dave Garroway. Disney's version featured Ray Bolger and two Laurel and Hardy imitators.

Great Expectations. Although Dickens' great book has almost nothing to do with Christmas, apparently TV programmers find its Victorian flavor especially appropriate, because various film adaptations appear regularly this time of year. Although adaptations of the novel were made in 1934 and 1974, most stations prefer to broadcast the superlative 1946 David Lean version. Dickens' story of a young boy, Pip, brought up with "great expectations" of love and money, is a romantic tale of disillusionment and mystery. Noted Gerald Pratley in The Cinema of David Lean: "What Olivier has done for Shakespeare on the screen, Lean has done for Dickens." Great Expectations is perhaps the most effective translation of novel into movie ever made, the first adaptation of a Dickens story to masterfully capture the flavor of a novelist many claim to be well suited for the screen. Although Lean and his cowriters pared and edited the mammoth 1861 novel, they retained the right scenes and characters to capture the spirit of the story. Here is the convict Magwitch (Finlay Currie) confronting the young Pip (Anthony Wager) on the desolate moors. Here is Miss Havisham (Martita Hunt) in her decaying mansion, Satis House, plotting revenge on the world. Here is Jaggers (Francis L. Sullivan, repeating his role from the 1934 version), the imperious lawyer only interested in "facts, facts, facts." And here are Alec Guiness (in his first film role), John Mills, Valerie Hobson, and Jean Simmons brilliantly bringing life to Dickens' gallery of unforgettable characters. Great Expectations earned a place on The New York Times' list of "10 Best Films" of 1947, Academy Award nominations for best picture and director, and awards for cinematography, art direction, and set decoration.

A Crosby Christmas. Almost as much as Santa Claus and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Bing Crosby came to epitomize the Christmas spirit, through songs such as "White Christmas" and his holiday TV specials. He also appeared in four very popular Christmas movies. Holiday Inn (1942), [[wysiwyg_imageupload:454:]]co-starring Fred Astaire, was the comedy in which he first sang "White Christmas," later reprising it in the 1954 movie named after the song. "It's a great song with a simple melody," he said in his autobiography, "and nowadays anywhere I go I have to sing it. It's as much a part of me as 'When the Blue of the Night' or my floppy ears." Despite the song's popularity, Going My Way (1944) is generally considered his best film. As Father Chuck O'Malley, a boyish priest who teaches the crusty Father Fitzgibbon (Barry Fitzgerald) how to cope with life, Crosby earned an Academy Award (he repeated the role in The Bells of St. Mary's, another Yuletide favorite, opposite Ingrid' Bergman). The movie also won Academy Awards for Fitzgerald and writer-director Leo McCarey, and a Golden Globe as best picture. It also inspired a short-lived 1963 TV series starring Gene Kelly and Leo G. Carroll.

It's a Wonderful Life. Frank Capra's movies, although "Capra corn" to some, epitomize the Christmas spirit. In Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and Meet John Doe (1941), Capra trumpeted human virtues in sentimental stories of Americana. It's a Wonderful Life, made in 1946, was his most whimsical, a "Christmas Carol" tale reaffirming the common man's essential goodness. The movie, Capra's first postwar effort for his own company, Liberty Films, was based on "The Greatest Gift," by Philip Van Doren Stern, a short story written for a Christmas card. Dalton Trumbo and Clifford Odets had worked on the screenplay for another producer, but when Capra bought the property (for $50,000), he used other writers and concocted scenes of his own. The movie tells the story of George Bailey (James Stewart), a would-be suicide who believes his life is a failure until his guardian angel (Henry Travers) shows him what life would have been for his family and friends if he hadn't existed. In the end, the townspeople gather to support George in his greatest financial struggle, proving that no man faces the world alone as long as he has friends and love. It's a Wonderful Life, which received five Academy Award nominations (but no awards - The Best Years of Our Lives took them all that year), is Capra's own personal favorite among all his films (he watches it each Christmas). It was remade for television in 1977 as It Happened One Christmas, with Marlo Thomas in the Stewart role.

