James Bond

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:60:]]

.

.

.

Austin Powers

AUSTIN POWERS

AUSTIN POWERS

By Tom Soter

from MOVIE TIMES

It’s shagadelic, man.

Austin Powers, the international man of mystery, the secret agent who out-spoofed James Bond and snagged a boffo box office, will return on June 11 in The Spy Who Shagged Me. As he did in the initial entry, Mike Myers plays both Powers, the hip spy with the bad teeth and groovy sixties outlook, and Dr. Evil, the bald-headed nemesis who spent seven years in “evil medical school” (and was inspired by 007 bad guy Ernst Stavro Blofeld).

The first movie, a surprising success, tapped into a young audience’s fascination with the psychedelic sixties and sight gags and an older audience’s nostalgia for that Bondian age. Although Powers is no super-spy in the Sean Connery style he captures a key quality of Connery’s Bond: self-mockery. Powers is a super-schmiel, a kind of Maxwell Smart-Inspector Clouseau-007 hybrid, whose appeal is in his outlandish, unknowing nerdiness. He is a suave schnook. And the Powers movies hark back to that Bond super-parody, Casino Royale: short comic bits and gags that depend a great deal on the audience’s knowledge of spy movie cliches.

The plot for Spy Who Shagged Me could come right out of The Avengers (the TV show, not the movie): Dr. Evil returns to 1969 after stealing Austin Power's “mojo,” the the life force of every secret agent. The result: Powers can't make it with the chicks. The superspy and new squeeze Felicity Shagwell (Heather Graham) zoom back in time to battle Evil and retrieve the mojo.

Like the first movie, 007-style puns predominate (Kristen Johnson plays Ivana Humpalot), along with celebrity guest shots (Burt Bacharach, Elvis Costello, Willie Nelson). The movie also features the same endearingly silly dialogue (“I shagged her. I shagged her rotten, baybeee”) and visual homages to sixties pop chic.

Will the flick make a billion zillion dollars? Do you need to ask? Yeah, baby! Groovy!

Bond Paperbacks

SELECTED BOND NOVELS IN PAPERBACK, 1950s-2011

I'm a collector. Not a ticket collector or a collector in the Terence Stamp sense, but a collector of books, DVDs, and other odds and ends (others might call me a pack rat, but that's another story). One thing a collector likes to do is share his collection with others. Here

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:370:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:371:]]

are some paperback novel covers from my James Bond collection. More to come. June 24, 2011

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:372:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:373:]]

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:368:]]

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:369:]]

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:361:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:362:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:363:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:365:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:366:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:367:]]

Bond Paperbacks 2

COLLECTORS' CORNER

BOND FILM TIE-INS

PAPERBACKS, FRONT COVERS

More from my book collection. June 25, 2011.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:376:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:377:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:378:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:379:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:380:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:382:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:383:]]

Bond Paperbacks 3

COLLECTORS' CORNER

BOND FILM TIE-INS

PAPERBACKS, BACK COVERS

More from my book collection. June 25, 2011.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:392:]]

Bond Paperbacks 4

COLLECTORS' CORNER

BOND PAPERBACK BOOK COVERS

More from my private collection. June 26, 2011.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:401:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:402:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:403:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:404:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:405:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:406:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:407:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:408:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:409:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:410:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:411:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:412:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:413:]]

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:394:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:395:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:399:]][[wysiwyg_imageupload:400:]]

James Bond 1

007: His license to thrill replaced by gimmicks

By TOM SOTER

from THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

April 29, 1977

Sean Connery in You Only Live Twice.

Sean Connery in You Only Live Twice.

Since the first James Bond film was released in 1962 there have been nine films chronicling his adventures. That's about five too many and is sadly indicative of the old saying "nothing succeeds like success" which must motivate Hollywood producers. In Bond's case, the success is still there, but the reasons for it have now become as obscure as some former presidents.

When Doctor No, the initial 007 movie appeared, it was moderately successful. From Russia With Love did much better and Goldfinger was a runaway success, becoming one of the fastest grossing films in history. When one sees it today, it is still remarkably fresh and entertaining and manages to make its successors seem shallow by comparison. It epitomizes all that is good and bad in Bond and, also, the reason why he finally had to fail.

In it, we· are given the fantasy-like violence that was to become a 007 trademark (beginning with a pre-credits mini-adventure involving Bond, heroin-flavored bananas, and a rubber duck) as well as menacingly unreal villains withnames like Auric Goldfinger and Pussy Galore. We are also presented with preposterous gadgetry, of which Bond's Aston Martin, the car that can do anything, is the best known example.

This mechanical versatility is what ultimately spelled the end for the series. Feeling that bigger must be better and that the best way to improve future films was to increase the gadgetry, later movies like Thunderball and Live and Let Die were literally buried in gimmicks, and. in the process, the two things that made Bond unique, that odd mixture of spoof and menace were lost.

In Goldfinger and From Russia With Love, the tension is created by inhuman villains that seem capable of beating 007. The mute Korean Oddjob with his steelrimmed, frisbee like hat, and the silently menacing Red Grant who hovers in and out of Bond's path like a ghost are dehumanized by their silence and thereby act as good foils to the super, but still human, secret agent.

And Bond kept that humanity, and our sympathy, by his ready wit and his unwillingness to take anything too seriously. He kept the dehumanization and the violence at a distance by his humor; we constantly knew it was make-believe and therefore could enjoy it.

Sean Connery was uniquely suited for his role. His thick Scottish agent seemed at variance with the David Niven-like hero Ian Fleming envisaged, and thus made him the perfect personification of the comic/serious duality of the series. It also helps explain why his successors, George Lazenby and Roger Moore, both touted as "more in the Fleming image" have been unsuccessful. Fleming's character is not very interesting. He is a somber figure who rarely sees the humor of his adventures. Connery could and because of that gave the series the focus it needed.

Connery in Goldfinger.

Since his departure, however, the Bond films have become little more than assembly-line productions with audience programming being the primary concern. If a car chase worked well in one film, for instance, there will be three chases in the next one. This technique might be logical, but it is also tedious, making Bond films the victims of the very dehumanization which their hero had previously fought against. It has come to the point where anyone can make a Bond film as long as he knows what audience-reaction buttons to press.

Then why do people attend them? The simplest answer would be nostalgia for a time when the world could be broken down into stylish bad guys and good guys. The sad thing is that the Bond films don't even offer that anymore. They are no longer stylish and are now too predictable to offer any real escape.

Which is too bad, and anyone wanting to see what I mean, or hoping for a break from studying, can journey down to the Carnegie Hall Cinema on May 6th, when Goldfinger and Doctor No will be playing. If nothing else, they offer proofof how far we haven't come in Bond films since 1964.

James Bond 1983

from DIVERSION, June 1983

Roger Moore vs Sean Connery: friendly duel.

To some of us, Sean Connery is and always will be the only James Bond. Notwithstanding that fact, many moviegoers have settled for Roger Moore's pallid interpretation since Connery abdicated the film role, in 1971; indeed, Moore's most recent Bond films have grossed between $150 and $200 million each.

But now a cinematic showdown, as unusual as any 007 has faced in 21 years on the screen is in the offing. There will be two Bond movies released this summer: Connery returns to the screen as Bond in Never Say Never Again, and Moore essays the secret agent once again in Octopussy. The big-screen Bond is based on the hero of the highly successful series of books created by Ian Fleming, an upper-crust former British naval officer who had been involved in espionage activities during World War II. Fleming wrote his first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1952, drawing on his wartime intelligence work and his skills as a journalist (he had covered Moscow spy trials in the 1930s and later worked for the Sunday Times of London) to create the suave and dangerous secret agent with a license to kill.

Although the book sold well for a first novel and received good notices, a film sale failed to materialize. Instead Fleming sold the rights in 1954 to CBS, which produced an unsuccessful television version of the story with Barry Nelson as an American spy, Jimmy Bond. Fleming wrote another script about a Bond-like figure that never made it to the TV screen (although Fleming salvaged the plot for his novel Doctor No), and did treatments for a CBS TV series about Bond that also was never made. It was not until 1963, one year before his death, that Fleming found the tremendous success he was looking for, with the film version of Doctor No, starring Sean Connery. By then, of course, President John Kennedy had told the nation that he loved the Bond books, an endorsement that certainly didn't hurt the secret agent's Image.

