Essays on Life

Greece

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:89:]]

THE RUINS OF VASSAE

The small car came bumping down the narrow cobblestone road. Suddenly it stopped, confronted by an imposing gray taxi advancing in its path. The irate cabbie's horn sounded savagely and he unleashed a series of oaths. Three more cabs lined up behind him and the passengers of the offending car tumbled out, laughing and chatting nervously in French. I watched in silence as the driver of their car, accompanied by a chorus of horns, backed up his small vehicle to a point narrow enough for the other cars to pass. They'did so, in great relief and evident disgust; they were in a hurry and had no time for misguided tourists.

The scene was not a street in New York during rush hour, but actually one in Plaka, the small, island-like section of Athens that is located under Greece's most famous site, the Acropolis. The traffic jam seemed incongruous in that classical setting; but the mixture is sadly not an uncommon one in Greece today.

"Progress" is slowly intruding on the land of Homer, and it is not unusual to see an old taverna existing side by side with the Grecian equivalent of an A & P. In Athens on a recent trip, such changes were very noticeable. Coca-Cola billboards littered the surrounding countryside. Down one street, a dough-brick house, which might have been a century old, was marred by a large sign over the 20th century storefront imposed on its main floor; "Union Chloride," said the English letters under the 17th century Venetian archway. And elsewhere, "Coke! It's the real thing." New skyscrapers, once a rare sight because of strict zoning ordinances, are now going up every day. And since the destruction of churches is forbidden in Greece, one such skyscraper has a small, decades-old church located in its lobby. Like the Venetian building with the Chloride sign and the blaring horns under the Acropolis, it, too, is a curious reminder of what was, amidst what will be. There is also talk of replacing the Parthenon's columns with plaster substitutes; the ever-increasing pollution is destroying the spiritual past as slowly and subtlely as Coke and high rises are destroying the physical one.

It's a sobering feeling that almost disappears as you drive through the Peloponnesus, the southern peninsula of Greece. There, you can find many small villages that recall another time when warmth, friendliness and simplicity were pervasive. Not, much happens, or, at least, not much that we'd think about. Mr. Kouriklas worries about his chickens and Mrs. Nikolopolous frets about her goats; Madame Taki wonders when it will rain, and Papou Nikos tells stories to his nephew's son. To them, strangers are a novelty, to be treated hospitably. In Marathea, my mother's village, many of the villagers remembered when I had been there last, as a small boy, 15 years before. They were pleased that I had come back.

Tom (left) and family in Mani, 1962.

Tom (left) and family in Mani, 1962.

These people, in their small hamlets, are mostly old men and women caring for their grandchildren. The youth have left for Athens; they have forsaken the two-story castle-like homes that their great-great grandfathers built for them. Many of these structures have collapsed from neglect; others are inhabited by pigs and goats. For the young, excitement is in the city. And that city is now enroaching here as well. Television antennas and telephone poles dot the landscape almost as frequently as do the tall, thin cyprus trees that one writer compared to "exclamation points in a laconic landscape."

The Peloponnesus is laconic, but it is also striking for its contrasts and beauty. Lush mountains often give way to arid, rocky, uninhabitable land; smooth, sandy beaches alternate with rough, rocky ones; and blue skies fade into romantic mists. Here, it is not hard to see where Homer and even Haliburton received their inspiration. And the people. The villagers – especially the old men – are as striking as the countryside: they have a proud, rough beauty that is poised against gentle – almost humble – manners. They are in no hurry and are nothing if they are not kind. Lost on the road, I stopped and asked an old man on a donkey which way to go. His reply was apologetic, a bit angry at himself not me: "You made the wrong turn up there," he said, indicating the hilltop. "I saw you doing it. If only I had been there, I would have told you." Foolishly, touchingly, he felt responsible. This kindlness is a common trait here and contrasts noticeably with the unconcern and impatience of the residents in New York or Athens. The pace here is easy and friendly and the people can afford to look at themselves humorously, unruffled by the growing trickle of tourists that signals the beginning of the end to their their way of life. I thought of that later, when lost again, I asked a group of old villagers where the ruins of Vassae were. "We are they," was their straightfaced reply. And so they were, in a way more real than any temple could ever be. from COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR, 1978; slightly revised in 2009

A LOOK BACK This was the first published personal essay I wrote, a form I would not try my hand at again for over three decades. I remember at the time – I was only 21 – I was very nervous about the piece and I showed it to my father for his input. He was pleased with the article and made a number of useful suggestions, the only one that I remember being his saying I should insert the word "even" before the reference to Haliburton. Richard Haliburton was a long-forgotten writer of my father's youth (he had written a memoir of Greece called The Glorious Adventure), and my father thought that my original alliterative phrase, "Homer and Halliburton" was assuming the reader knew more than he probably did. I've made some minor stylistic edits, but the story is more or less as it first appeared (although I always hated the title my editor gave it, "Greece: The City Approacheth," as though the "city" were some comic book monster out of a bad Marvel comic).

A LOOK BACK This was the first published personal essay I wrote, a form I would not try my hand at again for over three decades. I remember at the time – I was only 21 – I was very nervous about the piece and I showed it to my father for his input. He was pleased with the article and made a number of useful suggestions, the only one that I remember being his saying I should insert the word "even" before the reference to Haliburton. Richard Haliburton was a long-forgotten writer of my father's youth (he had written a memoir of Greece called The Glorious Adventure), and my father thought that my original alliterative phrase, "Homer and Halliburton" was assuming the reader knew more than he probably did. I've made some minor stylistic edits, but the story is more or less as it first appeared (although I always hated the title my editor gave it, "Greece: The City Approacheth," as though the "city" were some comic book monster out of a bad Marvel comic).

Goodbye to All That

Sunday, March 9, 2003

So we finally split up today. To call it bizarre is an understatement -- but, then, the whole relationship was bizarre. The way she clung to her parents, was obsessed with their lives and they with hers. It gives me the creeps.

She made pancakes. It was so like her. Everything was neatly arranged: the plates, the silverware, the perfectly cut fruit, the phony flowers sitting in a waterless vase. Just once I’d like to see her embrace the chaos and disorder of life, instead of fleeing from it. So scared. I felt sorry for her -- and myself for clinging to her so hopefully for 11 sexless, middle-aged months. “Only people over 60 have artifcial flowers,” said CF later; I remembered what W's cousin had said to me on the train, “She never rebelled. She never fought her parents. At least I don’t remember it. She was always an adult.”

I sat there, eating the pancakes with the tasteless, sugar-free, low-fat syrup, and listened as she prattled on about God knows what. It was like we were two old drinking companions (except she never drinks), not two would-be, never-were lovers who, after 11 months of holding hands and one big argument, were now facing the end of the road.

Even my recent illness was treated as tea time chatter: polite concern with a sequeway to how great Robin Williams had been in AWAKENINGS. Why was I here? Would I have to do the breaking up?

Then, finally, like a quick summer shower, it was over. She escorted me into her living room, talked about where the chandelier would be hung, how the mirror would add depth to the room, and how I should search for someone who could say “I love you” to me. But she wasn’t the one. My talk of her family

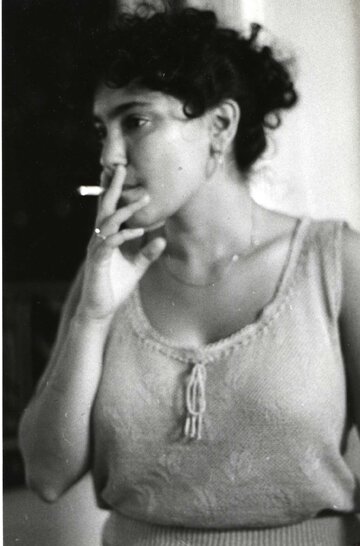

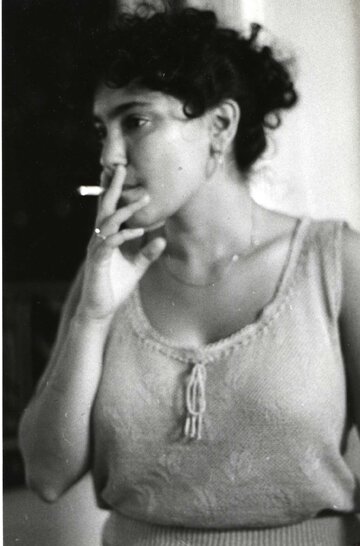

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:16:]]

on Monday and of the need to have a real relationship, had made her “physically nauseous.” Not a word about what I had meant to her. Because I meant about as much to her as the pretty stuffed pillow I was sitting on. Maybe less.