The Homecoming-A Christmas Story. Before there was The Waltons, there was this 1971 forerunner, a TV movie featuring Patricia Neal, Edgar Bergen, and Richard Thomas in the kind of warm family tale that became a staple on the popular series. The story, based on Earl Himner Jr.'s recollections of his youth (previously the basis for the 1963 Henry Fonda movie Spencer's Mountain). won critical kudos, a Christopher Award, and three Emmy nominations. It also convinced CBS to try a, series, and although The Waltons was a slow starter in tho ratings, it became the most popular show in its tirneperiod for seven years. The Homecoming, rerun almost every year, appeared five times on Variety's "Toprated Movies on TV, 1961-1979" list, a record for a TV movie.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:455:]]Made-for-TV Christmas Movies. The made-for- TV-movies most frequently shown on local and network television include a cross section of good, bad, and indifferent stories, all linked together by the goodwill, importance-of-human-relations theme. A Dreamfor Christmas (1977), written by Earl Hamner Jr., is the saga of a black congregation's struggle to survive in 1950s Los Angeles. A Christmas to Remember (1978) features Jason Robards as an old man, embittered by the death of his son, who learns how to love again by bringing up his grandson. The Gathering (1977), an Emmy winner that spawned a 1979 sequel, The Gathering, Part II, stars Ed Asner as a crusty businessman trying to work out his tangled family relations on the Christmas before he dies. Silent Night, Lonely Night (1969) brings Lloyd Bridges and Shirley Jones together as a lonely couple during a brief Christmas Eve encounter. The Man in the Santa Claus Suit (1978) features Fred Astaire playing seven different roles in a you-can-have-it-if-youwish-for-it collection of stories. Christmas Lilies of the Field, a whimsical 1979 sequel to the 1963 theatrical film, finds Billy Dee Williams helping a group of nuns, while Sunshine Christmas (1977) follows musician Cliff De Young home to his estranged family for the holidays. On the historical side, The Nativity (1978) recreates'the courtship of Mary and Joseph, and the first Christmas; and Christmas Miracle in Caufield, U.S.A. (1977) shows what happened on Christmas Eve 1951 when coal miners were trapped underground' by an explosion.

Amahl and the Night Visitors. On Christmas Eve 1951, NBC broke new ground with an opera, by Gian-Carlo Menotti, specifically written for television, Amahl and the Night Visitors, and the network rebroadcast the story every year until 1966. Well received by critics and viewers, the story concerns a crippled boy's encounter with the Three Wise Men on their way to the Christ child, and the Christmas lesson he learns about giving. In 1978 NBC staged a new version" filmed in London and Israel, which has been rebroadcast on public television every year sInce.

Children's Specials. The best children's specials are usually the older ones. A Charlie Brown Christmas, first broadcast in the 1960s, shows there is more to Christmas than commercialism. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), with Burl Ives singing the hit song, uses stop-motion (animation of three-dimensional figures) to tell how Rudolph saved Christmas. How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1966) is a Dr. Seuss cartoon-poem narrated by the late Boris Karloff, while Frosty the Snowman (1970) depicts the life of a happy snowman. "When things are produced for little children," an ABC executive remarked in TV Guide, "they have a new audience every year. Peanuts specials will run till the sprocket holes wear out."

Christmas Videotapes. If you can't catch a special or TV episode when it is broadcast, you can always record it on videotape or, sometimes, rent or buy it. The above-mentioned movies available on tape include: Scrooge (1970), Miracle on 34th Street (1947), Holiday Inn (1942), It's a Wonderful Life (1946), and Babes in Toyland (The March of the Wooden Soldiers, 1934). Also available are three special Christmas tapes: The Night Before Christmas and Silent Night, Holy Night, both holiday cartoons; and Merry Christmas to You, a compilation of cartoons and Christmas episodes of Lassie and The Lone Ranger from the 1950s. Prices begin at $64 in most stores.