Producer Albert R. Broccoli, who with Harry Saltzman optioned the rights to all the Bond novels (except Casino Royale) in 1961, began what has become the most successful film series in history. By 1964 Bondmania was at its peak. Goldfinger, the third Connery 007 picture, grossed $10,374,807 in 13 weeks of U.S.Canadian release. Crowds clamoring to see the the film were so large that the DeMille Theater in New York City opened its doors 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for showings.

Taking Stock Of Bond

Bond toys, gadgets, and board games flooded the market. There was a model of OO7's Aston Martin, a spy attache case, a toy figure of Connery with tiny daggers that shot out of his shoes, 007 toiletries that promised to "make any man dangerous," even a rock song featuring the lyrics "My baby went and fell in love with 007."

There was also a rash of highly derivative spy movies (The Ipcress File, Our Man Flint) and television series (Secret Agent, The Man From U.N.CLE.), but none could match the success of the Bond phenomenon.

Connery bowed out of the series for the first time in 1967 (George Lazenby replaced him, as one critic put it, "the way concrete fills a hole") but returned in 1971 to make Diamonds Are Forever, a movie that broke records everywhere. In 12 days, it took in $24,568,915 at cinemas around the world. Despite that success, Connery announced that he would never do another Bond picture, and Broccoli turned to Moore, who had starred in the long-running television series The Saint. Although many Bond fans found Moore a weak substitute for Connery, the Moore Bond movies have garnered ever-increasing box office receipts.

Maude Adams and Moore in Octopussy.

Maude Adams and Moore in Octopussy.

The Plot Thickens

How and why Connery has come to reprise his Bond role one more time for independent producer-director Kevin McClory is a somewhat complicated story. McClory had convinced Fleming to let him bring Bond to the screen as early as 1958. Discarding the books as source material, McClory, Fleming, and veteran screenwriter Jack Whittingham concocted a screenplay called James Bond of the Secret Service, involving nuclear terrorism and a Bahamian-based villain named Largo. When that project fell through, Fleming adapted the story for the film Thunderball (starring Connery). McClory charged plagiarism and sued. The case was tied up in the courts for three years but resulted in an agreement between Broccoli, Saltzman, and McClory whereby all three of them coproduced Thunderball. Coming at the height of the Bond craze, the movie was a smash hit, collecting $28 million in U.S. rentals, which made it the most successful Bond movie until Moonraker in 1979. McClory's involvement might have ended there except for a clause in his agreement with Broccoli and Saltzman that allowed him to remake Thunderball ten years after the date of its initial release (1965). In 1976, McClory announced preproduction plans for the remake, saying he had a screenplay by spy novelist Len Deighton, Connery, and himself, but Broccoli took McClory to court and the production was stymied for six years. Then, last year, Jack~ Schwartzman took over the project (with McClory as executive producer), now called Never Say Never Again. The old script was junked, and a new one was written by Lorenzo Semple Jr. (Three Days of the Condor). Irvin Kershner (The Empire Strikes Back) was hired to direct.

Dr. Maybe

Connery's involvement had begun in 1975, when McClory invited him to work on the screenplay for the remake of Thunderball. "It was clever of McClory to involve Sean," one observer noted. "Once Sean wrote it, he startedto care about the character he'd previously got fed up with playing."

Back in Bondage: Connery with Klaus Maria Brandauer in Never Say Never Again.

Connery told the press that he thought it would be fun to go back and play Bond after ten years because "he would be different, that much more experienced, older, and I would find a different vein of humor and do things that are more difficult to do and play." The new producers' approach was to have Connery play the character at his own age, which is now 52, "and not go on pretending Bond is still 32."

Never Say Never Again (a title that purposely recalls Connery's earlier insistence that he would never return to the screen as Bond) is intended to update Bond in much the same manner that John Gardner's recent 007 novel License Renewed brought the print Bond into the 1980s. Bond is no longer a youthful agent; he is a man slightly out of step with thc times, an antihero of sorts, which is a canny move considering that part of Bond's carly appeal had been his iconoclasm.

Now, however, antiheroes are the norm, and the new Connery approach clearly worries producer Broccoli, whose own Moore Bond remains proestablishment and who has said that the approach contcmplated in Never Say Never Again might affect Bond's following with millions of fans who still want clear-cut heroes.

For his new Bond movie the producer is taking no chances. Octopussy is nominally based on an Ian Fleming short story that was published posthumously. But because Bond barely appeared in that story-he turned up at the end to arrest the villain, who, in fact, had already been killed by his pet octopus, Octopussy-Broccoli abandoned the original completely. The film version features the usual 007 ingredients: a larger-than-life villainess named Octopussy, a menacc that threatens the world, and a grab bag of incredible gadgets.

Contrasting Styles

Who will win the cinematic confrontation this summer'? If brand loyalty is the key, Connery may have the edge. "I was standing in the back of Graumann's Chinese [Theater] when Diamonds Are Forever opened," recalls Tom Mankiewicz, who was co-screenwriter on that film. "And at the beginning of the film, when Sean says, 'My name is Bond. James Bond,' there was such a roar from the audience. It was like welcoming home a son from the war. There's a great loyalty for him, and the picture was a smash partly because people just wanted to see him again."

Connery may have the edge for more reasons than nostalgia. As a pcrformer, he is uniquely suited for the Bond role. His Scottish acccnt seems at odds with the suave English hero Ian Fleming envisagcd, which gives him the proper balance between comedy and seriousness. Moore, touted as more in the Fleming image, does not work as well, partly because he is so Flemingcsque. Moore's Bond scarcely sees the humor of his situations, while Conncry's recognizes the humor without losing sight of thc inherent dangers. Connery also gave the scries the focus, the hard dramatic cdge, it needed.

Penultimate film: Connery and Jill St. John in Diamonds Are Forever.

"I start with the serious and try to inject as much humor as I can to get a balance of ingrcdients," Connery said in an interview with Time. "Roger comes in the humor door, and I go out it."

"Sean and I saw him differently," says Moore. "When I started, Bond naturally took a much lighter tone. After all, who could take me seriously as a spy'r"

The stakes on both Bond movies are high: each film has run up a $2.5 million-plus budget. The films will also be competing with Return of the Jedi, a Jaws 3-D, the sci-fi Krull, and other big films for box office dollars this summer. Will there be enough Bond fans to make Bond's double return doubly successful'? If not, may the best Bond win.

James Bond 1987

The Living Daylights

1987. Timothy Dalton, Maryam d'Abo, Joe Don Baker, Desmond Llewelyn;' dir. John Glen. 130m. (PG) Hi St cc $89.98. CBS/ Fox. Image: good.

The images are evocative: an Aston Martin, a martini shaken not stirred, a grim smile, a tuxedoed man saying, ·'Bond. James Bond." It's all part of a ritual that seems as old as movies themselves. Dr. No appeared in 1962, although Ian Fleming had introduced the world to secret agent 007, the man with the license to kill, in the 1953 novel Casino Royale.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:528:]]

Bond has survived the death of Fleming, the departure of Sean Connery and the ignominy of Roger Moore. He has turned from tongue-in-cheek suspense to tonguein-cheek cartoon without losing a dollar at the box office. The 007 movies have netted a total of $2 billion in ticket sales and, if The Living Daylights is any indication, the series could earn a lot more in years to come.

The producers c;m thank Timothy Dalton, a Shakespearean actor whose clipped delivery recalls Patrick McGoohan's but whose dark good looks and no-nonsense style are strictly his own. This 007 is grimly serious, a scowling engine of action who is not only as exciting as Connery but gives Bond movies the focus they lacked for over a decade.

If only they had tightened up the plot. This one is so complicated it collapses under the weight of its own ingenuity. The diamond-smuggling tale involves enough double-dealing to confuse Ollie North.

Yet the familiar attributes are so reassuring: John Barry's rousing score, exotic locations (Afghanistan, Austria, Tangiers), incredible stunts (a car driving into a moving plane). There's hokey dialogue ("Don't think-just let it happen") and an incredible climactic battle with exploding stunt men falling all over the place. The Living Daylights isn't a great movie-but it is a Bond movie. And the best Bond in years. Ejector seat, anyone?

64 VIDEO MAY 1988

James Bond 1989

Sean Connery in Doctor No

Sean Connery in Doctor No

from DIVERSION, MARCH 1989

It's classic Bond-James Bondfrom the equally classic Goldfinger. And although the film was first shown 25 years ago to audiences who attended at record-breaking levels (it earned $30 million in six months, with many theaters staying open 24 hours a day to satisfy demand), no one seems to have tired of it, or of Bond, the secret agent with the 00 prefix, and the license to kill.