I said goodbye -- after saying two things: that she couldn’t have a relationship with a man until she stopped having a love affair with her parents and that if she couldn’t say, “I love you” after 11 months, she never would.

We embraced, promised to keep in touch (I knew it was a lie), and as I walked out I thought two things simultaneously: I wished I had exited the relationship sooner – and the pancakes weren't half-bad.

Abandoned Love

NO COOKIES FOR GERARD

NO COOKIES FOR GERARD

"Do you want a cookie?" I said to the wide-eyed twentysomething young woman who looked back at me.

And with those five words began my frustrating, bittersweet one-sided love affair that never should have been with Carol. She was actually just six months past her 21st birthday; I was all of 20 and, like most 20-year-olds, felt I had just met "her," the woman of my dreams, the woman I was going to marry, the woman I would always love.

I had seen her around the campus, her compact yet buxom figure walking with determined strides to classes, to coffee, to wherever. She always flashed me a big, welcoming smile, encouraging me to think that she wanted to meet me, to talk with me, to be part of my life. I'd seen her everywhere, till soon, she was like the posse in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, pursuing me endlessly, in my dreams if not my waking life, as I wondered, "Who is that girl?"

But I eventually became the pursuer not the pursued, chasing her over the next decade, like some real-life Lieutenant Gerard, always thinking that, "This time, I'll get her, this time she'll be mine." It was a harmless obsession, I told myself. But did Ahab ever get much good from that whale?

Our meeting came about through a mistake. She tossed me that smile one day on campus, and I was determined to know who this will-of-the-wisp was. I ran after her, introducing myself. She told me her name and that she was an anthropology student here from Chicago. I walked with her, we talked; she laughed; I laughed. It was bliss.

Four days later, I saw her again at the library. She gave me that big Colgate smile, her round brown eyes as alluring as the flame to a fledgling pyromaniac. Encouraged, I offered her a homemade cookie my mother had given me.

"Do you want a cookie?" I said, not realizing that those were the first words I would say to her – for she was not the she I had met just days before but her twin sister ("They look alike, they sound alike, you can lose your mind when cousins are two of a kind"). It was a charming mistake; I was Fred and she was Ginger, and our romance, in my eyes, had just begun.

Alas, it was never to be. I chased her through boyfriend after boyfriend – the sarcastic one who played tennis with her and dined well on her father's credit cards; the emotionally abusive one whom I suspected hit her occasionally; the smarmy intellectual one who was oh-so-superior to everyone and eventually faced sexual harassment charges at work.

Alas, it was never to be. I chased her through boyfriend after boyfriend – the sarcastic one who played tennis with her and dined well on her father's credit cards; the emotionally abusive one whom I suspected hit her occasionally; the smarmy intellectual one who was oh-so-superior to everyone and eventually faced sexual harassment charges at work.

Through it all, I was the "good friend," the Watson to her Holmes, "the one fixed point in a changing age," who would console her, comfort her, but never "date" her. The man who knew too much but was never good enough. We'd go out to dinner, I'd make her laugh, and she'd make me cry with a longing that was never to be fulfilled.

I once even called her my "foul-weather friend." It was my joke because she'd always be ready to advise me, psychoanalyze me, and sympathize with me when I had a problem with a girlfriend, or with my family, or with my life.

"You're so punishing to yourself," she said to me once. Not as punishing as she was to me.

Oh, how you broke my heart. "I'll never marry a non-Jew," she had said at 21 to me, the non-Jew. So definite, so sure of herself. And, of course, a decade or so later, she married a non-Jew, an agreeable fellow who never registered on my radar as anything beyond being a nice, sweet guy. She pleaded with me to go to the wedding, and like some sucker who lost a bet, I turned up, smiling, and danced with her for the first and only time.

It ended, as these things do, mundanely and unromantically. We had kept in touch over the years, but it was always me who did the work, calling her, setting up the meetings, insisting that we meet. She had another life now, apart from me, with two darling children. When we actually met, it was always the same connection, though my passion had long since cooled and hers –well, how can you cool something that was never hot?

I finally got tired of calling her, after she had canceled yet-another scheduled meeting. "You call me when you want to meet," I had said with frustration. Six months later, I still hadn't heard from her.

So, goodbye to all that. To the love, to the pursuit, to the fiction that she really ever gave a damn.

Yet to be human is to hope, and I still have that picture in my head, of the time she went away to Paris to get over another failed relationship. Of when she came back, and I was there waiting for her at Newark airport. She ran to me, embraced me, and kissed me, oh so tenderly. "I hoped you would be here," she had said so happily, so completely. "I knew you'd be here." Somewhere, in some other life, perhaps, we'll meet again, and this time, she'll take the cookie and see that I was the best man after all.

July 14, 2008

Memories of My Mother

NOT ME, KID

By TOM SOTER

“I miss mom. Don’t you?” said my younger brother, Peter, one day soon after Christmas.

"I think about her a lot.”

“I try not to think about her at all,” I lied. I wanted to change the subject. “What’s the point?”

In fact, I was unconsciously repeating one of my mother’s favorite phrases: “What’s the point?” she would often say, though not in any existential fashion. She would say it as she would say any other number of peculiar catchphrases that were so uniquely hers: “Not me, kid,” “He looks dead,” “That’s stupid,” “I haven’t seen you in 10,000 years” (which she might say to a friend she hadn’t seen in a while, not caring how old that would make them both), and my father the grammarian’s particular bete noir: “She’s a prick.”

“You can’t say, ‘She’s a prick,’ Effie,” he would say to her.

“Why not?”

“Because a she can’t be a prick. A prick is male.”

“Well, she’s still a prick,” she would say, grammar be damned.

My father, George, who married my mother on Valentine’s Day, 1949, was continually exasperated by my mother’s stubbornness. When we were growing up in New York City, a blind man and his wife happened to live in our building. My mother would constantly refer to him as “the blind guy,” which bothered my father, probably because it defined the man by his ailment. “Don’t call him the blind guy,” my father would say. “He’s got a name. It’s John.” “Who’s John?” “The blind guy!” said my father, falling into her trap. “There, you see,” she said, triumphantly.

My mother hated pomposity and never let my father, a brilliant wordsmith and award-winning advertising copywriter, get too full of himself (the family jokingly referred to him as “The Puppet King”). Effie (her full name, Efftihia, means “happiness” in Greek) had herself come from humble beginnings. She was born in Greece in 1921, the first child of Thomas and Mary Hartocollis, but she spent the first five years of her life with her grandparents in the countryside outside of Athens. That was because her parents had gone to Brooklyn, New York, where Thomas managed real estate and Mary managed him. If Effie felt abandoned, she never said so directly, though she hinted at her feelings when she would retell the story of her youthful years with her maternal grandparents, and how her mother was shocked, on returning from America, to discover that Effie had adopted her grandparent’s surname in place of her own. “I had forgotten my parents,” she would explain.

My mother came to America in 1939, where her three siblings had all been born. “In the early ’30s,” George recalled in 2008, “her father had deposited his wife and four children in Greece (to preserve their Greekness of language and morals) while he worked away in Brooklyn, sending checks and showing up for short periodic visits at their outpost in Athens.”

Effie and George Soter, with firstborn, c. 1955.

Effie and George Soter, with firstborn, c. 1955.

It was while attending Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, that she met my father, a Chicago-born Greek-American attending classes at the college as part of his army training. As he said to me years later, “I had heard there was a Greek girl at Clark, so I went up to her at a college dance and asked her to dance. She thought I was interested in her because her uncle [with whom she was living] owned a restaurant and was ‘wealthy,’ so she tuned me down. Again and again. And the cooler she got, the more interested I became.”