DIVERSION, December 1982

Cinema Spin-offs

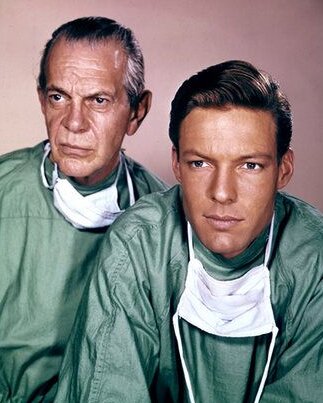

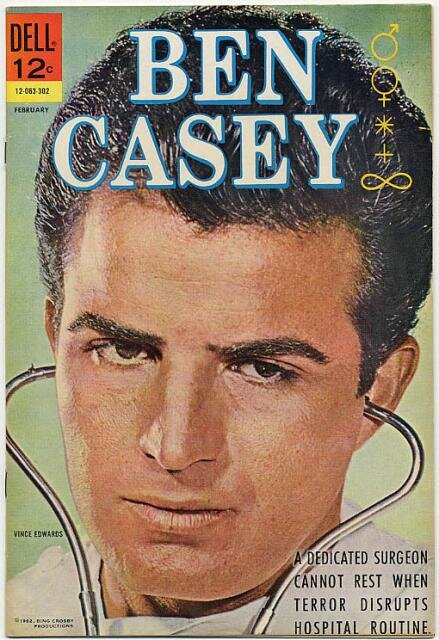

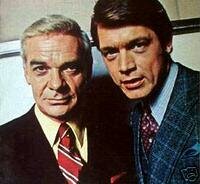

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1408:]]

What do Casablanca, Private Benjamin, Planet of the Apes, Shaft, The Third Man, and The King and I have in common? When these popular movies were transformed into television series, they all failed miserably.

This is the age of endless cinematic sequels-from Rocky III and Star Trek II to James Bond XI. But for years, television has been going the sequel mill one better by reincarnating hit movies as all kinds of small-screen fare.

The list of adaptations ranges from such comedies as M*A*S*H, Going My Way, and The Odd Couple to dramas and adventure series like King's Row, Dr. Kildare, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and Fame. In 1982 new spinoffs from the movies included9 to 5, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers, and The New Odd Couple. And this past spring, yet another TV version of Casablanca came and went as three-week series.

No Knack For Knockoffs

Although few of these stepchildren succeed, the ones that do, such as M*A*S*H and the original Odd Couple, usually inspire the network executives to new heights of imitation. Karl Tiedemann, a former writer on NBC's Late Night With David Letterman, says, "The thinking runs that if a movie is a hit, a TV series with the same elements will also be a hit."

"Hollywood is a town of memory and insecurity," adds Josh Greenfeld, the screenwriter of Harry and Tonto, a successful movie that was considered for a TV pilot. "You get a head start and a pilot deal more easily because producers have a better idea of what they're going to get."

But hit movies rarely make waves in the TV ratings. "There are different requirements on television," notes Stefan Kanfer, senior editor and media watcher at Time magazine. Good characterization can be more crucial in a TV show than in a theatrical film.

"The Odd Couple is basically a one-joke idea," says Tiedemann. "So was Barefoot in the Park [which premiered at the same time]. Barefoot was likable but had thin and superficial characterizations. They were not very interesting. But in the TV version of The Odd Couple, certain aspects of the film characters were well developed. Felix became a person who always wanted to help and who always went one step too far and regretted it. It was great character comedy."

Cashing in on M*A *S*H

Characterization was also the key to the long-running M*A*S*H series, which began life as a novel and then in 1970 became an unexpectedly successful Robert Altman film starring Elliott Gould and Donald Sutherland. When M*A*S*H came to CBS in 1972, it seemed an unlikely vehicle for television: a black comedy about the wild goings-on in an army medical unit during the Korean War.' In fact, it almost' didn't survive its first season.

"What made M*A*S*Hultimately work for television," says Bill McLaughlin, creative director for the cable TV comedy show Videosyncracies, "was that it got away from the wackiness of the movie and eventually settled into a show about relationships. The movie was not all that personal. It was more a situation movie. As the television program grew, so did the characters. We cared about them."

