Magazines 2000-2009

A DIFFERENT DECADE

A DIFFERENT DECADE

This was the decade that began with a bang for me with the publication of my second book and ended with sadness: the deaths of my childhood idol Patrick McGoohan and, more significantly, of my father, George. My dad had been a great influence in and a great supporter of my writing and career (indeed, in his last months, he was still critiquing my work, both positively and negatively but always constructively. For a more complete look at my dad and me, see the section "Family Matters," on the navigation bar to the left.) I continued to work full-time at Habitat, continued to freelance (I met childhood hero Fess "Daniel Boone" Parker, although I was unable to place a story I had hoped to do about him) and conducted a phone interview with the charming Avengers star Patrick Macnee. As the decade wore on, I freelanced less, and spent more time teaching and performing improv. I became a vegetarian and lost 30 pounds – and then became a "meatatarian" (and "sweetsatarian") and gained perhaps too much of it back. And I started this (and the Sunday Night Improv) web sites, which are taking up way too much time but are a fun exercise in "Does anyone care about me?" narcissism. Thanks for your interest, whoever you are.

Daniel Boone

From DANIEL BOONE TV SERIES WEBSITE, 2008

002 Tekawitha McLeod (#7402)

Original Air Date: 10-01-64

Written by Paul King

Directed by Thomas Carr

Produced by Vincent M. Fennelly

Fess Parker ............. Daniel

Albert Salmi ............. Yadkin

Ed Ames ............. Mingo

Patricia Blair ............. Rebecca

Veronica Cartwright ............. Jemima

Darby Hinton ............. Israel

Dallas McKennon ............. Cincinnatus

Lynn Loring ............. Tekawitha

Edna Skinner ............. Sadie Clayburn

Chris Alcaide ............. Flathead Joseph

Robert Foulke ............. Sledge Clayburn

David Cadiente ............. Telequah

Donald O'Rourke ............. Timmy Kincaid

and Hannibal, the Goose

By TOM SOTER

The second episode produced, “Tekawitha McLeod” is an engrossing story of family ties and also a parable about race relations that is summed up best by Cherokee runaway Tekawitha’s observation: “The color of my skin cannot change what is in my heart.”

The story is relatively simple, but like many DANIEL BOONE episodes holds deeper meanings. An Indian half-breed kidnaps Tekawitha, daughter of the chief of the Cherokee. She is offered to Boone, and when he learns that she is white, trades her for a jug of rum and some gunpowder and vows to return her to her “people” – her white family. Later, it turns out that he knew her mother, who was actually an early, pre-Rebecca sweetheart, adding a personal stake in his fulfilling his vow. When the Cherokee learn that Tekawitha is in Boonesborough, they threaten to attack the fort unless the princess is returned to them. Boone refuses, saying she is with her people. As the two sides get ready to engage in battle, Tekawitha chooses to return to the Cherokee, saying that the Indians are her family. In other words, Boone and the settlers – who thought they were doing the right thing by fighting for Tekawitha’s right to be with the “civilized” whites – were actually wrong. They didn’t look beyond her skin to see what was in her heart. They were practicing a kind of reverse racism.

You can see why the series producers chose this as the second episode to be broadcast (in the 1960s, the production and broadcast orders of TV shows did not often coincide, especially for new series, which tried to put their strongest episodes upfront). There are many bucolic family scenes, spotlighting each of the characters: Daniel doing his chores (chopping wood) and singing Israel to sleep (he sings twice in this episode – the first time is when he brazenly walks into the Cherokee camp during a war council, disarming the Indians by warbling a folksy tune); Becky singing as she cooks; Israel with his pet goose, Hannibal, and also hunting what he thinks is a possum (actually a skunk, until Daniel stops him); Jemima on the porch, combing her hair “100 strokes”; and Yadkin being, well, Yadkin (the series lost an irreplaceable character when Albert Salmi left in the second season).

There’s also a fair amount of drama in “Tekawitha McLeod” but not much action – this is a character-based, issue-oriented episode, the sort of tale the series would regularly alternate with more action-oriented episodes (the perfect blending of both action- and character-based stories were the first season’s “Cain’s Birthday” and the second season’s “The High Cumberland”).