My mother’s resistance apparently didn’t last long. Soon after that, they were dating, for as my father said in a 2008 memoir: “To the Greek-American me (almost all Greek-Americans had village roots), a ‘girl from Athens’ had a bit of the aura that ‘a girl from Paris’ held for almost anyone else: sophisticated, worldly, soigné, wow! When I was shipped off to my relatively un-bellicose tour in Europe, our romance continued by mail.” Although they rarely talked about it, their’s seemed to have been a romantic, passionate love. Once, my mother showed me a shoebox full of letters from my father during the war. I looked at one: it was covered with handwriting on both sides, but the writing was only three words, a phrase repeated dozens of times: “I love you.”

I often think of that shoebox full of letters when I think of my mother. She was so fond of her memories, of recalling the happy moments from her past. She was a collector of keepsakes, her desk a rat’s nest of odds and ends – a program from a show I had been in, a grade-school notebook from my older brother now in San Francisco, a bookmark from my younger brother’s bookstore. But her greatest memory trove was the collection of photo albums. My mother would spend hours assembling photos of trips, dinner parties, birthdays, and other special events into albums. “Have you seen the latest album?” she would say with pride, and then present it: photos under plastic sheets, with captions and commentary by Effie.

She was an obsessive chronicler of memories. I always knew that, but it came home to me when I was recently helping my father clean up his apartment. In the process, we came across a thick, stiff-backed stenographer’s pad, with my mother’s distinct handwriting on the cover: “From 9.28.89 to 9.08.99.” I flipped open the book and saw two columns of writing. The first entry said: “9.28.89 (Audi) Beets. Salad. Cranberry Pie.” The next entry was “10.1.89 Chris’s birthday. Egg lemon soup. Leg of Lamb. Potatoes. Broccoli. Corn. Salad. Cake. Baklava.” The next: “10.12.89. Poker. Addie, John. Fish Soup. Guinea Hens. Broccoli. Rice. Salad. Apple Pie.” And on and on, an almost daily log, for pages and pages of what she had served and to whom she had served it – an amazing book of its kind, a memory book of memories no one should care about, so typical of its writer, so sad in retrospect.

Effie and Tom, c. 1957.

Sad because my mother, though she is still alive, is barely recognizable as the feisty woman who would say things like, “If I were you, I’d jump out the window” and “That’s stupid.” In the early ‘90s, she developed Alzheimer’s and the illness slowly and mercilessly erased the personality she had spent so many years perfecting. A scholarship student, a former social worker, a shopkeeper, a talented needlepoint “artist” (she made dozens of pillows out of old fabric, which she would give to family and friends), a wonderful cook, a great storyteller, a constant reader of fiction and non-fiction alike (her harshest charge against someone once was, “He doesn’t read, can you believe it?”), and a devoted mother and wife – all of that was eventually taken from her, as she became a ghost of herself. It took a long time – I always believed it was my mother’s stubborn willfulness that kept her cognizant for so long – and the last thing to go was her card playing.

My mother loved to play cards. It was ingrained in her from youth. She often told the story from her early teenage years, when her mother needed a fourth person to fill out a card game.

“Come down and play, Effie,” Mary called to her daughter.

“I can’t, mother. I’m studying.”

“You can study anytime. Come play cards, now.”

It was always a good time to play cards in Effie’s world – and she clung onto it for such a long time that even her doctors were amazed. When she couldn’t read or write anymore, and her cooking skills were gone, she could still whip you at cards. My poor father often would sit for hours on end, condemned to non-stop games of Onze, a kind of gin rummy game, until he would finally say “enough,” or be relieved at his post by a family member or friend.

But even that, too, finally was taken away. Her powerful will was broken, her ability to continue the battle, gone. The memories, so precious to her, were now only preserved in books or in the memories of others. When I see her these days, stooped and vacant, being led around by a nurse, I often want to cry or cry out, “Where did you go, mom? Why did you go like that?”

But then I’ll take her hand and lead her around the room myself. And she’ll smile a vacant but pleasant smile, and somewhere inside her I have to believe that a part of her still knows me, or at least knows my feelings. And sometimes, all too rarely, there is a glimmer of acknowledgment if not recognition. “You’re a nice boy,” she will say, suddenly. “I like you.”

I miss you, mom.

September 2008

Memories of My Mother (2)

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:468:]]BIG DEAL

My mother died today. But she had actually left us a long time ago, her identity erased by Alzheimer's Disease – bit by bit, drip by drip, in a painful process that would be heart-wrenching in any situation but was especially poignant with my mother. For my mother, Effie, treasured her memories: to her, the past was not something to be discarded like an old shoe but something to revisit again and again like an old friend.

Indeed, one of the activities that she enjoyed was making photo albums of people, places, and events. She had dozens of albums – at least 80 or 90 by my rough count – ranging from 11 x 14-inch mega-albums down to 4 x 6-inch mini-albums. They were invariably labeled on their spine in my mother’s distinctive handwriting with such practical titles as “Family A-H,” “Tom’s Graduation,” and, my particular favorite, “Friends and the Lemon” (which would often be referred to as “Friends of the Lemon”). There were two 4 x 6 volumes of the Lemon series, which was a bizarre collection that only my mother could concoct of people posing with the lemon tree that she was growing by her desk. “Would you like to see our lemon tree?” she would ask guests. People were amused and would pose awkwardly with the tree, and Effie got a kick out of their reaction.

My mother had a puckish sense of humor. During the 1976 presidential campaign, our family – life-long Democrats – accidentally received campaign literature from the Republican in the race, Gerald Ford. The packet included some phony snapshots of Ford with his dog and his family, with faux handwriting on the back saying, “This is a favorite shot of me and my dog” and “This is a favorite shot of my family.” Effie took the snapshots and placed them in her “Friends” album under the letter “F” for “Ford.”

Effie had catchphrases that she would use constantly, and anyone who knew her will remember her favorite sayings: “I haven’t seen you in 10,000 years,” “Not me, kid,” “That’s stupid,” “Who’s bright idea was this?” “Big deal,” “Who cares?” and my father the grammarian’s particular bete noir: “She’s a prick.”

“You can’t say, ‘She’s a prick,’ Effie,” he would say to her.

“Why not?”

“Because a she can’t be a prick. A prick is male.”

“Well, she’s still a prick,” she would say, grammar be damned.

My father, George, who married my mother on Valentine’s Day, 1949, was continually exasperated by my mother’s stubbornness. When we were growing up in New York City, a blind man and his wife happened to live in our building. My mother would constantly refer to him as “the blind guy,” which bothered my father, probably because it defined the man by his ailment.

“Don’t call him the blind guy,” my father would say. “He’s got a name. It’s John.”

“Who’s John?”

“The blind guy!” said my father, falling into her trap.

“There, you see,” she said, triumphantly.[[wysiwyg_imageupload:478:]]

My mother hated pomposity and never let my father, a brilliant wordsmith and award-winning advertising copywriter, get too full of himself (the family jokingly referred to him as “The Puppet King”). Effie (her full name, Efftihia, means “happiness” in Greek) had herself come from humble beginnings. She was born in Greece in 1921, the first child of Thomas and Mary Hartocollis, but she spent the first five years of her life with her grandparents in the countryside outside of Athens. That was because her parents had gone to Brooklyn, New York, where Thomas managed real estate and Mary managed him. If Effie felt abandoned, she never said so directly, though she hinted at her feelings when she would retell the story of her youthful years with her maternal grandparents, and how her mother was shocked, on returning from America, to discover that Effie had adopted her grandparent’s surname in place of her own. “I had forgotten my parents,” she would explain.

My mother came to America in 1939, where her three siblings had all been born. “In the early ’30s,” George recalled in 2008, “her father had deposited his wife and four children in Greece (to preserve their Greekness of language and morals) while he worked away in Brooklyn, sending checks and showing up for short periodic visits at their outpost in Athens.”

It was while attending Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, that she met my father, a Chicago-born Greek-American attending classes at the college as part of his army training. As he said to me years later, “I had heard there was a Greek girl at Clark, so I went up to her at a college dance and asked her to dance. She thought I was interested in her because her uncle [with whom she was living] owned a restaurant and was ‘wealthy,’ so she tuned me down. Again and again. And the cooler she got, the more interested I became.”