During the 1970s, Goldfinger and its successors repeatedly racked up profits in theatrical reissues and network television screenings. In the early 1980s, videocassettes of the films from CBS/ Fox Home Video consistently sold out. And since the first film, Doctor No (1962), the 17 Bond movies have earned $2 billion in ticket sales. The Living Daylights, the 1987 installment, garnered $11,051,284 in its first three days of release in the United States, the highest three-day gross in Bond history.

Timothy Dalton as 007

And there seems to be no end in sight. Filming for Licence to Kill, the 18th Bond movie, has just been completed in Mexico, in time for release this summer. On the video front, MGM/ UA has remastered and repackaged 13 of the earlier films, while Amvest Video has unearthed a rare early television production of "Casino Royale," the first Bond novel. On television, ABC has rerun some of the movies as many as eight times each since 1972. And in print, novelist John Gardner taking over for Bond creator Ian Fleming, who died in 1964, has written six bestselling 007 novels, while others have offered such volumes as The James Bond Bedside Companion, The James Bond Films: A Behind-the-Scenes History, Bond and Beyond, and Nobody Does It Better.

Amazing? It certainly is to onetime 007 Sean Connery, who noted in 1983: "It's kind of odd that this character should have lasted so long."

Fantasy Figure

Bond was born in 1953, a male fantasy created by Fleming, a middle-aged ex-journalist. Casino Royale, the first of 12 novels that Fleming would churn out before his death, introduced the hero as a dark, brooding, and fallible secret agent. It was wish fulfillment of the most basic kind: Tough guy Bond overcomes almost insurmountable odds (and the wiles of a treacherous woman) to save the day. Adding to the appeal were Fleming's clever embellishments-vivid descriptions of food, drink, and women that, he claimed, "reassure the reader that both he and the writer have their feet on the ground in spite of being involved in a fantastic adventure. "

Even the choice of Bond's name--taken from the real-life author of Birds of the West Indies-was a deliberate attempt, said Fleming, to let readers "put their own overcoats on James Bond and [build] him into what they admire. . . . When you think of it, it is a dull name. I could have called him Peregrine Carruthers, or something lush-sounding, but then I would have defeated my aim of making him credible. I wanted the blankest name possible."

You Only Live Twice

Bond soon took on a life--and followers-of his own. John F. Kennedy named From Russia with Love as a favorite novel; Raymond Chandler called Fleming's work masterly; and British author and critic Cyril Connolly wrote that Bond "makes everyone go back to prep school. . . . In the most horrible Bond episode, one still hears the voice of a small boy in a dormitory describing Chinese tortures."

The secret agent-who reached the peak of his popularity in 1964-65 soon came to be identified with the lost glories of J. F. K.'s Camelot. Like Kennedy, Bond on-screen was seen as youthful, glamorous, witty, and above all, stylish. Said Connery: "I saw him as a complete sensualist, his senses highly tuned and awake to everything. He likes his wine, his food, his women. He's quite amoral. I particularly liked him because he thrived on conflict. But more than that, I think I gave him a sense of humor."

The films were loaded with novelties. Where else could you find a bad guy with a razor-rimmed bowler hat that, when hurled like a Frisbee, sliced off people's heads? Or a woman with a poisoned, retractable spike in her shoe? Or a hero who wears a tuxedo beneath his underwater wetsuit? Only in a Bond film would a villain make his headquarters in a volcano or use piranhas to eliminate superfluous employees. And only Bond himself could get away with the outrageous puns and weak jokes tossed off after "certain" death.

Above All, Style

Bond had style in everything: his suits (Savile Row); his drink (a vodka martini-"shaken, not stirred"); his cars (Aston Martin, Lotus, Bentley). The various Bond incarnations – Connery, David Niven, George Lazenby, Roger Moore, and most recently, Timothy Dalton – have all added their own personal touches to further enhance the Bond mystique.

George Lazenby as 007

George Lazenby as 007

And those villains: Auric Goldfinger, who wants to blow up Bond and Fort Knox in one shot; Ernst Stavro Blofeld, who tries to start World War III in three different films; and Francisco Scaramanga, the man with the golden gun (and three nipples), who enjoys a cool murder before making love.

Early on, coproducers Albert "Cubby" Broccoli and Harry Saltzman realized that the fans would return if the stunts and effects continued to outdo themselves. Explains former Bond screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz: "The minute Bond pressed the ejector seat [of the Aston Martin in Goldfinger], and the audience roared, the series turned around. The audience saw outlandish things they had never seen before, and the natural response of anybody-a writer, a filmmaker-is to give them more of what they want."

From cars with ejector seats to a helicopter that could fit into a suitcase, the cinematic Bonds, with the help of the scientist "Q" and his laboratory, never failed to come up with the stateof-the-art in fantasy secret-agent gear. Ideas came from everyone: Writers, camera crews, production designers, even fans, and all were sifted by Broccoli and Saltzman, the mismatched godfathers of 007.

"Cubby's life is those films," says Mankiewicz. "He loves working on them. Harry is just a natural wheelerdealer; he is so mercurial. He would have twelve ideas in ten seconds. And nothing is big enough for Harry. When I was working on Diamonds Are Forever, we had a problem with the script, and Harry said to me, 'What's the basic threat here?' I said, 'Blofeld's going to destroy the world.' And Harry said, 'It's just not big enough.' "

007 (Sean Connery) meets Pussy Galore (Honor Blackman) in Goldfinger.

The "Bond formula" is the outgrowth of a collaborative process. First, the pre-credits sequence typically involves 007 in a wild mini-adventure that has little to do with the main story. In Goldfinger, for example, he blows up a heroin factory and uses a fan to electrocute a bad die in a bathtub. Then Bond is called onto the case proper-largerthan-life bad guys soon try to kill him; he meets the heroine; he encounters the main villain and learns of his diabolical plans; he is captured and taken to the bad guy's secret headquarters; using gadgets, wits, and the help of the "Bond girl," 007 escapes, destroys the bad guy and/or his headquarters, and makes love to the heroine.

This had become so formulized over time that by 1967, Roald Dahl was told only six things when called in to write You Only Live Twice. "Bond had to have three women in the film," said Dahl. "The first one would get killed, so would the second, and the third would get a fond embrace in the closing sequence. And there should be a great emphasis on funny gadgets and lovemaking."

First Bond Girl (Ursula Andress) meets Bond's dad (Ian Fleming).

He was right. The Bondwagon rolled on, outlasting Saltzman (who left the partnership in 1975), television imitators ("The Man from U.N.C.L.E.," "I Spy," "Mission: Impossible," "Honey West"), film competition (Our Man Flint, The Ipcress File, The Silencers), promotional tie-ins bordering on overkill (007 cuff links, a lady's nightgown with 007 sewn in the hem, Bond Bread advertised by Secret Agent James Bread; a toy figure of Bond with tiny daggers that shot out of his shoes), and casting ineptitude (former car salesman and model Lazenby as Connery's first replacement in 1969's On Her Majesty's Secret Service; one critic observed he filled the role "the way concrete fills a hole"). Somehow, though, Bond once again beat the odds. The 25th-anniversary film, The Living Daylights, introduced a new 007, Timothy Dalton, and a new approach. "In order to keep our originality," current director John Glen noted, "[we] felt we had to get back to real action and people." Added Dalton: "My approach is to humanize the man much more, Bond is not a superman, he is an ordinary man. He's a lapsed idealist who is rediscovering what is right or wrong, what is the truth."

So Bond has come full circle, and the old appeal returns for a more gilded age. J.F.K. and Fleming are gone, and Connery and Moore have since moved on. But 007 endures. "The basic success of Bond," explained 12-time 007 screenwriter Richard Maibaum, "is [that of] a ruthless killer who is also St. George of England, a modern-day combination of morality and immorality. In the age of the sick joke, it clicked." Or as Malcolm Muggeridge wrote in 1965: "Fleming's squalid aspirations and dream fantasies happened to coincide with a whole generation's. He touched a nerve. The inglorious appetites for speed at the touch of a foot on the accelerator and for sex at the touch of a hand on the flesh, found expression in his books. We live in the century of the Common Bond, and Fleming created him."