Technically, the episode (directed by long-time ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN director Thomas Carr) is well done, although some of the studio shots of Boonesborough are noticeably different in lighting than the location photography of the Indians massing. Paul King’s teleplay works on many levels, and has some nice moments, most notably when Daniel asks Mingo whose side he will be on in the coming battle (“You would be a hard man to kill,” Mingo says, meaning, of course, both physically and emotionally), and in the aforementioned speech by Tekawitha in which she claims the Cherokee as family and also hints that Boone has actually been chasing a ghost, a dream of what might have been: “In me you see a memory – someone who should have waited.” The cast is top notch, with Parker already pitch-perfect as Boone in only his second appearance (Nice line: “Fetch Ticklicker and my bonnet,” he calls out to Israel, referring to his gun and coonskin cap). But the real surprise is Cincinnatus. Did you ever wonder hat he looked like without his beard? Well, wonder no longer.

A top-notch installment, which set the template for good things to come.

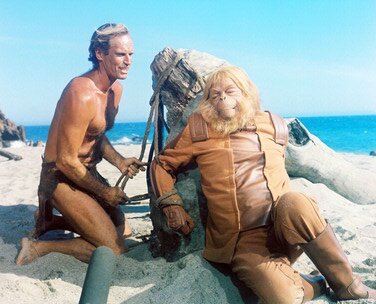

Fess Parker, with Tom Soter, 1998

Fess Parker, with Tom Soter, 1998

008 A Short Walk to Salem (#7403)

Original Air Date: 11-19-64

Written by Paul King

. Directed by Harry Harris. Produced by Vincent M. Fennelly

Fess Parker ............. Daniel

Albert Salmi ............. Yadkin

Ed Ames ............. Mingo

Patricia Blair ............. Rebecca

Darby Hinton ............. Israel

Dallas McKennon ............. Cincinnatus

James Waterfield ............. Simon Girty

Charles Briggs ............. Hiram Girty

Dean Stanton ............. Jeb Girty

Robert Sorrells ............. Luke Girty

William Fawcett ............. Ben Pickens

and Hannibal, the Goose

Daniel, Yadkin, Mingo, and Israel encounter Simon Girty and his three no-account sons, who make off with the Boonesborough settlers’ seasonal take of furs. Girty is the brains of the outfit, which isn’t saying much: not only does he steal the furs in broad daylight in front of a crowd of people, but he regularly lets his victims live – although trussed up in a way that allows them a chance at escape, albeit slim. When he robs Yad in the pre-credits teaser, for instance, he leaves him hanging upside down, trussed to a tree branch (Daniel’s later encounter with his pal, in which he jokes about Yad’s unusual method of attracting game and “saving” gunpowder is a treat – Parker at his deadpan best). Later, Girty ties Boone and Yadkin to the ground – again, giving them an opportunity to escape. (This, of course, is standard villain behavior in most adventure stories; if the bad guy just shot the hero when he had him at his mercy, there would be no story.)

“A Short Walk to Salem,” as its ironic title indicates, is a bit of Boone whimsy, the kind of Kentucky tall tale that old Dan’l might have entertained his neighbors with at a hoedown. It tells how a man, using only “what the good Lord gave him,” with a little help from ignorance, fear, and superstition, can outfox a group of surly characters with four rifles. It is a light-hearted romp, with a pair of fistfights, a lovely scene between Dan and Becky, and a delicious coda when Boone, Yadkin, Mingo, and Israel all respond in their own inimitable ways to Becky’s query: “Did you have any trouble along the way?” Indeed! This is a delightful episode, with a rousing Copland-esque score (worthy of a CD release) by Star Trek’s Alexander Courage (that is, if the closing credits are to be believed; for some reason, Ed Ames is listed as playing Mingo and Taramingo – although it can’t be the credit list from “My Brother’s Keeper,” in which Taramingo appeared, because the Girtys are listed too).

Eric Saarinen

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1396:]]

In describing the work of director/cameraman Eric Saarinen, the phrase that most often crops up is "visually striking." Saarinen, a founding partner of Plum Productions, Santa Monica, has captured images of people "driving" lions, elephants, and giraffes through a busy street, and of an automobile creating massive sand dunes in a desert landscape. The wildlife traffic jam of "Animals," an international :60 for Fiat via Leo Burnett, Milan, won a first place Mobius Award for direction and production in '99, while the desert-set "Drifts" for Chevy Tahoe out of Campbell-Ewald Advertising, Warren, Mich., took several '98 Mobius and New York Festival awards for production, cinematography, and camera work.