And now M*A*S*H will have an afterlife, in more ways than one. The original series has been syndicated and will therefore live on in rerun heaven. The sequel, AfterMASH, is scheduled to debut sometime this fall.

Another military comedy, Private Benjamin, took a different approach. The movie on which it was based starred Goldie Hawn and followed a young woman's growth in boot camp from spoiled child to responsible adult. As in the M*A *S*H TV series, the central character evolved in the course of the story. In the television version, however, such change was problematic. "We can't resolve the conflict like the movie did," said Benjamin star Lorna Patterson in 1981. "As soon as Judy Benjamin matures as a woman and a human being, the series is over."

But without that character development, there was little to interest viewers. “It was just another wacky sitcom with flat characters," recalls McLaughlin. Not surprisingly, Private Benjamin lasted only about a year and a half.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1407:]]

Not Always a Great Notion

Going beyond the original concept does not always work either, as Michael Rennie found out in his 1959 TV series, The Third Man. Adapted from the 1949 film, which starred Orson Welles as mystery man Harry Lime, the TV show filled in the blanks and turned Lime (played by Rennie) into a suave financial speculator and amateur sleuth. There was little that made the series stand out from other crime shows, and it lacked the atmosphere and suspense of the famous movie. The series died quickly.

Altering the concept can also, paradoxically, strengthen the point of the original story. For example, 9 to 5, based on a Jane Fonda-Lily Tomlin-Dolly Parton movie that broadly caricatured male-chauvinist and feminist attitudes, was softened for television.

"I wanted more warmth," Jane Fonda, one of the producers of the series, told TV Guide. "The boss, for example, was too much of a buffoon, a straw man for the secretaries. We redesigned the role . . . to make him a worthier human opponent for them, less a chauvinist cartoon .... The series 9 to 5 is less pointed than the film, and a heavy-duty feminist series we’re not and never will be. We're not going to do an issue a week-it has to be very subtle or it's boring. And boring shows don't last."

Monkeying with the Movie

When it debuted in 1974, Planet of the Apes seemed likely to succeed on television. Based on a popular film and its sequels-which CBS had recently broadcast to tremendous ratings-the TV series starred Roddy McDowell in a re-creation of his movie role. Nevertheless, it ended up among the lowestrated programs of the season.

"Planet of the Apes didn't have a strong premise," says Time's Kanfer. "In the original movie, there was a good idea for the ending: the ape-ruled planet turned out to be Earth. But once you found that out, all you could do was watch the costumes."

Apparently, the presence of a star from the movie makes little difference to audiences. Shaft, a series based on three black exploitation adventure movies, featured Richard Roundtree in the same title role he had created on the big screen. But the leather-jacketed, foul-mouthed, violent sleuth was sanitized so much for TV that there was hardly any resemblance between that character and his cinematic namesake.

Yul Brynner, another movie star, made the jump to television as the popular Siamese monarch he had played in The King and I, a stage and screen success. The series, Anna and the King, was a flop, despite the actor's

"Brynner performed as regally as he had in the film," says Jim Sirmans, a spokesman for CBS. "The fault was probably not with him." Adds Kanfer, "When a movie star goes into a TV series, the public perceives it as a step down for him, indicating that he can't get film parts anymore. And that can be a mark against the series."

Star-Crossed

But the public's memory of the original star does not always hurt a replacement. "There's a danger, in doing a part originated by someone else," admits Linda Lavin, star of the popular Alice (based on the 1975 movie Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore). "But I was very moved by its personal and human qualities. I like Alice."

"Ellen Burstyn won an Academy Award for Alice' Doesn't Live Here Anymore," says Sirmans. "Yet now everyone thinks of Linda Lavin as Alice. That's what TV will do. Viewers see the performers every single week so there's that constant exposure, which reinforces audience identification. I'm not saying it's good or bad. It’s just the way TV is.”

"A successful adaptation depends on whose hands you have working on it," he continues. “It always begins with the writer, the actor, and the director. Can you imagine M*A*S*H in less talented hands than Larry Gelbart's? Or having a less experienced cast than Alan AIda and the rest?"