James Bond 1992

THE BONDS THAT NEVER WERE

A 30th Anniversary Look at Some of the Film 007s that

Didn't Make It (Including One that Did But Disappeared)

By TOM SOTER

from Video Times, 1992

The images are evocative: an Aston Martin, a martini shaken not stirred, a grim smile, a tuxedoed man saying, "Bond. James Bond." It's all part of a ritual that seems as old as movies themselves. Hard to believe that Dr. No, the first film, appeared in 1962. Bond has survived the death of his creator, Ian Fleming, the departure of Sean Connery, and the igonimy of Roger Moore. He has turned from tongue-in-cheek suspense to tongue-in-cheek cartoon without losing a dollar at the box office. The 007 movies have netted more than $2 billion in ticket sales.

James Bond is forever. Connery, Moore, George Lazenby, David Niven, Timothy Dalton – all have taken the part. But what might have happened if other actors had become Bond? What kind of agents might they have been?

Well, there is a bonda fide, "forgotten Bond": Barry Nelson, who played 007 before the agent was even a gleam in Connery's eye. Never heard of him? You're not alone. Nelson, a popular American TV sitcom star of the 1950s (he appeared in 103 episodes of My Favorite Husband), was cast as the first Bond in a television version of Ian Fleming's initial 007 novel. Casino Royale, shot live in 1954 for CBS's Climax anthology series, was long thought lost, but has recently resurfaced on video.

If you pick up the tape, don't expect any wry double entendres or martinis shaken not stirred. Unlike the suave Connery, TV's Bond ("Jimmy" to his friends) is a stocky American in an oversize tuxedo with a lot to say and not much to do. "We were live and confined to a few sets," recalls Nelson, now 70. "And when you take something like that, which depends primarily on action, you're in terribletrouble." Indeed: the only true Bondian elements are larger-than-life villain Peter Lorre and sultry "Bond Girl" Linda Christian. Yet even she was transformed for Eisenhower-era television. Says Nelson: "Linda and I did kiss – but very politely."

Then there are near-misses, actors considered but rejected for the role:

McGoohan Patrick McGoohan, an obvious choice for the part, claims to have turned it down three times, the first because of a subpar script (others say it was because he thought the character immoral). The New York-born Irishman was well-known on the British stage and TV screen, especially in the long-running spy show Danger Man (1961; 1964-1966). As John Drake, McGoohan questioned his superior's values and was openly skeptical about the stated "necessity" for what he was doing. "You never saw me fire a gun," he says now. And he never dallied with the damsels. "I said to the producers, 'If I start going with a different girl in each episode, what are those kids going to think out there?" McGoohan's Bond would have been a principled spy, who believed that physical prowess wasn't always the answer to tight spots.

McGoohan Patrick McGoohan, an obvious choice for the part, claims to have turned it down three times, the first because of a subpar script (others say it was because he thought the character immoral). The New York-born Irishman was well-known on the British stage and TV screen, especially in the long-running spy show Danger Man (1961; 1964-1966). As John Drake, McGoohan questioned his superior's values and was openly skeptical about the stated "necessity" for what he was doing. "You never saw me fire a gun," he says now. And he never dallied with the damsels. "I said to the producers, 'If I start going with a different girl in each episode, what are those kids going to think out there?" McGoohan's Bond would have been a principled spy, who believed that physical prowess wasn't always the answer to tight spots.

Richard Burton. Talked about for the part in the 1950s when Fleming was trying to mount a Bond film on his own, Burton was powerful, athletic and attractive with a sour wit – seen in such films as The Robe, Look Back in Anger – which would have made him an ironic, almost bitter, Bond. He used this quality to good effect in the anti-espionage flick The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, where the actor played a burned out, disillusioned spy who lacks glamour, gadgets, and legions of willing women. What he does have are brains and compassion – and the latter is shown to be fatal in the spy game.

Sam Neill. Up for the part in 1986, Neill has the intensity of a young Connery, as well as his darkly handsome looks. In My Brilliant Career, Dead Calm , and the TV series Reilly Ace of Spies, Neil displayed an undercurrent of savagery beneath a polite veneer. Tom Mankiewicz, a former 007 screenwriter, could have been talking about Neill when he observed: "Connery carries violence with him.‘ He's got a glint in his eye. So I think an audience's impression when Sean walks in is, 'Uh-oh, look out. Something's going to happen here!"

Brosnan in Remington Steele.Pierce Brosnan, who almost had the part in 1986 but lost out because of contractual difficulties, would probably have carried on in the Roger Moore tradition ("I'm more of a light comedian than Sean," said Moore). Brosnan made his mark in TV's Remington Steele, where the hero was a lightweight man of action, not unlike Moore's Simon Templar in The Saint series of the 1960s.

Brosnan in Remington Steele.Pierce Brosnan, who almost had the part in 1986 but lost out because of contractual difficulties, would probably have carried on in the Roger Moore tradition ("I'm more of a light comedian than Sean," said Moore). Brosnan made his mark in TV's Remington Steele, where the hero was a lightweight man of action, not unlike Moore's Simon Templar in The Saint series of the 1960s.

Adam West. TV's Batman and a 007 candidate in 1968, would have offered Bond as Camp Figure, mock serious and even more comic-booky than Moore.

Burt Reynolds. A contender in 1970, Reynolds would probably have brought a down home light-heartedness to the role – as he did in the Smokey and the Bandit movies – but he can also be tough (see Sharky's Machine, and City Heat, among others).

Mel Gibson. He might have radically shaken up the series. His violence is tempered by very little humor and his 007 would have been more Mad Max than Ian Fleming, harder-edged and more brutal.

Jimmy Stewart. The most unusual Bond would have been Stewart, who was considered for the role in 1958. The actor's many movies include Alfred Hitchcock's 1956 The Man Who Knew Too Much, in which an innocent man is involved in a nefarious spy scheme. A few years later, Stewart was turned down for the led in North by Northwest, another Hitchcock that is a precursor to the Bonds: the hero is a womanizing, faintly ammoral advertising executive with a dry wit. Stewart was never cast as 007, and it's hard to imagine what audiences would have made of a drawling, silver-haired Bond.

James Bond 1993

THE CONNERY COLLECTION VOL. II

THE CONNERY COLLECTION VOL. II

1993 comp. Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967), Diamonds Are Forever (1971); Sean Connery, Claudine Auger, Donald Pleasence, Jill St. John; dir. Terence Young, Lewis Gilbert, Guy Hamilton. (PG) 364 min. LBX. Digital ‘ stereo. Trailers included. CLV, 8 sides. MGM/UA

James Bond producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman love gadgets. And they must love explosions almost as much, considering the number of them that turn up in the three Bond films included in The Connery Collection, Vol. II: underwater, in the air, or inside a volcano, you name it and Broccoli and Saltzman can blow it up. But luckily, there's more to super-spy 007 than dynamite, or else there would be no interest in this boxed set, the umpteenth repackaging of the Bonds for the laser market.

The best Bonds define classy adventure, and the best Bonds all have Sean Connery. The actor is the highlight of the trio of tales featured here, which demonstrate the highs and lows of the series. The world-menacing action, beautiful women, and exotic locales are all plentiful, but so are trends that helped destroy the series' integrity in the Roger Moore years: excessive gadgetry (Thunderball), too much travelogue (You Only Live Twice), and too many jokes (Diamonds Are Forever). For all that, Twice has great pacing, while Diamonds has great wit, accentuated by Connery's deliciously deadpan delivery (Buxom Girl: "My name is Plenty. Plenty O'Toole." Bond: "Named after your father, perhaps?").

Besides trailers and chapter stops, The Connery Collection offers little that can't be had elsewhere and adds a few major gaffes, as well. The brief background literature features inaccurate running times, an inflated budget for Thunderball, and the laughable assertion that Bond's creator, Ian Fleming – dead two years when Thunderball was made – "teamed with Broccoli and Saltzman to produce a new version of the screenplay." Indeed. If the author of such misinformation had worked for 007's nemesis SPECTRE, he would have already had a visit from The Execution Branch. VIDEO, 1993

James Bond 1999

THE WORLD IS NOT ENOUGH

By TOM SOTER

from MOVIE TIMES, 1999

In James Bond movies, as in real estate, the catchphrase could be “location, location, and location.” While many moviegoers have flocked to the 007 thrillers for the gadgets and girls, a prime appeal has also been the franchise’s exotic foreign locales. A travelogue with a kick, the globe-hopping series has found its villains on the beachfronts of the Bahamas (Thunderball), skiing down the snow-peaked Swiss Alps (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service), hiding among the pyramids of Egypt (The Spy Who Loved Me), and lurking in the Turkish flea markets of Istanbul (From Russia With Love).