"I'm fascinated with the image," says Saarinen, who has directed several more Chevy ads, including "Lighthouse" and "Lifeboat" for Chevy Blazer, again via Campbell-Ewald.

Saarinen's visual dexterity comes through in "Lighthouse." The spot opens on a foggy shoreline and a lighthouse. A foghorn sounds, and light sweeps across the water. As the camera moves in on the lighthouse, the punchline becomes apparent: Rather than a bulb, the lighthouse's warning light is actually the headlights of a Chevy Blazer. The spot unfolds without dialogue, except for the voiceover at the end: "Chevy. A little security in an insecure world."

Artistic Genes

Saarinen, 57, inherited his artistic sensibilities from his mother, the sculptress Lily Saarinen, and his father, Eero Saarinen, an architect. His father's prominence in his field drove the younger Saarinen into the film world. "My dad was a famous architect," says Saarinen, "so I felt that I had to do something close to [the arts]. But I didn't want to directly compete with him. Still, in a way, I was always competing with my dad. I wanted to do something that he didn't do. It was exacerbated because everyone was sort of bowing down to him. He was a great man."

That sense of competition pushed Saarinen to create as much as possible—"overachieving," he says—in a variety of areas. As an undergraduate at Goddard College in Plainfield, Vt., Saarinen studied painting and graphic design. He later earned a master's degree of fine arts from UCLA's film production program.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1397:]]

Saarinen's first professional jobs were for low-budget producer Roger Corman, who was mentor to both George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola. Among Saarinen's more colorful credits were: second-unit camera work on Corman's Death Race 2000, and serving as cinematographer for The Hills Have Eyes, one of horror-meister Wes Craven's earliest films. (Craven is currently repped for commercials through bicoastal The Industry.)

Saarinen has since shot over a dozen feature films, including Albert Brooks' Lost In America, Real Life and Modern Romance. He worked on documentaries such as the Academy Award-nominated short Exploratorium, and a film about artists Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenburg and Andy Warhol for the Los Angeles County Museum. Saarinen also did camera work on the Rolling Stones' concert film Gimme Shelter, the TV series The Underwater World of Jacques Cousteau, and several National Geographic specials.

In '81, Saarinen circumnavigated the globe two and a half times in 13 months to shoot Symbiosis, a 16-minute, 65mm film for Walt Disney World's Epcot Center, Orlando, Fla.

Through his assignments, Saarinen has learned to search for the perfect visual. "I do my own camera work," he says. "If you're at a certain place and a certain time and you take a picture, there is some kind of permanence about that; you're memorializing the moment in a way no one else can do it. I'm half-blind, which they didn't find out until I was eight years old. Since my eyes were screwed up, I studied a lot of tricks of depth to compensate for that. I think it gives me an unusual vision."

March 24, 2000

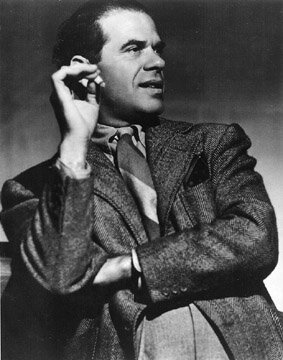

Frank Capra

IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE

The Films of Frank Capra

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 2000

Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night. The thin young man seems battered, worn down. His tie is askew and his chin unshaven, but there is a passionate gleam in his exhausted eyes as he begins to speak haltingly, with a rasp in his voice.

Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night. The thin young man seems battered, worn down. His tie is askew and his chin unshaven, but there is a passionate gleam in his exhausted eyes as he begins to speak haltingly, with a rasp in his voice.

“I guess this is just another lost cause, Mr. Paine,” he says to an older man sitting in front of him, one of dozens of senators who are watching this young speaker as he addresses the U.S. Senate. “All you people don’t know about lost causes. Mr. Paine does. He said once they were the only causes worth fighting for.” He pauses. “And he fought for them once. For the only reason any man ever fights for them. Because of just one, plain simple rule. ‘Love Thy Neighbor.’ And in this world today, full of hatred, a man who knows that rule has a great trust...”

His raspy voice is rising with passion and urgency. “And you know that you fight for the lost causes harder than for any others.” He pauses. “Yes, you even die for them.” He turns to face the crowd. “You think I’m licked. You all think I’m licked. I’m not licked. And I’m going to stay right here and fight for this lost cause...Somebody’ll believe in me!”