My mother’s resistance apparently didn’t last long. Soon after that, they were dating, for as my father said in a 2008 memoir: “To the Greek-American me (almost all Greek-Americans had village roots), a ‘girl from Athens’ had a bit of the aura that ‘a girl from Paris’ held for almost anyone else: sophisticated, worldly, soigné, wow! When I was shipped off to my relatively un-bellicose tour in Europe, our romance continued by mail.” Although they rarely talked about it, their’s seemed to have been a romantic, passionate love. Once, my mother showed me a shoebox full of letters from my father during the war. I looked at one: it was covered with handwriting on both sides, but the writing was only three words, a phrase repeated dozens of times: “I love you.”

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:472:]]They had an old-fashioned love, one that really lasted through good times and bad. For my father, gregarious and outgoing in his nature, was probably not the easiest man to live with. Flamboyant and larger than life, he seemed to dominate every situation he was in and my mother – though she never complained about it – probably had some regrets about giving up her career as a social worker. She was, in fact, quite proud of her advanced degree in social work (her colleague, Carol Gardiner, once told me that Effie was very effective in her job), but family came first, and she had three boys to raise.

I remember that childhood with fondness: though not known as a touchy-feely person, my mother would often say, “I love you,” to us and often say to me (or Nick or Peter), “You’re one of my favorites” – never mind that you could only have one favorite.

We learned English from my mom, too (she refused to teach us Greek because of an incident she repeatedly told about her cousin, Jimmy, running away from school in Worcester, Mass., because his classmates made fun of the fact that he could only speak Greek). Although she lived in this country since she was 17, she always spoke with a distinctive accent – something that we never noticed growing up. The point came home to me (and Peter) when we were corrected (at different times) by our school teachers over the pronunciation of the word, “didn’t.”

“The word is ‘didn’t,” they would say.

“That’s what I said,” would be the reply. “Dint.”

“No, not ‘dint.’ ‘Didn’t.’”

“Dint.”

“No, didn’t.”

We would go back to our mother and report the complaint and she would listen sympathetically, saying, “That’s stupid. Dint they listen to you?”

My mother spent her happiest years raising her family, but was almost as happy when she started working at the family store, Greek Island, a popular boutique of clothing, jewelry, and all things Greek that operated for most of its life (1963-1986) at 215 East 49th Street, in front of the historic Amster Yard. Effie loved socializing, and hob-knobbed with a number of celebrity customers, from Paul Newman (“his eyes are so blue”) to Katherine Hepburn. When Jacqueline Kennedy Onnasis, a famous Grecophile, came into the store in 1968, five years after the shop had opened, Effie was gracious but direct in her opening comment. “What kept you?” she said to Jackie O.[[wysiwyg_imageupload:473:]]

“The shop,” as she called it, soon came to dominate her life. She loved riding the subways to work (“They’re fast. They get you there 1-2-3”) and loved making special orders for customers (I often remember her working until 3 or 4 in the morning, altering a dress or more typically creating something new with imported fabric. She would show me the dress she had created with great pride, to which she would always add a label, “Made in Greece.”)

She was also fiercely protective of the store. When there were a number of after-hours break-ins at the shop, my mother got mad. She came up with a crazy plan to solve the problem: she went down to the store and sat in the dark by the front door with a baseball bat and a camera. As she matter-of-factly explained it: “When someone breaks in, I will take his picture with the camera and then hit him over the head with a baseball bat.” We couldn’t dissuade her from her mission – but my father and brother stood watch across the street to be sure nothing happened. Nothing did.

It was after the closing of the shop that my mother’s life began its downward spiral. She loved the activity of the store, loved to be around family, loved to be busy. But after 1986, the shop was no more, her boys had moved away (Nick to San Francisco, Peter and me to our own apartments in New York), and my father was at the office. She began drinking more, and perhaps it was then that the Alzheimer’s first started to break down this remarkable woman. She began forgetting things – first minor memories and then major ones. She denied there was a problem, however, and fought it with all the weapons at her command. When Peter took her in for a memory test, he reported this exchange between her and the doctor:

Doctor: “What year were you born?”

Effie: “1921.”

Doctor: “What year is this?”

Effie: “1991.”[[wysiwyg_imageupload:476:]]

Doctor: “So how old does that make you?”

Effie: “You figure it out.”

But the illness gave no quarter and slowly and mercilessly erased the personality she had spent so many years perfecting. The scholarship student, insightful social worker, hard-working shopkeeper, talented needlepoint “artist” (she made dozens of pillows out of old fabric, which she would give to family and friends), wonderful cook, great storyteller, constant reader of fiction and non-fiction alike (her harshest charge against someone once was, “He doesn’t read, can you believe it?”), and devoted mother and wife – all of that was eventually taken from her, as she became a ghost of herself. It took a long time – I always believed it was my mother’s stubborn willfulness that kept her cognizant for so long – and the last thing to go was her card playing.

My mother loved to play cards. It was ingrained in her from youth. She often told the story from her early teenage years, when her mother needed a fourth person to fill out a card game. “Come down and play, Effie,” Mary called to her daughter.

“I can’t, mother. I’m studying.”

“You can study anytime. Come play cards, now.”

It was always a good time to play cards in Effie’s world – and she clung onto it for such a long time that even her doctors were amazed. When she couldn’t read or write anymore, and her cooking skills were gone, she could still whip you at cards. My poor father often would sit for hours on end, condemned to non-stop games of Onze, a kind of gin rummy game, until he would finally say “enough,” or be relieved at his post by a family member or friend.

But even that, too, finally was taken away. Her powerful will was broken, her ability to continue the battle, gone. The memories, so precious to her, were now only preserved in books or in the memories of others. I remember visiting her in that friendly yet ghastly nursing home where she spent the last years of her life after my father died in 2009. The place was populated with a Fellini-esque gallery of old men and women, in various stages of pitiful dementia. There was the little birdlike woman who would come up to me conspiratorially and say, “Help me please, darling, help me.” Or the bald man with one side of his mouth turned down in a perpetual frown, who would talk to me like an old friend, but always repeating the same phrase, “Hiya, Mac, can I get a quarter for a cup of coffee?”

Although it was hard for me to take, the nurses seemed to handle them all with great care and affection. They were particularly fond of Effie, who was feisty almost to the end. When she didn’t like something she would stick out her tongue (or even spit out the offending food), speaking in a mixture of Greek, English, and gibberish. It didn’t phase the staff, but they were curious. At one point, a nurse asked me if the word “Scata” meant anything.

“Yes,” I replied, curious. “Why do you ask?”[[wysiwyg_imageupload:477:]]

“Your mother was using it the other day when we were feeding her. We thought it was a word of approval.”

“Oh,” I said, amused. “It's the Greek word for shit.”

As the months went by, my mother’s lucid moments became less and less. There were times when she would surprise you by looking at you intently, as though trying to place you in the jumbled world of her mind, and then would say, quite clearly, “You’re a good boy,” followed by, “I love you.” And, invariably, you would quickly reach out to her, asking for something she could no longer give – an observation, a thought, even one of those distinctive, ridiculous phrases that so defined her personality.

But she never said them again. Toothless (she refused to wear her dentures) and stooped, she spent much of her time wandering the halls of the nursing home, grabbing at the walls, endlessly searching for something she had lost – a memory, a moment, or, perhaps, a way home.

In the end, I think she found it. For, as I sat by her bedside for the last time, Effie still seemed to have a very strong presence, but now she was finally at peace. And then I thought of the albums, the meals, the laughter, and the tears. Of George and Effie, always together, even when they were apart. "Is George coming?" Effie used to say when I would visit her in the middle stages of her Alzheimer's. To each, the other was the most important. My father died in January 2009 -- but only after he had successfully seen that Effie was placed in a top-notch nursing home. And when my father was laid up in the hospital once, I brought my mother to visit him. "It should have been me in there, not George," was her comment when we left.

After she had died, I thought of the last time I saw her alive, tapping on the arm of her wheelchair, seemingly impatient to move on. The doctors later told us that, in the end, she passed quickly. Within minutes of a call from the nursing home warning of her imminent death, she was gone, almost as though she knew it was time to go.