For The World Is Not Enough, the new Bond opening November 19, one location was certainly not enough: Pierce Brosnan’s third 007 outing finds the superspy jetting from London to Turkey and from Spain to the French Alps in a battle royale to save the world’s oil supply from destruction.

The tricky location work involved staging a high-speed motor boat chase on the busy Thames river in London. The sequence found the actors firing off machine-guns outside the Houses of Parliament, while the crew set off dynamite near the financial district and at the Victoria Docklands, next to the city’s airport. Besides creating explosions that had maximum effect with minimum impact, the production team also had to work closely with air traffic controllers so that the shooting did not disrupt any aircraft overhead. Noting that there were 25 different locations within this one episode alone, producer Michael Wilson wryly observed: “This is something no one else has tried before. And when I see the logistics involved, I understand why.”

The crew also flew to the town of Chamonix in the French Alps for an aerial ski chase that had to cope with the serious possibility of avalanches. In addition, there were other problems that made some feel as though they were in the military: “It’s pretty inaccessible, especially when it snows,” said second unit director Vic Armstrong. “It’s like moving an army.”

Nonetheless, for 007’s audiences, those larger-than-life miracles are par for the course. “You come to each Bond film looking to make it bigger and better,” noted miniature effects supervisor John Richardson. “That’s the challenge.”

James Bond 2

for what it matters

BOND IS BACK

By TOM SOTER

from THE COLUMBIA DAILY SPECTATOR

July 28, 1977

Bond (Roger Moore) vs Jaws (Richard Kiel)

The Spy who Loved Me is the tenth james Bond movie (or eleventh' if you count Casino Royale) . which means that things should, be getting' either tired or different by now. They are. Spy is more a lifeless remembrance of Bond's past than anything else. There is the villain in the underwater hideout (Dr. No); the brutal fight on the speeding train (From Russia, With Love); the car that can do anything (Goldfinger); the hungry sharks and threatening scuba divers (Thunderball); the impossible ski chase (On Her Majesty's Secret Service); and the kidnapping of American and Russian crafts which could lead to international holocaust (You Only Live Twice).

It is this last reference that has predominance in Spy. The mad genius who threatens the world with destruction is a staple in Bond thrillers in general, and in You Only Live Twice in particular. The difference here is that the bad guy (Curt Jurgens) is about as menacing as. a nasty boys' school dean and merely adds to the, weightlessness that besets. not only the villains, but the heroes and storyline as well.

Roger Moore, for instance, is a dull Bond. He lacks his predecessor Sean Connery's ability to laugh at himself and us for taking, things too seriously. Moore is merely impeccable and: about as interesting as the department store dummy he resembles.

Qutside of the casting, however, die very fact that 007 has become invincible prompts only yawns. In Goldfinger, the secret agent's helplessness in the face of the super-strong Oddjob made his predicament more suspenseful and his triumph all the more satisfying. Here, there is Jaws, a perverse, superhuman thug who kills people by opening their necks with his metal teeth, and is apparently' indestructible (he wrestles with a shark & wins). Even so, he. is not very menacing because we know that Bond can triumph over anyone.

The Spy Who Loved Me and most of the recent 007 films lack the excitement of the earlier Bonds because they have lost the necessary human element. We can no longer identify with the secret agent because he is now too sure of himself-too much of a superman. In addition, his sadism is now rampant (he kills an unarmed foe by, shooting him in the groin) and his frequent puns ("When in Egypt one should delve deeply into its beauties") make him seem more insecure and tasteless than clever.

In short, there is nothing to recommend this movie, which recalls the '60's Bonds without actually reliving them. It is a hollow, composite reincarnation-a fact made sadder when one thinks of the great times that 007 has given us in the past.

But the most apppropriate comment· comes from the' film itsellf- Bond approaches a hawk-nosed man and gives the standard "My Name is Bond. James Bond." The man replies "What of it?"

James Bond

An Interview With James Bond

Screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz

By TOM SOTER

from the NEW YORK VOICE

August 22, 1987

"The Living Daylights" introduces a new James Bond, in the person of dashing, intense Timothy Dalton. He's as much a success with his serious sty[e, as his immediate predecessor, Roger Moore, was with his flip one. What did the man who wrote Moore's first Bond epic, "Live and Let Die," think of his leading man? In the following interview, Mankiewicz provides some answers to that and other questions. Mankiewicz co-wrote ''Diamonds Are Forever" and "The Man with the Golden Gun, " and wrote "Live and Let Die." His non-Bond efforts include "Superman II" and "Superman III, " and the Bill Cosby film "Mother, Jugs and Speed. " He created and supervised the TV series "Hart to Hart."

New Bond on the beat: Roger Moore (seated) with (left to right) producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman on location for "Live and Let Die."

New Bond on the beat: Roger Moore (seated) with (left to right) producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman on location for "Live and Let Die."

Q: You worked on three Bond pictures as screenwriter with two different Bonds. Can you compare your relationships with Sean Connery and Roger Moore?

A: I had a terrific relationship with both. With Sean, I was really surprised because when I first met him in Las Vegas on the day he arrived, he had read the script and made notes on it. I was surprised by how much homework he had done. He had gone through it very carefully and the thing that was surprising to me was that most of the notes he had were for other parts. For instance, he would say, "Couldn't she say something better than this to that guy?" Most of the time it had nothing to do with him.

I never really had a meeting with Roger like that. Roger's contributions are more in the dialogue area. He's very quick and his contributions tend to happen on the spur of the moment. For instance, Roger had an ad-lib in "Live and Let Die" where the girl says, "I guess as an agent I'm a total bust." And he said, "I'm sure we'll find some way to lick you into shape." Which I loved. Roger is terrific to work with.

Q: How was it writing for the two actors? Their styles are very different.

A: I think you write to their strengths. Roger's is comedy. For instance, Roger Moore walking into the Filet of Soul, a Black bar in Harlem in his very British Chesterfield coat. You get great comedy out of it because he looks like a twit. On the other side, Sean walking into the Filetof Soul – Sean carries violence with him. He looks like a bastard; he's got a glint in his eye. So I think the audience's impression as Sean walks in is, "Uh-oh, look out. Something's going to happen here." And one does think that if Roger starts to do exactly the same sort of things that Sean did, the audience is going to resent that.' So it's part and parcel of trying to write to their strengths.

Q: Connery reportedly enjoyed working on "'Diamonds Are Forever." Did they try and get him back for the next one, "Live and Let Die"?

Sean Connery and Lana Wood in "Diamonds Are Forever."

A: At the last minute they made another attempt to get Sean back. I remember having dinner with him just before "Live and Let Die" began shooting and he said, "How's the script?" And I said, "It's just terrific, Sean. It really would be a lot of fun." And we didn't have a Bond then and I said, "Would you like to read it?" And he refused. I think that's because he didn't want to get tempted again like he was with "Diamonds." He said to me, "Boyo, all they can offer me is money." And that's what he didn't need. And I brought up the quesiton of his "obligation" to his public to play Bond. He said to me, "Six pictures over ten years; How much of an obligation have I got? When does it run out? Should we put a limit on it, say I5 pictures over 30 years? One more this year and then is my obligation over?" He said the only two things he ever wanted in his life were to own a golf course and a bank. And he had both.

Q: I understand there were some casting problems in "Live and Let Die"?

A: When we started writing "Live and Let Die," one of the things that I wanted very much, and the director, Guy Hamilton, wanted very much, was for, the heroine, Solitaire, to be played be a Black woman. United Artists, the distributor, was'very scared of it. I thought having, a Black heroine would ease the basic problem of the film, a white man beating up Blacks. But when it carne time to do it, U.A, was quite frightened of it for legitimate reasons from their point of view. The picture was going to be very expensive and they wondered, outside of cities like New York and London. How well that would go over with a new Bond. They'd had the experience of "On Her Majesty's Secret Service," which had done poorly. But we didn't know they were going th renege on this idea. And the first person who was brought up in casting sessions for the Solitaire part was Catherine Deneuve. And I said, "Well, she's not terribly Black." Sort of the antithesis of it.

Q: What about the casting of Moore?

A: Cubby and Guy went over to the Goldwyn lot to meet an actor named Burt Reynolds, who was doing a series called "Dan August."And Guy thought he was charming as hell. And as a matter of fact, the choice wlls between Burt Reynolds and Roger Moore. Roger Moore. He had just done "Deliverance" and I think the biggest problem with him would have been getting him to sign for three pictures. And Cubby was the one who said, "I don't care what happens. Bond must be British." So Reynolds was out.