The climactic speech by Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) is pure Frank Capra: a combination of uncompromising ideals and relentless sentimentality. It is stirring, passionate, melodramatic, touching – “Capracorn” to some, but effective nonetheless. And although the director died five years ago, Frank Capra’s films and his influence seem to be going stronger every day.

To celebrate the centennial of the filmmaker’s birth, Columbia-TriStar Home Video has released a collection of 10 Capra classics, including the documentary, Frank Capra’s American Dream (1996) and the rarely seen Miracle Woman (1931) and Platinum Blonde (1932); the University of California Press has issued Six Screenplays By Robert Riskin (from Capra-directed movies); and the NBC television network is once again airing what has become a Christmas perennial: the soberly sentimental It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Capra’s ode to friendship.

Capra’s “touch” can be seen in modern films, as well, with critics coining the phrase “Capraesque” to describe anything that is either corny or inspirational (or both) that involves the common man rising up to back an underdog. The recent Kevin Kline comedy In and Out, for example, has a heartwarming ending that could easily have been lifted from Capra in which the population of a small town stands up to (falsely) declare its communal homosexuality in support of a gay teacher.

Surprisingly, the quintessentially American director was born in Bisaquino, Sicily. The sixth of seven children, Frank came to California with his family when he was six. After a farming accident killed his father, the youth put himself through high school and then college by working in factories and in newspaper plant. He graduated from Cal Tech with a chemical engineering degree.

After World War I, Frank spent three years drifting between jobs before he directed his first movie in 1921. He became a film editor and then a gag writer, and soon was directing silent star Harry Langdon in two of his biggest hits. A falling out with Langdon temporarily derailed the director, but he eventually signed up with Columbia Pictures, dubbed “Poverty Row” because of its low-budget efforts.

An act of desperation by the struggling Capra – who had aspired to work for the more prestigious MGM – the partnership soon became a marriage of salvation for both Capra and Columbia. Within five years of signing on, the director’s movies were generally Columbia’s biggest money-makers, as well its most critically acclaimed hits. He did everything from mysteries (The Donovan Affair, 1929) and action flicks (Dirigible, 1930) to women’s “weepers” (The Bitter Tea of General Yen, 1932) before he found his groove with screenwriter Robert Riskin.

Riskin gave Capra a focus and the two of them collaborated, in one way or another, on over a dozen movies. “We vibrated to the same tuning fork,” Capra once said of his partner. Added an observer who knew them both: “Frank provided the schmaltz and Bob provided the acid. It was an unbeatable combination. What they had together was better than what either of them had separately.”

The Capra-Riskin formula usually involved a number of elements: naturalistic performances, superb supporting characters, a hearty serving of sentiment and good horse sense, witty dialogue, and a basic plot in which a Christ-like innocent goes up against an entrenched system that nearly destroys him. The protagonist, becoming wiser in the ways of the world, would escape defeat by the love of a woman and the help of the little people. In the process, his virtue is redeemed and deepened by the experience. As the novelist Graham Greene put it, the director’s favorite theme was “goodness and simplicity manhandled in a deeply selfish and brutal world.”  Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Capra used the techniques of film – lighting, cutting, actor’s expressions – terrifically well. “[There are] moments or scenes that descriptions of the characters or summaries of the plot of the movie leave out,” wrote Ray Carney in American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra. “They are scenes or fleeting moments within scenes in which perhaps nothing is happening socially – moments, for instance, when characters simply sit still and are silent; when they look at each other but do not speak; when music swells on the soundtrack, or the rhythm of the editing changes, or a special lighting effect is employed, even though nothing is apparently happening in terms of the advancement of the plot or the dialogue spoken. Such moments, when the social situations of the characters or the lines they speak cease to express the meaning of a scene, are frequently the most important ones in Capra’s movies.”

Through such films as Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (1934), and You Can’t Take It With You (1938), Capra became known as a proponent of the common man, downtrodden in real life by the Depression. But, as Joseph McBride points out in Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, the irony is that Capra himself was a conservative Republican and fan of the dictator Mussolini, who voted against Franklin Roosevelt four times because he was afraid the Democrat would redistribute the director’s wealth, much as his own Mr. Deeds wants to do at the end of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936).

“Like the popular artist he was, Capra was being led by his audience,” observed McBride. “They were demanding reform, they were demanding social welfare programs and redistribution of wealth, they were angry at the shortsightedness and greed of big business and the Republican party. The sense of brotherhood and compassion that came from Riskin’s writing and began to open up the narrow vision of Capra’s work brought him into closer contact with his audience, giving his work a deeper and more popular resonance, putting him in touch with a sense of community for which he previously had little feeling.”