Den of Thieves

But television is also a highly imitative medium, and what it doesn't adapt, it often copies outright. "If television executives detect a trend, they will steal," remarks Greenfeld. "Happy Days obviously derives from American Graffiti, Tales of the Gold Monkey from Raiders of the Lost Ark. Why buy the movie for TV when you can imitate it? You know, larceny is the cheapest form of flattery."

In the future, however, the television industry might not have as many opportunities to create new series based on movies. "I don't think M*A *S*H would have gotten on the air today," comments Greenfeld. "The movie companies would have made M*A*S*H II. They feel they're better off turning one'successful movie into another successful movie." And judging from the track record, they may be right.

DIVERSION AUGUST 1983

Comedy on the Rocks

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:728:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:729:]]

My friend Michele is a screwball. She's beautiful, bright and befuddled, and talks in paragraphs, not sentences, with barely a breath between words. You ask her one thing, she answers a dozen-usually going off on tangents you never knew existed. Conversations with her sometimes remind me of one Carole Lombard has with William Powell in 1936's My Man Godfrey: "You're more than a butler. You're the first protege I ever had ... Like Carlo ... He's mother's protege. It's awfully nice Carlo having a sponsor because he doesn't have to work and he gets time for his practicing but then he never does and that makes a difference ... Do you play anything, Godfrey? Oh, I don't mean games or things like that, I mean the piano and things like that. .. Oh, it doesn't really make any difference. I just thought I'd ask. It's funny how some things make you think of other things. "

Other times, I feel like Cary Grant in 1938's Bringing Up Baby, when he tells Katharine Hepburn, "Now, it isn't that I don't like you, Susan, because, after all, in moments of quiet, I'm strangely drawn toward you, but-well, there haven't been any quiet moments."

Yes, Michele would fit right into a screwball comedy.

Screwball films are known for their beautiful, batty women whose fast speech and zany actions conceal a brainy purpose (usually to ensnare a man). They are also known for their outlandish yet strangely down-to-earth plots, their sentimental cynicism and, as critic Otto Ferguson put it, "their frequency of absurd surprises that combine sight, sound, motion and recognition into something like music."

The genre was a product of a particular period. In the mid-1930s through the mid-1940s, crisis and change in American life left people feeling as dizzy (from the Depression and World War) as the onscreen heroes listening to the screwball girls.

The masters of the form included a handful of directors who did nothing else quite as well-Preston Sturges, Frank Capra, Gregory La Cava-and others, like Howard Hawks and W.S. Van Dyke, who moved with ease among comedies, adventures and dramas. The screwball film began inauspiciously enough with Capra's low-budget it Happened One Night (1934) and Hawks' Twentieth Century (1934). The former, a sleeper hit, was a change of pace for Capra, who had been known for action pictures and melodramas like Dirigible (1931) and The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933). No one had much faith in it, either: Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, forced into the movie by their studios, badmouthed it. Hollywood insiders predicted disaster.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:730:]]

Its surprising success, however-Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Actor and Best Actress Os cars-led to a rash of screwballs and a new career for Capra, who went on to shoot such likeminded populist comedies as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), You Can't Take It with You (1938), Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Meet John Doe (1941). The genre blossomed with Van Dyke's The Thin Man (1934), La Cava's My Man Godfrey (1936), Hawks' Bringing Up Baby (1938) and the lunatic body of work by Preston Sturges.

Sturges is the king of the screwball. The European-educated inventor and songwriter began writing Hollywood screenplays in the 1930s (including a supposed forerunner to Citizen Kane called The Power and the Glory, and an excellent comedy with Claudette Colbert, Midnight). But he was unhappy with the interpretations of his scripts and, in 1940, negotiated a then unusual writer-as-director deal. Over the following four years he turned out a string of brilliant, manic hits: The Great McGinty (1940), Christmas in July (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), Sullivan's Travels (1941), The Palm Beach Story (1942), The Miracle of Morgan's Creek (1944) and Hail the Conquering Hero (1944). But the enfant terrible was a briefly burning light; he seemed to run out of gas after that. "Sturges is a fascinating director," wrote critic David Thomson, "deeply rooted in a merry, corrupt but absurd America, as wayward and frequently misled as an inventor but, at his best, the organizer of a convincingly cheerful comedy of the ridiculous that is rare in American cinema."