I talked with Nick and Peter soon after that, and we imagined what Effie would have said about her condition of the last few years if she had been able to talk ("You should shoot me, boys"), and Peter told us that he always liked to imagine that Effie, when sleeping, had entered a happier world, where her family and friends were all recognizable and life was one big card game.

"She's probably sitting down to a card game with George right now," said Peter.

"And," I added, "she's probably sayIng to George, 'I haven't seen you in 10,000 years. Good to see you, fella.'"

I love you, mom.

July 20, 2011

Memories of My Father

NO MORE GEORGE

By Tom Soter

“My father died today.” I said it matter-of-factly and was surprised at how calm I was. Within moments, however, like some sort of delayed action tornado, the full force of those words hit me. “My father died today.” No more quick calls to check out a word or phrase that seemed odd or misused; no more last-minute invitations to have dinner and see a movie; no more jokes; no more twinkle in the eye; no more George.

I remember sitting opposite him, a few months ago, at a diner to which he liked to go after seeing me every week in my improv comedy show. It was a funny little place, and I always wondered why George liked it. The food was generally greasy and not very good, the place was loud and my dad’s hearing was bad, and it seemed so out-of-character for a man of such style, a man who loved and appreciated good food.

But he loved life more. Life to him was more than breathing or existing – it was about the people, about the vitality of the situation, about friendship. To be in a place like this was to be in the center of life, to be in a place “where everybody knows your name.” They didn’t know his name at that little coffee shop, but they certainly knew George: they greeted him heartily when he came in every week, he bantered with the waiters and flirted with the waitresses, and they always had his scotch ready for him. Ah, George and his scotch.

Everyone who met George found it hard to forget him. The outpouring of love and shock from those who hardly knew him both touched and overwhelmed me. Noel Katz, one of my piano players at Sunday Night Improv whom I always felt was aloof towards my dad, surprised and moved me with an anecdotal note revealing he had ridden the bus with George on many occasions and spent that time talking to him, “I don't think you're aware how much I learned from him, how much I enjoyed him, how much I'll miss him,” he wrote. Others talked about his ready smile, the twinkle in his eye, the joie-de-vivre that was so much a part of him. “Though I'd had word of George's impending death, it was nevertheless shocking to hear of its arrival,” wrote Stu Hample, a writer and long-time colleague of my father’s. “For George, as everyone whose path he crossed is well aware, gave off the dazzling essence of life in everything he did or said or thought or imagined. In a word, a look, a smile, a flick of his cigarette ashes.”

Carole Bugge, an improviser at my show who had seen George at performances and parties over the last 20 years, even wrote a poem about him, “On Hearing of the Death of George,” which said, in part: “No, that’s not right – death’s not for you…death seems to be for some people - sad, yes, but a natural passing

, but not for you

. You were not young, or well, but some people just aren't the dying kind.”

Indeed, that was a common refrain: how could a man who so loved life leave it behind? He didn’t go willingly, but he did go with style. From the beginning of his illness until the end, he kept his trademark wit. After he was diagnosed with lung cancer, he had news of two other people he knew being stricken with the same disease and quipped, “Everybody’s doing it.” Near the end, he pointed to a sign on the television set in his hospital room that said, “Inquire how you can rent this color television.” He turned to me and – intentionally placing the emphasis on the word color – said: “Why would anyone want a TV set that color?”

Indeed, his wit was part of his ever-present optimism. Although he knew he was going to die, he still talked hopefully of the future. When I visited him in the hospital one day, he was going a little loopy from being confined in bed. But he smiled defiantly and said, “They’re writing my obituary for tomorrow’s paper. Not yet. Not yet.” George in the 1950s.

George in the 1950s.

Although no obituary ever appeared, my father’s life was certainly worth one. The only son of Greek immigrants, he grew up in poverty during the Great Depression, never graduated college, but rose to the top of the advertising world with humor, intelligence, and panache, as one of the original "Mad Men" (a show he hated, saying it only happened that way in a Hollywood screenwriter's mind). He started in the mailroom, and within a few years, was the man behind the "Le Car Hot" campaign for Renault, selling a French car at a time when foreign car sales were a rarity in the U.S. He used an unusually literate approach – until then, car ads were simply functional, bragging about horsepower, steering capabilities, etc. – and was a pioneer in "image advertising."

The award-winning campaign made George's name on Madison Avenue (and was even parodied in Mad magazine as "Der Kar Kraut" and the Yale Record as "Le Magazine Cool"). He went on to create other award-winning (and highly successful) campaigns for Helena Rubenstein, Donald Trump, Air France, the Central Park Conservancy ("You Gotta Have Park" was his invention), and many others.

He was always an optimist. At the height of his success, his boss thought he was getting too full of himself ("I thought I was hot stuff," George ruefully admitted years later), and he was summarily fired. Rather than look for work and confident in his future prospects, George took the opportunity to take the family on a boat trip to his parents' homeland, Greece, a country with which he had a life-long love affair. His confidence paid off; once he arrived (after a 14-day boat trip), he received a call from the U.S. Another agency wanted to hire him.

That kind-of-impetuousness was George’s hallmark. He liked living on the edge, always trusting that the cards would fall his way, and if they didn’t, he’d make the most of what he had. On talking with my cousin Anemona, who housed him in the basement apartment of her brownstone for the last three months of his life, we agreed on one point: George had no problem starting things; he had difficulty ending them. “The only thing he finished was his life,” I said sadly.

But what a life. He was also the co-founder and long-time owner of Greek Island, a fashionable and well-known boutique on East 49th Street, which catered to such celebrities as Katherine Hepburn, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, and Theoni V. Aldredge, among others, and which provided him with reason (if he needed it) to return to Greece time and again. It also provided him with a wealth of stories.

George, 2006For above all else, George was a raconteur, a wonderful teller of tales. For instance, he loved to tell the story of my sick cat, Sally, and how my mother told me one night that animals don’t need to go to the doctor because they get better on their own. Sally died the next day. And – so the story goes – later that year, the Soter family was driving some winding roads in Greece, and I got nauseous. I vomited, and then asked my mother if I should see the doctor. “No, you’ll get better on your own.” My father would always pause at that moment, ready with the punch line: “And Tommy said, ‘That’s just what you said about Sally.’”

George, 2006For above all else, George was a raconteur, a wonderful teller of tales. For instance, he loved to tell the story of my sick cat, Sally, and how my mother told me one night that animals don’t need to go to the doctor because they get better on their own. Sally died the next day. And – so the story goes – later that year, the Soter family was driving some winding roads in Greece, and I got nauseous. I vomited, and then asked my mother if I should see the doctor. “No, you’ll get better on your own.” My father would always pause at that moment, ready with the punch line: “And Tommy said, ‘That’s just what you said about Sally.’”

My father was just as particular about punctuation and grammar (he once sent a long letter to a book editor, cataloguing all the grammatical errors and typos in a book he had), and loved composing letters skewering pomposity and what he saw as the misuse of the language. When working at my brother’s first bookstore in Chelsea, for instance, a customer asked him if the bookstore had any gay books. “No, but we have some slightly amused ones,” he replied.

Not surprisingly, my father could also be the most frustrating of men. I remember telling him about a movie I had just seen and enjoyed, The Great Debaters. “I don’t want to see it,” he said. “I know what it’s about. I’ve read about it.”

“But you haven’t seen it,” I insisted. “I have.”

Undeterred, my father said, “It’s just like To Sir, With Love, except set in the 1930s.”

“It’s not like To Sir, With Love at all,” I argued. Pointlessly, for my father had the last word: “Well, I wouldn’t know. I’ve never seen To Sir, With Love.” The conversation ended.

In fact, he always wanted the last word. On an emergency room visit to the hospital, I overheard this exchange between a nurse and a groggy George: “Mr. Soter, you have a temperature.”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“You do. I just took your temperature.”

“Well, if you knew why did you ask me?”

He could be frustrating in another way, too. He was often impractical, always thinking of things in grandiose terms. When I suggested he visit a Greek art gallery in Chelsea to see if they’d be interested in buying some of his Greek paintings or artifacts, he went to the gallery and came back with a new idea: he would ask them to give over a room to exhibit “The Soter Collection.” Nothing ever came of it – except that he created a “Soter Collection” showcase of his own in his last apartment.  George's 10-room apartment at 404 Riverside Drive.