Capra was also successful because he had the savvy and good sense to partner with collaborators who would increase his strengths as a cinematic storyteller, from cameraman Joseph Walker’s sophisticated lighting techniques to screenwriter Riskin’s clever characters, construction, and dialogue. “Capra in the prime of his career liked to surround himself with colleagues who were not yes men, and his ability to listen to and absorb such a range of viewpoints...[contributed] to the complexity of his films,” wrote McBride.

Capra’s choice of leads – his favorites were Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Barbara Stanwyck – is also indicative of his shrewdness. “Each of them brought to a role almost the opposite of the ‘star quality,’” wrote Carney. “They represent a vacancy, blankness, or indefiniteness that...is exactly right for Capra’s investigations of the achievement of identity....They are figures of desire or inarticulate idealism searching for a cause to follow, a leader to embrace, or a satisfactory form of personal expression...”

From 1930 to 1939, Capra seemed to be able to do no wrong: he had few failures and won three Academy Awards as best director. But during the war (when he was the producer of the acclaimed Why We Fight propaganda movie series), he seemed to lose his way. Some say the regimentation of the army dampened his enthusiasm, others argue it was the brutality and suffering he saw in the newsreel footage he gathered for Why We Fight. Whatever the reason, the Capra who returned from the war was a changed man.

His first post-war movie was It’s a Wonderful Life. Although now hailed as a Christmas classic, the film received mixed reviews on release and was a commercial failure. Capra himself worked on the screenplay, the story about a frustrated man who wishes he had never been born. A darkly moving parable about survival, it is brims with anger and pessimism, which some have argued was what Capra himself was feeling at the time.

“It’s a Wonderful Life is a film of endless frustrations, deferrals of gratification, and of the complete impossibility of representing the most passionate impulses and imaginations of the self in the world – and yet the title is still entirely unironic,” observed Carney. Bailey’s life is wonderful because “he has seen and suffered more, and more deeply and wonderfully, than any other character in the film.”

After that, the spark was gone. Ironically, the conservative Capra was pursued by the federal government as a possible Communist and secretly named names. The man whose characters championed lofty principles and “lost causes” himself caved in and was never the same again. In the 1950s, he was reduced to remaking his past classics, filming Broadway plays, and creating TV shows for children. By the 1960s he had retired, although in 1972 he offered his last work of fiction: an “autobiography” that was self-aggrandizing, apparently largely untrue – and a big hit. It made the man a star all over again.

By the time he died in 1991, many critics were still divided on whether Frank Capra was a great filmmaker or just a great fraud. But one thing everyone did agree on was that the director’s best movies had helped define his country. “Maybe there really wasn’t an America,” filmmaker John Cassavetes once observed. “Maybe it was only Frank Capra.”

Romantic Comedies

Wiliam Powell and Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey.

Wiliam Powell and Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey.

The Changing Nature of

ROMANTIC

COMEDIES

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 2000

My ex-girlfriend, Michele, was a screwball. A romantic screwball, but a screwball nonetheless. She was beautiful, bright, and befuddled, talking in paragraphs, not sentences, with barely a breath between words. You would ask her one thing and she would answer a dozen – usually going off on tangents you never knew existed.

Conversations with her sometimes reminded me of one Irene (Carole Lombard) has with Godfrey (William Powell), the man she loves, in My Man Godfrey (1936): “You’re more than a butler. You’re the first protege I ever had...Like Carlo...He’s mother’s protege. It’s awfully nice Carlo having a sponsor because he doesn’t have to work and gets time for his practicing but then he never does and that makes a difference...Do you play anything, Godfrey? Oh, I don’t mean games or things like that, I mean the piano and things like that...Oh, it doesn’t really make any difference. I just thought I’d ask. It’s funny how some things make you think of other things.”

Other times, I would feel like David (Cary Grant) in Bringing Up Baby (1938), when he tells Susan (Katherine Hepburn), “Now, it isn’t that I don’t like you, Susan, because, after all, in moments of quiet, I’m strangely drawn to you, but – well, there there haven’t been any quiet moments.”

Yes, Michele would fit right into a romantic comedy.

Romantic comedies – especially the screwball variety – are known for their beautiful, batty women whose fast speech and zany actions often conceal a brainy purpose (usually to land a man) but are equally noteworthy for their outlandish plots and their “sentimental cynicism.”