THE FORMULA

Although each individual director perfected and expanded the form in some way, screwball comedies-as established by Hawks, Capra, et al.-invariably follow a formula. Usually there's a heroine who's either smarter than the guy, daffier than the guy or colder than the guy. In the course of the movie, she will sequentially despise him (but still get entangled in his affairs), come to admire him (even as she fights with him) and finally realize she loves him. In the process, she will also change from spoiled or cold or daffy to concerned or warm or slightly less daffy.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:731:]]

Then there's the guy. He's either cynically sentimental, using a wisecrack to cover his feelings (Claudette Colbert to Clark Gable in It Happened One Night: "Your ego is absolutely colossal." Gable: "Yeah, not bad. How's yours?"), or else hopelessly repressed and befuddled. In the first instance, the heroine brings out the romantic in the hero, as he comes to realize that there's more to her than he thought. In the second case, the hero realizes there is. more to life than being straitlaced, as Roland Young does in Topper (1937), the story of a spiritually "dead" banker who is brought to life by two carefree ghosts (Cary Grant and Constance Bennett): "I want to dance! I want to drink! I want to sing! I want to have fun!"

That's the other classic key ingredient: the almost childlike nature of the heroine, who constantly defies convention and thereby helps unstuff the hero's shirt. There's a child inside all of us, say the best realizations of this genre, repressed by the constraints of society. To be slightly crazy is to be imaginatively free. And, notes critic Gerald Weales, "if the craziness is seen as a function of wealth in the 1930s, it is because irresponsibility in that decade was most easily identified in terms of the cushion that money put under it."

Besides the girl, the guy and the crazy antics, there are the Pursuit and the Misunderstanding. In The Awful Truth (1937), husband Cary Grant suspects wife Irene Dunne of philandering. They have a childish fight which ends in divorce-even though everyone knows they really love each other. (The battle is another element of the screwball, for as Hepburn puts it in Bringing Up Baby: "The love impulse in a man frequently reveals itself in terms of conflict. ") The movie is the tale of their pursuit of each other, as each tries to break up the other's intended remarriage to someone else.

On the way, there is slapstick (another typical screwball device), fast dialogue and much cynicism. Says Grant with tongue in cheek, "There can't be any doubts in marriage. Marriage is based on faith. And if you've lost that, you've lost everything." Yet underneath lies the rich vein of sentimentality which once prompted Sturges to remark, "Fish and guests stink after three days, they say, but your wife isn't a guest but definitely a part of you-your other half for better or for worse ... and you die without her."

On the surface, the screwballs project a dark world where, as a character in Sturges' The Miracle of Morgan's Creek (1944) notes, "everyone suspects the worst of everyone else." In that film, for instance, misunderstandings pile on top of each other so fast and so brilliantly that you're left breathless. It's the story of Trudy Kockenlocker, a small-town gal who gets herself into a pile of trouble when she goes out dancing with soldiers against her father's orders. She ends up married and pregnant but doesn't know who the father is. The movie deals hilariously with her attempts to untangle the mess and her discovery that she loves the hero, a schnook named Orville Jones.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:732:]]

There are many witty moments, among them Constable Kockenlocker's speech about daughters. "They're a mess no matter how you look at 'em, a headache till they get married-if they get married-and, after that, they get worse ... Either they leave their husbands and come back with four children and move into your guest room or their husband loses his job and the whole caboodle comes back. Or else th~y're so homely you can't get rid of them at all and they hang around the house like Spanish moss and shame you into an early grave."

Kockenlocker, a far cry from Frank Capra's patented sentimental dads, is another screwball staple: the eccentric secondary figures, who are often funnier than the leads. The trend began in It Happened One Night, when Gable and Colbert are picked up by a farmer who likes to sing. When he learns they're not hungry, he improvises a song called "Young People in Love Are Very Seldom Hunnn-gry."