Q: What was it like working with the producers Albert R. (Cubby) Broccoli and Harry Saltzman?

A: Harry is so mercurial. He gets these brainstorms. He had an obsession that Bond would wake up in bed in "Live and Let Die" and there would be a crocodile next to him. And I said, "Harry, first of all, they've got such little legs. How does he get up there? Harry said, "Somebody put him there." I said: "Who?" He said. "I don't know – but I know that Bond gets up and there's a crocodile right next to him." "Why doesn't the crocodile eat Bond?' "He's noi hungry." He really wanted it and we didn't get it in.

Now Cubby is more the conscience.of the audience. He wants to make sure everyone understands everything. I used to use the example-that never happened – that you could say to the two of them, "Bond falls off the boat and as he's sinking underwater, he meets an octopus. But it has nine arms.'' Harry would say, "And he's bright red and he's on roller skates and he blows up." And Cubby would say, "I still don't understand what's funny about the nine arms." You'd say, "But, Cubby, octopusses usually have eight arms." And he'd say, "1 know that. But do you think everyone in the audience is going to get that?'"

Q: Do you know why they split up?

Christopher Lee and Maude Adams in "The Man with the Golden Gun."

A: There were all kinds of reasons. Basically, they had totally different lifestyles. Cubby's life is those films. He loves working on them, Harry is just a natural wheeler-dealer. He has such an active and unfocused mind that he loves to be into 12 things at a time. There are people like that who just need that kind of action. There's a story about Harry. He wanted to have a sequence in a salt mine in "You Only Live Twice" and he said, "We've got to have one in a salt mine." He took an art director and a bus and he went all over Japan before finding out two weeks later that there are no salt mines in Japan. But that wouldn't stop Harry. He would say, "Nonsense. The just haven't found any yet."

James Bond Girls

TOMORROW NEVER DIES

BOND'S WOMEN

By TOM SOTER

from MOVIE TIMES, 1999

It may not be very PC anymore, but the phrase “Bond Girl” has become part of the filmgoer’s lexicon. And when Tomorrow Never Dies, the latest James Bond epic, opens on December 19, karate-chopping Michelle Yeoh, veteran of many Chinese action movies with Asian superstar Jackie Chan, will join a list of Bonded beauties that goes all the way back to 1962.

007 Bond Girls: Then & Now: Fresh off her fame from playing Cathy Gale on the 1960s British show The Avengers, Blackman remains one of the most memorable, and oldest, of the Bond girls around. Although she mostly kept to theater work in London since her stint as a Bond girl, American audiences saw her as Penny Husbands-Bosworth in Bridget Jones' Diary (2001).

007 Bond Girls: Then & Now: Fresh off her fame from playing Cathy Gale on the 1960s British show The Avengers, Blackman remains one of the most memorable, and oldest, of the Bond girls around. Although she mostly kept to theater work in London since her stint as a Bond girl, American audiences saw her as Penny Husbands-Bosworth in Bridget Jones' Diary (2001).

That was the year when Doctor No, the first Bond adventure, introduced the series’ classic heroine: Honey Rider, played by statuesque and exotic Ursula Andress. Since then, there have been nearly two dozen Bond Girls, whose type has changed with the changing times. The most widely remembered is probably Shirley Eaton, who graced magazine covers and posters as the “golden girl” in Goldfinger (1964), killed by having her body painted gold.

But others have left their mark, as well, including pop singer Grace Jones (A View to a Kill, 1985), TV mini-series bad girl Barbara Carrera (Never Say Never Again, 1983), Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman heroine Jane Seymour (Live and Let Die, 1973), Shakespearean-trained Diana Rigg (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, 1969), and the first proto-feminist Bond babe, Barbara Bach (The Spy Who Loved Me , 1977). Bach, the wife of Beatle Ringo Starr, didn’t think much of Agent 007, however, saying the character was “a male chauvinist pig who uses girls to shield him against bullets.”

Karate expert Yeoh has other ideas. She hopes to make a mark – both literally and figuratively – as Chinese spy Lin Pao, who is a different kind of Bonded heroine. Says Yeoh: “I’m more of a ‘90s woman. I’m smart but also very physical.”

James Bond: Barry Nelson

THE FILM BOND IS 30 NEXT YEAR

THE FILM BOND IS 30 NEXT YEAR

By TOM SOTER from VIDEO, 1991 Before James Bond was even a gleam in Sean Connery's eye, there was Barry Nelson, the original Agent 007. Never heard of him? You're not alone. Nelson, a popular TV sitcom star of the 1950s (he appeared in 103 episodes of My Favorite Husband), was cast as the first Bond in a television version of Ian Fleming's initial 007 novel. Casino Royale, shot live in 1954 for CBS's Climax anthology series, was long thought lost, but has resurfaced on video. If you pick up the tape, however, don't expect any wry double entendres or martinis shaken not stirred. Unlike the suave Connery, TV's Bond ("Jimmy" to his friends) is a stocky American in an oversize tuxedo with a lot to say and not much to do. "We were live and confined to a few sets," recalls Nelson, now 70. "And when you take something like that, which depends primarily on action, you're in terrible trouble." Indeed: the only true Bondian elements are larger-than-life villain Peter Lorre and sultry "Bond Girl" Linda Christian. Yet even she was transformed for Eisenhower-era television. Says Nelson: "Linda and I did kiss – but very politely."

John Barry

By TOM SOTER

from STARLOG, February 1994

John Barry is nothing if not eclectic. He is, after all, the man who could write a sweeping, sentimental theme for Out of Africa and then turn around and compose the pounding, action tunes for James Bond in The Living Daylights. He is also the man who could write the beautiful choral interludes of The Lion in Winter – and then later pen the synthesizer-based fright music of Jagged Edge.

“I think he occupies a quite unique place in the cinema of today,” notes director Bryan Forbes, who worked with Barry on six movies. “He doesn't swamp you with the of 400 violins, and the idea of using a heavenly choir would make his somewhat cherubic locks turn gray. He makes music for films, and it is something beyond good music for films. It is music that lives outside the celluoid wrapping, music that people buy and listen to for its own sake.” Indeed. Perhaps no other movie compose has created so many catchy, wordless tunes that are so different from each other. Think of Elsa the Lioness and you think of Born Free. Think of Tilly Masterson painted gold and you think of Goldfinger. Or think of John Dunbar on the plains, or Isak Dinensen in the air, and you think of Dances With Wolves and Out of Africa. And all the time, you are thinking of John Barry.

"His music is meant to be heard, not seen," wrote critic Harvey Siders, who points to Barry's "inventiveness for orchestral colors and infectious rhythms, his gift for melody, majestically sweeping or deceptively simple; his ability to paint indelible pictures, conjure up images that run a gamut from the hip to the hippie; and above all, his complete mastery of the orchestra." But for a man who has done so much, Barry in person is remarkably low-key. His voice is deeper than you would expect, still thick with his native Yorkshire accent even after years of exposure in America. His latest score is for Indecent Proposal, in which multi-millionaire Robert Redford buys Woody Harelson's wife, Demi Moore, for a one-night stand. "It was one of my most difficult scores," Barry admits. "The problem was the characters: the balance of how you play them off together, and come out at the end of the movie, feeling good about all of them, writing the music for that, [it was hard] to keep the balance - because if you pushed Redford too much one way, then you're tipping the scale the wrong way. It was like walking on eggshells, on a tightrope. It was unbelievable, keeping that emotional balance of the melodies in control. How does one interplay all those moments? That is the simplest thing I've ever written. But believe me, it was a nightmare getting there."

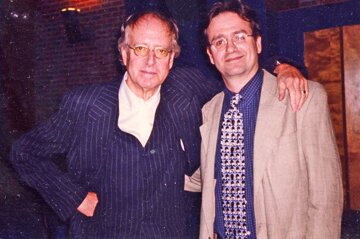

John Barry (left) with Tom Soter.

Composer Nightmares Nightmares are part of a film composer's life – after all, it is music that must work in conjunction with someone else's images, usually timed very precisely – but Barry had always wanted to embrace those images. In fact, the combination comes naturally when you consider his upbringing: the youngest of three siblings, he had a father running a chain of eight cinemas in northern England and a mother who loved to play the piano. By 1942, when he was nine, Barry was studying music. "I took piano lessons, and I started studying harmony, counterpoint, and composition at 12." At 16, after working as a projectionist, he began playing trumpet and then studid with the master of music at York Music. "My first love was classical music," he recalls, adding that he still listens to Stravinsky, Mahler, and Mozart. Although classically trained, he admits he was more interested in film composing than concert conducting, so with an eye towards that, he took a correspondence course in composition, orchestration, and harmony. In the Army, he played trumpet in a band, and afterwards, he formed his own rock-jazz group called the John Barry Seven.