George's 10-room apartment at 404 Riverside Drive.

How he loved remaking that place! He called it his “last hurrah,” the opportunity to transform what had been a rundown basement unit in my cousin’s century-old brownstone into something special. When she and I discussed its use for him, my cousin and I envisioned a touch-up, not a major renovation; George saw it in grander terms. And, although he was dying, he crafted a space that most everyone who saw it thought was amazing. It was a reflection of the man.

George was a genius at interior design. Once, not long after he had moved in to that last apartment, Luanne, his nurse, found him sitting, staring into space, “What are you doing?” she asked. “I’m picturing the room,” he said. And one could imagine him crafting the place in his mind. He had lived in three different apartments over the last decade (and before that, had been in one magnificent ten-room unit for 33 years). Each bore his distinctive stamp of organized clutter.

As much as my father loved his activities, he loved his family more. In September 2004, George, who had recently passed his 80th birthday, focused his never-flagging energy on a new endeavor: helping generate interest in Morningside Books, the bookstore owned by his youngest son, Peter, and his daughter-in-law, Amelia. To that end, he came up with a publicity gimmick that employed his favorite device – words – about one of his favorite habits – reading. George was a voracious reader; he finished at least two books a week, as well as countless magazines, The New York Times, and, of course, The New Yorker (which he read cover to cover, even in the dark days of Tina Brown). He regularly passed books on to his sons with the comment, "I think you'll enjoy this," although no one enjoyed those books half as much as George.

The new publicity device would be called Booknotes and it would turn out to be a duty he loved. Although the newsletter was only four pages, he turned it into something special, a kind of "Talk of the Town" for Morningside Books. There were announcements, mini-reviews of quirky books, author birthdates (with quotations), political commentary, and even his memoirs. Every month, George designed it, brought it over personally to Village Copier on 118th Street ("They're terrific," he used to say, in his typically enthusiastic manner), and doted over it like a parent with a special child. It's no wonder that he was pleased to receive a letter and photograph from a Booknotes fan. The letter was one of praise, which he was happy to receive, but it was the photo that particularly tickled him: it was a picture the writer had taken of her assembled collection of Booknotes, George's last major writing project.

Effie, with Nick

Effie, with Nick

Through most of his life, he was accompanied on his journey by Effie, his one and only true love. He was a Chicago-born Greek-American attending classes at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts as part of his army training. As he said to me years later, “I had heard there was a Greek girl at Clark, so I went up to her at a college dance and asked her to dance. She thought I was interested in her because her uncle [with whom she was living] owned a restaurant and was ‘wealthy,’ so she tuned me down. Again and again. And the cooler she got, the more interested I became.”

My mother’s resistance apparently didn’t last long. Soon after that, they were dating. Although they rarely talked about it, theirs seemed to have been a romantic, passionate love. Once, my mother showed me a shoebox full of letters from my father during the war. I looked at one: it was covered with handwriting on both sides, but the writing was only three words, a phrase repeated dozens of times: “I love you.”

When Effie contracted Alzheimer’s in the early 1990s, no one was more protective of her – or more frustrated. Before the illness, they always had a wonderful bantering, affectionate relationship. As the disease slowly stripped away her personality, however, you could see him cling lovingly, desperately, furiously to what was left. One reason he continued to play cards with her was because, as he himself admitted, that was the time when her old personality still asserted itself.

For each of them, the other was primary. When George was in the hospital once, all he asked about was Effie’s care; for her part, all she wanted to do was see him. When they met, however, none of this concern was evident. My father, with tubes in his mouth and nose, couldn’t talk; my mother, ever the chronicler of our lives, said, “Oh look at you. Let me take a picture.” George, ever conscious of his image, frantically waved his hands, “No!!!” After Effie and I left, she was more expressive of her true feelings: “It should have been me in there instead of him.” George and Tom, December 2008.

George and Tom, December 2008.

I always believed that my father didn’t want to finish tasks because having new projects kept him young, kept him going. When – because his own failing health made him unable to give Effie the care she needed – he finally managed to place her in a top-notch rest home, his greatest responsibility was over. He then completed the new apartment and, not long after that, became bedridden. He lingered there for about a month, welcoming friends and family that came to say goodbye, the charming host until the last. Then, on the evening of January 8, 2009, he died. He was 84 years old, although he once noted, “I have always been 37 even when I eye that old man in my shaving mirror each morning.”

But I still cannot get one image out of my mind. It was not too long ago, in that coffee shop we sat in so many times after my show. He was sitting opposite me, eating the chicken soup he always recommended (and which I always declined). And I sat there, knowing he was going to die soon and trying my hardest to memorize every line of his face, to remember that smile and that twinkle that seemed to define his essence. He noticed me staring at him and smiled that unforgettable smile. “I love you,” he said quietly, as though he had read my thoughts. It’s going to be all right, he seemed to be saying. You’re all going to be all right.

I love you, dad.

January 2009

A Dog's Life

CHARLIE'S GIFT

By TOM SOTER

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:681:]]

Charlie was the family dog. But he was widely considered my dog. He joined our family in the spring of 1972,when I was still living at home. And long after I had moved out, I still came by and took him for walks in the park. He always was ecstatic to see me, jumping up and down, his tongue hanging out of his mouth, his eyes glowing with happiness.

Or so I always liked to think. If I looked at it objectively, Charlie got excited when most people came by to call, and he usually seemed excited, much in the same way. But logic was never part of my relationship with Charlie. How could it be? He was a sweet, neurotic kind of dog, a golden-haired, perfectly proportioned cocker spaniel, big enough to be manageable but not small enough to be crushed underfoot or regarded as a toy.

He was not our family's first dog – although he seemed a distant cousin to him. That honor went to Eustie (or Eustice, whom my father may have named after Eustice Tilley, the fop on the cover of The New Yorker, a magazine he loved). Eustie was a cocker spaniel, too, and he looked a lot like Charlie. He had joined the family in the late '50s in Chicago, and even though he moved to New York with us in 1956, I was too young to actually have any memory of him. But I do remember the family story, often told, about how Eustie came to an end. Apparently, my maternal grandmother never liked Eustie, and thought having a dog around the house was unsanitary for children. Coming from Greece, where dogs often roamed free and were not often kept as pets in the city, she decided one day to let Eustie go. She let him loose at the door of our apartment building, and a few minutes later was sitting with my older brother, Nick, by the window. Before her (presumably) horrified eyes, she and Nick, aged about three or four years old, watched as Eustie attempted to cross the street in the park and was run over by a car. "Look, Yaya," Nick reportedly said (using the Greek word for grandmother), "That looks like Eustie!" Our dogs – except for Charlie – were never very lucky.

Our next one, a dachshund named Gretchen, lived with us for three weeks before she swallowed something that literally stuck in her craw and choked her. Sybil, a Kerry Blue terrier, lasted a lot longer, four or five years, before she was stolen by someone in the park. (At least we thought she was stolen; the romantic in me still likes to think that the dog – who liked to wander far afield and out of sight from us on her walks, just decided to keep on going on an adventure of her own.) Charlie was a gift from my mother to my father, a purebred, as my mom liked to say, but one who was so pure that he was very highly strung. As a puppy, he liked to chew on our bare feet as we sat at the kitchen table over breakfast, and as an adult, he had a strange obsession with my father's feet, often licking them – for the salt, my father used to explain, although I think it was because Charlie knew who was the boss in our family and was simply trying to toady up to him.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:683:]]

Charlie at the family dinner table, toadying up to the boss.

My father and I would often have disputes about Charlie. Not about his care and feeding but about more esoteric things. "He's having a bad dream," I would often say, when my father and I noticed him on his favorite couch in the kitchen, sleeping but growling at something going on in his dreamworld. "Dogs don't dream," my father would say, time and again. "Dogs don't think." It became a running gag with us, a kind of programmed mantra, in which I would argue for Charlie's thought process, and my father would take a Skinnerian position that dogs were just reactive. (It got to the point where I sent my dad a letter once, with a clipping for a book that postulated that cats had the ability to think. "Proof!" I wrote. "For cats maybe," was my father's reply, "but it doesn't say dogs.")