"I didn't love [pop] music, I wasn't passionate about it. But I did want to be a professional musician," he explains. "So we literally listened to all that was coming out of America at that time, whether it was Bill Haley or Freddy Bell and the Bellboys and all that stuff, and the first concerts we did, we just copied all their stuff and did it. Then I started to write things in that vein myself. Within three or four months of forming this group, we were hired professionally and opened at the Palace Theatre at Blackpool with Tommy Steele. So, the plan worked."  In more ways than one. Barry began composing ppp tunes by the truckload, and one of them, "What Do You Want?" sung by Adam Faith, entered the BBC radio hit parade three weeks after its release in 1959 to become a No. 1 tune, selling 50,000 copies in a day. By the end of 1960, it had become the year's biggest-selling record.

In more ways than one. Barry began composing ppp tunes by the truckload, and one of them, "What Do You Want?" sung by Adam Faith, entered the BBC radio hit parade three weeks after its release in 1959 to become a No. 1 tune, selling 50,000 copies in a day. By the end of 1960, it had become the year's biggest-selling record.

Yet Barry pined for the movies and would take anything that brought them closer. In 1959, in an effort to learn more about scoring, he took the job of musical director at EMI Records. "In the early days I would write anything," he says. "I was doing commercials for toilet paper. At that point in my career, you were not in a position to be picking and choosing. You were getting the experience, you were getting a pay check, you were starting a career."

Musical Emotions Movie work finally came with Beat Girl, a teenage exploiitatin movie featuring Adam faith. Barry knew Faith and the producers knew the JB7 as a hit instrumental rock group, so the composer got his chance. The music was so impressive, in fact, that EMI took the unusual step of releasing it as an album. Barry did in Beat Girl what he would do in later pictures: compose music that was noteworthy but unobtrusive. The trademark Barry score would contain haunting tunes, menacing music, and evocative melodies that created feelings, enhanced actions, and set mood and texture. "I cannot write without having an emotion [for the characters]. It's mot my nature,"' he observes. "There has to be an emotion."

On his Academy Award-winning Dances With Wolves, for instance, he read the script and immediately thought of a melody for the iconoclastic hero John Dunbar. "You have to get involved with Dunbar and this guy after the Civil War, this merchant man getting up, saddling his horse and riding out there. He wanted to see what it was. And that's why that theme is almost like a last post, you know, it's like a death wish. It has a lyrical quality, a tentative quality,and that was the start. That's the way I felt. I sat down and wrote that once I had read the script. I didn't even see the movie. I wrote that single thought and then everything grew from that. I wasn't trying to be Aaron Copland, which I think would have been totally wrong. That's where all the other western scores came from."

It's a technique that harks back to 1962, when Barry received a frantic phone call from Noel Rodgers, head of music at United Artists. Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, the producers of Dr. No, the first James Bond film, were unhappy with the work of the film's composer, Monty Norman. They needed some catchy instrumental music for Bond, so Barry, without seeing the movie or knowing much bout 007, whipped up "The James Bond Theme" by reworking some of Beat Girl's chords ("It's that same accent guitar riff," he notes). The tune became a hit, on screen and off, reaching No. 13 on the British music charts. More significantly, it led to Barry's association with the superspy James Bond, his cinematic alter ego. He scored From Russia With Love masterully, but it was on Goldfinger that everything clicked.

"The star came together on the Bond thing," he notes. "From everybody's point of view. I mean, I love From Rusia With Love, but Goldfinger was it." It was the first Bond for which he was asked to co-write the title song, the quintessential Bond theme (ironically, although it became a million-seller, co-producer Saltzman hated the tune and wanted to remove it). Barry collaborated with Leslie Bricuse and Anthony Newley on the lyrics. "I went to Tony because we had the same divorce lawyer," the composer says. "Tony said, 'Well, what the hell is this about? So I said, 'It's Mack the Knife. It's a song about a villain. So, that seemed to be a good opening line. Then, they wrote the lyrics."

Collaboration soon became the key to Barry's approach – not necessarily between people but between image and idea, music and action. He admits to looking at the story and characters first, working out initial themes on the piano. He can then take three to four weeks to write a score (although key parts of Thunderball were composed in two days, and the entire score for The Man with the Golden Gun took two weeks). "Whether it's a horror movie, an action movie, a love story, a historic piece, it can be any one of those. It's how good the writing is, essentially. How good that script hits you, and then who is the director. Then you go through the whole thing of who's doing it, who's going to be casting, so you come out at the end and you make those choices. And as I say sometimes they could be terribly right and sometimes they could be disastrous."

He remembers 1986's Howard the Duck with a shudder and a chuckle. "I had just finished Out of Africa with the same company, which wound up a hugely successful movie; it won all the Academy Awards. I got this mad phone call [from the film company, Universal Pictures] and they said, 'It;s George Lucas's movie,' and I thought, ''Well, a cartoon death wizard, a ridiculous thing; it just might be fantastic.' So, I said, 'OK.'" Barry scored sequences without seeing the special effects, recalling that "I went blindly, with confidence, and I thought that [Lucas] was going to be taking care of all that. That never worked out. I still don't know what happened. It was such an unbelievable disaster. And I never met George Lucas."

Film Collaborations Barry believes the director is key to a proper marriage of picture and score. He has worked with some of the best: John Schlesinger, Arthur Penn, Nicholas Roeg, George Cukor, Richard Attenborough, and Sydney Pollack, and admits to being most impressed by Schlesinger's musical knowledge. He notes that directors often have preconceived ideas about music -- "their choices are too obvious" -- which the composer must change with a fresh concept. "Good directors listen," he notes. Sometimes they don't, however, and that can lead to clashes, as it did when he left the Barbra Streisand movie, Prince of Tides. "Sometimes you just don't get on with somebody," he says. "It's a collaborative system. You listen, if the director starts thinking that they can actually compose music, then I pass."

Sometimes the directors know about music, which helps. "When I started working on Indecent Proposal, the initial things I wrote were wrong. Adrian [Lyne, the director] was very observant in saying, 'If this was Mastrianni and John Barrow, these themes would be terrific, but they're too European and they're too mature.' So I had to de-Europeanize myself and demature myself, if there's such a word, and come down to an easier form of American romanticism. That's why I like working with Adrian, because he was at least able to articulate what was wrong." By the late '60s, Barry had begun branching out, becoming bored with what he was calling the "Million-Dollar Mickey Mouse Music" of the Bonds.

In the '70s, he was at work on a stage musical, Billy (based on the film Billy Liar), a film musical of Alice in Wonderland, an album of original compositions, Americans, beautiful historical drama scores (Robin and Marian, The Last Valley, Mary Queen of Scots), and TV-movies (Eleanor and Franklin, The Corn is Green).  He began alternating on 007 epics – skipping Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me, and For Your Eyes Only – and his distinctive melodic action music was greatly missed, replaced by the hollow sounds of George Martin in LALD or the disco beats of Bill Conti in FYEO.

He began alternating on 007 epics – skipping Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me, and For Your Eyes Only – and his distinctive melodic action music was greatly missed, replaced by the hollow sounds of George Martin in LALD or the disco beats of Bill Conti in FYEO.

"I always treated the Bonds very seriously," he observes. "I never treated them fliply. Even those action sequences were -what shall I say – relatively clean compared with the mixes that go on today. I just don't find they have any dramatic thrust other than pure energy and noise. There didn't seem to be any linear motif. They don't stretch it dramatically. It's very unstructured. It's just not good dramatic writing." There are no more Bonds in Barry's future, however -- even though his presence was felt in Licence to Kill's Michael Kamen score ("They ripped off the opening bars of Goldfinger," he laughs). "If they make the [next] movie fresh, that would be something, but the way they're going I don't know, I can't believe that it's going to be a sparkling new concept."

Past Scores He himself stays fresh by keeping true to his ideas of good music, irrespective of the ideas associated with a particular genre. His fantasy films include Somewhere in Time and Peggy Sue Got Married, and he has dabbled in sci-fi scoring, first with You Only Live Twice, then with The Black Hole (the first digitally recorded motion picture), Starcrash (the score won a special prize at the Festival du Cinema Fantastique in France), and Moonraker. However, instead of using the expected sounds of scifi – synthesizers and electronic instruments – he went for "kind of strange, spacey, harmonic progressions. Before I think of melodies or anything, I think of harmonic progressions that have a strange, almost transparent, translucent spacey feeling about them, then I go and stretch things over that."