Certainly if Charlie could think, he would have thought twice about the present my father decided to give him one Christmas: all the food he could eat. Charlie loved to chow down, and he always ate his breakfast or dinner in the same way: fast. He could finish his half-a-can of horse meat in 30 seconds flat (we timed him once) and was usually still hungry after that (until we used a cast-iron bowl, he would kick his empty plastic supper dish around the kitchen with his nose to indicate that he was hungry – more proof to my mind that he could think). On Christmas day, sometime in the late '70s, my father said, "Charlie, we'll give you all you can eat." The dog eagerly downed his first half-can; then, with surprise and apparent joy, he went on to his second half-can, but by the time he had reached two-and-a-half cans, the formerly svelte dog was bloated and moving much slower. My mother said it was cruel, that he would eat until he exploded and even my dad had to concede that the gift had gone too far: that it had become too much of a good thing. We stopped the eating then. And Charlie was pretty miserable afterwards: because he was now so heavy, he could no longer jump onto couches the way he used to; he would try and then sit on the ground growling. We suffered, as well: usually taken for a walk three times a day, we probably had to take him out at least six or seven times because he had urgent business in the park.

Charlie loved the park. In those pre-leash law days, he liked to roam free – and would always wait to do his business until he had been out for a while since – no fool he – he must have recognized, through thought or instinct, that as soon as he finished what he was there to do, he would be taken home (this was especially true on shorter walks in the little park in front of our building, where we had to take him for quick pit stops before going to school). He loved the park because he loved the smells – and also the discarded food he would find. I would often rush up to him when I noticed he was hurriedly swallowing something, and I'd reach into his moth and pull a chicken bone from his mouth.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:682:]]

Charlie was often the cause of argument in our house, especially between my cousin Niko and me. Niko was staying with us while going to college and he was usually home in the afternoons. The dog needed to be walked three times a day and with my brother Peter available, nothing could be simpler: I took the morning shift, Niko had the afternoon run, and Peter took Charlie at night. But it rarely worked out that way. Although Peter was reliable, Niko often blew off his responsibility, which ticked me off no end. That was mostly because of the cruelty to the dog, but also because of the unsavory problems it created for us. When Charlie wasn't walked, he didn't seem to mind: he would just go to the long hallway in my parents' ten-room apartment and pee on the built-in cabinetry. (My father once joked that we should build a replica of the hallway out in the park, just to make Charlie pee more quickly out there.)

My brother, Peter, and I sometimes had disputes about the dog as well. One night, I was coming home and I noticed Charlie tied up outside The West End, a bar. In a self-righteous mood that does me no credit but was typical of the cruelty of teen-aged older brothers, I unleashed the dog and took him home.

"That'll teach Peter a lesson," I thought smugly. It was a lesson in sadism, I think. For my brother, who had just stopped into the bar briefly looking for someone, was shocked to come out and find that Charlie had been dog-napped. He searched the neighborhood frantically, most of the time in tears, before coming home to discover the dog safe and sound.

"I hope this teaches you a lesson," I said, sounding a little like Miss Gulch, the spinster schoolteacher in The Wizard of Oz. Peter started yelling at me and we both were soon shouting loud enough to bring my father out of bed. "What's going on here?" he shouted. We explained and my dad, in true Solomon-like fashion, scolded us both. "Peter, you shouldn't have gone into the bar and left the dog tied up. That was irresponsible. And Tom, you shouldn't have taken the dog. That was cruel." Peter sat in silence, accepting the verdict. But I tried to have the last word, "In my heart, I know that I was right," I said. "Who are you, Barry Goldwater?" my father asked.

Charlie lived with us for ten years, from 1972 to 1982. He started to show signs of being unwell – not eating his food for one thing – and Peter took him to the vet, calling me up to say, "It doesn't look good for Charlie."'[[wysiwyg_imageupload:684:]] The dog stayed with the vet for a week and seemed to show positive signs from the treatment – his kidneys were malfunctioning and the vet had to insert a tube in the dog's paw to flush him out twice a day – but we were told that the dog was miserable sitting in a cage all day. Better to let him go home and die.

I went and fetched him, and the doctor warned me: "He should be alright for a while, just don't take him for long walks that might tire him out." I brought him home, and then left for work. Peter arrived soon after and he was so ecstatic to see the dog that he took him for the longest of long walks, running him up and down hills with joyous abandon. Until the dog collapsed. Peter thought he had killed him, but Charlie had just fainted. He would faint often after that – seemingly normal, and then passed out on his side.

The doctors had given him a week to live Charlie outlasted their predictions by six months. My mother would take to introducing him to our guests as "Charlie, our dog who is officially dead." The vet saw him frequently, my dad reporting, "Some days the dog feels good, other days not so good. Just like the rest of us." But the poor little dog – who it turned out also had a heart murmur – couldn't outrun his fate for long. One day he just stopped eating, and then didn't even want to go out. Listless and quite unlike himself, he sat curled up in a ball, unwilling to move or speak. Sadly, my father and I took him in a cab to the vet.

"What if we have to put him to sleep?" I asked my father. "He trusts us. And we're taking him to die."

"He trusts us to do what's right for him," said my father gently, no longer arguing about whether Charlie could think or not. "He trusts us not to let him suffer."

Charlie, with TS

A few days after that, I talked with the vet who said that we should put the dog to death. "He is suffering, I think. But we can talk about it when you get here." I agonized about the decision on the way over, but ultimately I didn't have to make it. For Charlie, just moments before I arrived, had stood up straight and tall, let out one yelp, and then collapsed in a heap, dead. He apparently didn't suffer much – and I always think he didn't want me to suffer much, either. For after a lifetime of my taking care of him, Charlie had done his best to give me one final gift, and he took care of me.

July 12, 2009

Dear Mr. Inc.

FIGHTING THE LOST CAUSE

George, between battles.

By TOM SOTER

The envelope looked familiar yet unfamiliar. It was apparently something I had mailed that the post office was returning as undeliverable. Curious, I opened it to find that it was a letter with important information about my mother that I had sent to her nursing home – nearly a year ago. And it was being returned now?

Angry, I called the post office's customer service number. After wading through the various recorded keypad choices, I finally got a human. Human, yes, but not very humane. After I explained the situation, she said, in an impersonally sympathetic voice, "We're sorry for the inconvenience, sir." I exploded. "Inconvenience! It's outrageous!" Noting that the destination for my letter was only 50 blocks away, I exclaimed, in an attempt at wit, "I could have delivered my letter faster if I had crawled on my elbows."

My joke was as ridiculous as the whole situation – and I pursued it through two more equally frustrating phone calls with two more post office representatives. "Why do you waste your time?" a colleague at work asked me when I told her the story. Why indeed? Why take on these big, impersonal corporations and expect them to act any differently? Was it my inner Jimmy Stewart, challenging the powerful as his character, Jefferson Smith, did in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), where he famously said, "The lost causes are the only ones worth fighting for?"

Perhaps. But I think it had more to do with my father, George. He was a fabulous letter writer, and he was often at his most inspired when he took on chain stores, big corporations, and other faceless entities with which he was forced to deal.

A typical letter was one that he sent to the Eddie Bauer clothing store chain in 2002. "First off," he began, in his typically straightforward manner, "in my two conversations with your Eddie Bauer representatives (in my estimation, mistakenly labeled 'customer service') I made no inquiry regarding bank fees which your form letter suggests I did." He goes on to recount his tale of woe, as though he were Dickens writing about Pip in Great Expectations: "To trace the history of my having an account with your company ....[it] began when a business associate who was wearing a navy blue linen shirt that I admired directed me to your company where he had bought it. Alas, by the time in late August that I finally hit the Eddie Bauer store on Broadway and 68th, linen shirts were long gone. But, being a happy shopper, I looked around and found another handsome shirt – a sort of brushed denimy cotton, priced around $25. When I brought it to a salesperson, he asked if I had an Eddie Bauer charge [card] and then, when I said I would pay cash, suggested that, if I opened a charge [account] that day I would automatically receive a discount. I was hooked. The discount was relatively miniscule, but I liked the merchandise in the store and since I had three grown sons and any number of grown nephews for whom I purchased gifts, an Eddie Bauer Charge sounded like a good idea. Not so. I did the paperwork and went off with my lightly discounted denimy blue shirt."

He went on to explain that "shortly after the above, in mid-September, I moved – after forty years at one address and after a lucrative sale of a ten-room apartment on Riverside Drive – [and] as a result of that move experienced an unusual disruption of my mail delivery (I received no mail from September 6 through September 26 even though I had filed a change of address form in a timely manner).

".... among the many pieces of tardy mail I received was your first bill for that nice blue shirt and, that once I found it in the turmoil of the move, I immediately sent off a check even though the payment due date had passed by several days.... I was shocked to discover on my next bill from your company that my late payment for that slightly discounted handsome blue shirt was for more than the original cost of the shirt.

"It was then that I telephoned the customer service number with a request that my charge account be immediately canceled since I had no interest in being associated with a company engaged in such usurious fiscal practices. [The customer service representative], anxious to maintain a new (though albeit late-paying) charge customer suggested that the way to proceed was to immediately pay the minimum balance on the new bill and that she would, given the circumstances, convey my distress to the proper authorities and, though she made no concrete offer of reimbursement or even of review, she optimistically encouraged this line of action. So, I paid the $35, which, then, it turns out became a first installment on the purchase of my $25 shirt. And, I must admit, I half-expected that, soon, I would receive, at least, a form letter of apology from some Eddie Bauer representative. After all, Eddie Bauer was a Class Act not a Canal Street fly-by-nighter.

"After mailing a payment to you yesterday for my last bill from you ($54.93), I calculate that that nice blue denimy $25.00 shirt has now put me out for $115.55. If this is an example of your come-on discount, how would you identify a scalping operation?

"I hereby ask you to cancel my charge with your company and reqest that you send me no literature, catalogues, etc. Unfortunately, what you won’t be able to cancel is the word-of-mouth of this hapless former customer."

George in his 80s.

George in his 80s.

George often threatened these impersonal corporations in the only way he knew how, with the loss of his business and with his powerful word of mouth. (He never minced words: once, after spending over two-and-a-half hours sitting through Apocalypse Now when it opened, he walked down the long ticket-buyers' line, saying to people, "It's terrible, don't waste your money!")

His letter to Rite-Aid in 2004 followed this same pattern: "I am an 80-year-old man, principal caregiver for my wife Effie Soter who has Alzheimer's," he wrote. "For the past decade, I had been ordering my prescription drugs via the AARP mail service but, about a year ago, I found that it was more convenient to use your pharmacy at the above location since I would then no longer need to depend on mail delivery. I have since used this pharmacy for all our household drug needs, finding the telephone refill service particularly helpful.

"On Friday, November 18, I tried to use the call-in service for a refill on my wife’s 10 mg Ambien pills; the bottle indicated that there were two refills available. I repeatedly called from 8:00 am until I left my office around 3:00 pm and was unable to complete the call (I later was told that the phone service had been inoperative that day). Since the medication was extremely important – my wife is subject to uneasy sleep and nocturnal wandering – I had the refill bottle hand-carried to the pharmacy at 6:00 pm and was told it would be ready in an hour. Although, when our son went to pick it up at 10:00 pm and was told with a disdainful and unaccommodating manner that he would have to wait another hour, that is not the main purpose of this complaint. That follows.

"At 11:00 pm, I received a call from the on-duty clerk who announced that our prescription was 'unfillable' despite the Rite Aid-typed 'two refills' on the label. He went on to offer a surly explanation that Dr. Braun who had provided the original prescription had erroneously (and illegally?) prescribed 60 tablets, which the pharmacy had filled with 30 tablets on the original pick-up and one subsequent one (and about which substitution neither I nor the doctor had been informed) and as a result there 'were no refills left.' (On whose authority did a part-time night duty clerk countermand Dr. Braun’s prescription instructions?)

"This surprising and unclear arithmetical explanation was of no use to me for my immediate problem – how do I get along on the Saturday/Sunday week-end without the necessary Ambien?

"It seems to me," said George, still searching for humanity among the inhumane, "that a responsible professional pharmacist would have done the following: if Dr. Braun had, indeed, made an error, either he or I should have been informed at the time of the original prescription order; failing that, the clerk, on Friday the 18th, should have telephoned me, early in the evening, to report that the prescription 'was unfillable' so that I was prepared and could make some rectification (such as a 'borrowing' of two pills from another Alzheimer patient’s caregiver – which was not possible at midnight on short notice).

"Because of this compounding of failures by your pharmacy staff, I was faced with the drama and painful mental anxiety of two nights without the necessary medication and this, after a 12-hour day of continuous frustration in trying to place the refill order. When I asked the manager of the Broadway store the name of the pharmacy manager there so that I could direct this complaint, she told me the name was 'Stacy' and that she didn’t know her surname but 'that it was Chinese.'

"As a result of this exceedingly unhappy long-day experience, I will no longer be using your pharmacy – nor any other of the services of your stores. And, despite my age, I have a big mouth and a large group of acquaintances, to whom this tale of Rite Aid professional non-service will be a much-repeated anecdote."

But the exchange my father had with The New Yorker (yes, The New Yorker) was his most personal and heartfelt. As a decades-long fan of the publication, he was particularly upset by his impersonal treatment at the hands of the magazine, which he had always equated with class and style. Alas, even the most classy can take a fall.

"Dear, dear New Yorker," he began in a 2007 letter, as though he were writing to an old friend or wayward lover and not the subscription department, "I write this with mixed feelings – frustration, anger, disillusionment, annoyance, abandonment, shock.

"Dear, dear New Yorker," he began in a 2007 letter, as though he were writing to an old friend or wayward lover and not the subscription department, "I write this with mixed feelings – frustration, anger, disillusionment, annoyance, abandonment, shock.

"In early April, I ascribed the first absence of my New Yorker from my Monday mailbox to a probable postal error; then, for the second week's absence, to the possibility that the missed issue had been one of your periodic and periodically annoying 'double issues,' and that this accounted for no issue this week, again. By the third mailbox absence, I was having acute New Yorker-deprivation feelings – how would I know what was happening in the theater, at the movies, in Washington, in the world? (I bought a copy of the third absent issue at the local newsstand, having stolen the former week's copy from one of my sons – I have three, and for many years they each have been gifted by me with their own subscriptions.)

"So, I called the circulation department and spoke to a young woman about my missing copies. She coolly reported that my subscription had expired, citing an April date. When I complained that I had received no warning notice – card, letter, or e-mail–about the imminence of such expiration, she asked me to wait a moment while she consulted the record. Shortly after, she came back on the line to report that I was right, there had been no warning notice sent. She reported this failure coolly, without any explanation for such a lapse, nor even the suggestion of an apology. I asked her, testily, to renew my subscription

A New Yorker-style cartoon, done by George in the 1950s.

A New Yorker-style cartoon, done by George in the 1950s.

"Don't you keep any sort of a file on your subscribers?" he asked, both irritated and plaintive, wanting some acknowledgment of his devotion and dedication to his much-beloved magazine. "[Isn't there] some kind of a data bank indicating the history of a multi-decade (such as my) subscribership? Nor some record of subscription gift-giving by subscribers? (My annual list has, for many years, included, in addition to my three sons, friends in such distant places as California, Greece, France, and England.) Is such data of no value to you?

"Of course, even if you had such records, they would hardly do more than imply my personal lifetime New Yorker relationship: being an enduring reader/fan starting in a 1930s Chicago high school English class; chasing after the armed forces mini-versions distributed to GIs in WW II; in the mid-40s, taking long weekly bus treks to Detroit's Book Cadillac Hotel newsstand, seemingly the only outlet in that culturally bereft city; once, at a flippant age, even toying with filling out some form, by writing 'New Yorker' in the space asking for 'religion'; still stubbornly continuing to subscribe during the odd Tina Brown years, though not as contentedly; and, in a four-decade career in the advertising business, using the New Yorker as the lead vehicle for advertisers, among them, Standard Oil, Renault, Air France, IBM, Tiffany, Shumacher, even, such unsophisticated ones, as Trump.