He rarely looks back at the past. He is dismissive about plans to release his older work on CD, as well as the recently released rarities from Thunderball included on The 30th Anniversary James Bond Collection. "I don't want to be any part of it," he says brusquely. "It's past. It's done. It's all over. Move on. If some fan or fanatic wants to dig through all those files that's fine. That's their pleasure."

Yet he does think fondly of his scores. "I bleed on every movie I do and I'm very faithful to every movie I do, I'm a ham in that way. Like Raise the Titanic. I worked my butt off, but I am the composer. I'm not the overseer of every other thing. I like what I've done." So much so that he has dipped into his musical history for a new CD collection, Moviola, which features some of his greatest hits (as well as the tune "Moviola," the original theme for Prince of Tides). "I went back over the whole repertoire, and thought, 'Well, I'd love to do almost a lyrical album.' I've done enough work over this period of time to put together, I think, a really terrific lyrical album."

Connery in Diamonds Are Forever.

Connery in Diamonds Are Forever.

With the past intruding in the present, Barry is still searching for something new, still yearning for the eclectic and the unusual. "I would very much like to do a jazz album – a moody jazz album. I love orchestral settings, and I am in initial talks at the moment with the people at Sony [because] they have some terrific jazz artists. I would love to put together a group of their people, maybe ten, that are really the finest people, and do a real free form kind of jazz-inspired album, if you like. It's my roots. From my mid-teens onward, I became a huge jazz fan. I would just like to put it into slightly more sophisticated harmonic setting. I could have a lot of fun doing that."

Influential Notes Married, with three grown children, the composer is looking to the future, although he almost never had one when a healthfood beverage caused a ruptured esophagus in 1988. He nearly died, but after four major operations in 14 months, he recovered. He now jokes that every artist in his 50s should take an enforced sabbatical -- just not the way he did. Barry's ideal work situation is to be alone at his home in Oyster Bay, New York, creating tunes in his office lined with photographs and autographed scores of Prokofiev, Bartok, Mahler, and other composers.

"I love the isolation," he says. "I have a beautiful studio that overlooks the lawn right down into the sea. Total peace. I can work under other conditions -- the week before last I finished a movie up in a hotel room at the Regent Beverly Wilshire -- but the ideal thing is real concentration. I don't have any social life when I start to work, it's just that kind of intensity I like: to write, to go for a walk on the beach, come back, reflect on what you've written, and you've got 24 hours in the day that are totally yours, to deal with as you wish. You think about it. You're getting it in your mind mentally.

"I have millions of influences," he adds. "But when I sit down and write, I hope I'm my own best influence. I hope, as a dramatist, I sit down in the loneliness of my room and my house and my beach and my dogs and my cats and my wife – I should put my wife first – but that's the presence where you start. You figure out your own individual way of how am I going to do this? What's this going to be? In terms of my appreciation of other - composers, I could talk for three hours on that, but when you're actually doing the job at hand, it's your own self. You have to come down to your own self and how you figure it out, how you're going to do it. You go through all this process, mental process and then you sit down and you do it. It's what you're not going to do that matters, it's what you throw out. And then you're left with the bare bone. You work with the bare bone."

Roald Dahl

from STARLOG August 1991

Roald Dahl hated screenwriting. "If you've got enough money to live comfortably, there’s no reason in the world to do a screenplay. Harry Curtis once said that the only reason anybody ever does a screenplay is because you’re paid so much money and because you're hungry. It's an awful job.” And yet, before he died on November 23, 1990, Dahl had written some of the genre's most notable – or at least lucrative –screen works. In 1959, he adapted his short story "Lamb to the Slaughter" for Alfred Hitchcock Presents; in 1967 and 1968, he authored the screen versions of two Ian Fleming fantasies: the James Bond caper You Only Live Twice and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, a children's book about a flying car. In 1971, he scripted the film version of his bestselling Charlie and the Chacolate Factory. And just months before his death, he saw his story The Witches adapted by writer Allan Scott and director Nicolas Roeg into a critically acclaimed film, which he reportedly disliked. Roeg noted, however: "Roald is a great, great storyteller. I don't know anyone comparable to him." The Man’s Life

Roald Dahl hated screenwriting. "If you've got enough money to live comfortably, there’s no reason in the world to do a screenplay. Harry Curtis once said that the only reason anybody ever does a screenplay is because you’re paid so much money and because you're hungry. It's an awful job.” And yet, before he died on November 23, 1990, Dahl had written some of the genre's most notable – or at least lucrative –screen works. In 1959, he adapted his short story "Lamb to the Slaughter" for Alfred Hitchcock Presents; in 1967 and 1968, he authored the screen versions of two Ian Fleming fantasies: the James Bond caper You Only Live Twice and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, a children's book about a flying car. In 1971, he scripted the film version of his bestselling Charlie and the Chacolate Factory. And just months before his death, he saw his story The Witches adapted by writer Allan Scott and director Nicolas Roeg into a critically acclaimed film, which he reportedly disliked. Roeg noted, however: "Roald is a great, great storyteller. I don't know anyone comparable to him." The Man’s Life  Roald Dahl: "a great, great storyteller."

Roald Dahl: "a great, great storyteller."

Dahl was born 75 years ago in Wales, the son of Norwegian parents. A Royal Air Force fighter pilot during World War II, he was seriously wounded while flying over the Libyan desert. The novelist C.S.Forester (whose literary creation Admiral Horatio Hornblower was later the model for Star Trek's Captain James T. Kirk) heard the tale and suggested Dahl write it up as a story for the Saturday Evening Post. The success of that led to a career in writing: three novels, nine books of short stories, 19 children’s books and numerous screenplays and TV series.

Directed by Hitchcock for his TV show, Dahl's adaptation of "Lamb to the Slaughter" — in which a wife (Barbara Bel Geddes) murders her husband with a leg of' lamb and destroys the evidence by cooking it and serving it to the investigating policemen – is typical of his macabre sense of humor. It also became one of the series' most famous installments. In 1961, Dahl hosted a Twilight Zone clone called Way Out, and in the early '70s, his fantasy tales were dramatized by others on Roald Dahl's Tales of the Unexpected. Through it all, the writer led a rocky life that left him slightly bitter.

Married to actress Patricia (The Day the Earth Stood Still) Neil in 1953, he nursed her through a series of debilitating strokes in the mid-1960s (their story was the subject of a TV-movie starring Dirk Bogarde as Dahl). The two divorced in 1983. Dahl, who had a son and three daughters by Neal, then married Felicity Ann Crosland.

He became involved in screenwriting almost by accident. In the 1960s, he "wrote an original film script for David [Picker], the head of United Artists at that time, [scheduled to star] Jackie Cooper and [be] directed by an unknown director, Robert Altman," he recalled. "I was writing stories and minding my own business when Altman and Cooper flew out from Los Angeles with this little plot and begged me to do it. In the end-to get rid of them, because they were drunk all the time-I did it. Altman said, 'When you write it, the only condition is that I direct it.' So, I wrote it. United Artists loved it and offered me $150,000 for the first draft, but they wouldn't have this unknown director Altman.

"They bought it and cast Gregory Peck," Dahl added. "[It was] a very expensive film. They all went to Switzerland, shot about 200 feet of film in 10 weeks and lost a fortune because they had a bad director. So, that was cancelled, never made. It had a temporary title, like The Bells of Hell Go Ding-a-Ling-a-Ling. It's still on the shelf.

"The important thing about that little story is that Picker saw this screenplay, which had been made up from nothing. At the time, he was talking to [Bond movie producers] Albert R. ('Cubby') Broccoli and [Harry] Saltzman about how to do You Only Live Twice. They thought of me and I got a call from Broccoli: 'Would you do a Bond script?' I said yes and went up to see them. There were Broccoli and Saltzman, and they said, 'You know, it will have to be completely invented. You can use the Japanese scenes and the names of the characters, but we need an entirely new plot.' So, I said, 'Well, all right.' They picked up the phone, called Swifty Lazar, my agent in California, and closed the deal, and I went away and started writing it. That’s how I got the job. David Picker was obviously impressed by the [Bells] screenplay.”

Sean Connery as 007 in Dahl's You Only Live Twice: "Fleming's worst book."

The Novelist’s Plot