The heyday of the romantic comedy was from the mid-1930s through the mid-1940s, when crisis and change in American life left people feeling as dizzy as the befuddled guys listening to those wacky girls. Now, nearly 70 years later, some are saying that we have entered a new era of wild romances, inaugurated by When Harry Met Sally (1989) and continuing to this day with such recent entries as Notting Hill, Runaway Bride, and The Next Best Thing. Yet today’s retro romances – although sharing similarities with their zany predecessors – also have significant differences.

The modern romantic comedy began inauspiciously enough with Frank Capra’s low-budget It Happened One Night (1934). No one had much faith in it and Hollywood insiders predicted disaster. Its surprising success, however – best picture, best director, best screenplay, best actor, and best actress Oscars – led to a rash of romantic comedies.

The best of these feature what could be called the Classic Plot, starting with the boy meeting the girl in a situation guaranteed to make one or both of them dislike the other. Top Hat (1935) finds Jerry (Fred Astaire) dancing so loudly in the room above Dale (Ginger Rogers) that she angrily confronts him. (He: “Every once in a while I suddenly find myself dancing.” She: “I suppose it’s some kind of affliction.”)

Usually, the story has a heroine who’s either smarter than the guy, daffier than the guy, or colder than the guy. In the course of the movie, she will sequentially despise him (but still get entangled in his affairs), come to admire him (even as she fights with him), and finally realize she loves him. In the process, she will also change from spoiled or cold or daffy to concerned or warm or slightly less daffy. Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story.

Cary Grant and Katherine Hepburn in The Philadelphia Story.

Then there’s the man. He’s either a surface cynic, using a wisecrack to cover his feelings (Claudette Colbert to Clark Gable in It Happened One Night: “Your ego is absolutely colossal.” Gable: “Yeah. Not bad. How’s yours?”), or else hopelessly repressed and befuddled. In the first instance, the heroine brings out the romantic in the hero, as he comes to realize that there’s more to her than he thought. In the second case, the hero realizes that there is more to life than being straitlaced.

The battle of the sexes is another key element, along with the other classic ingredient: the almost childlike nature of the heroine, who constantly defies convention and thereby helps unstuff the hero’s shirt. There’s a child inside of all of us, say these movies, repressed by the constraints of society. To be slightly crazy and in love is to be imaginatively free.

The unlikely pair will find themselves thrown together and face various obstacles to finding love. The most popular impediment is having the man/woman already engaged to someone else whom the audience (but not the character) can see is terribly inappropriate. In Holiday (1938), Cary Grant’s Johnny is a free-spirited soul who meets a kindred sort in Linda (Katherine Hepburn), the sister of the woman he thinks he wants to marry (Doris Nolan). He sees only his fiance’s surface beauty and charm, not the inner, conservative side to her.

The pair also can come from different worlds. In Pat and Mike (1952), Pat (Katherine Hepburn) is about to marry a man who is inappropriate for her but she doesn’t know it. She meets Mike (Spencer Tracy), whom she initially mistrusts. He is rough-and-tumble, while she is oh-so-elegant. Naturally, they fall in love.

There is also, inevitably, the Grand Misunderstanding – the hero has a girl back home (Swing Time, 1936) – which leads to the Final Reconciliation.

Such comedies are immeasurably helped by the wonderful romantic pairings of star couples with a unique chemistry: sexy sophisticates William Powell and Myrna Loy (12 appearances, six as sleuths Nick and Nora Charles); the “he gives her class, she gives him sex” team of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (10); and the “tough guy and the lady” duo of Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn (9).

The formula and the couplings lasted right up to the Rock Hudson-Doris Day comedies of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Those movies added a bizarre subtext not seen in the classic period. Pillow Talk (1959), for instance, seems to be a frothy bedroom farce about an amoral playboy (Hudson) who takes on another identity – a naive Texan – to woo a woman who can’t stand him. But because it lacks the light touch and moral center of the classic romances, the movie plays as an exploration of deeply disturbed people who lie, cheat, and betray without compunction.

Hudson’s playboy, Brad Allen, is possibly the most despicable leading man ever seen in a light comedy: he manipulates perky working woman Jan Morrow (Day) into falling in love with him and almost sleeps with her. And why not? Marriage is described by many of the characters as an emasculating trap.

Pillow Talk and the other Hudson-Day spoofs were huge successes, but also the last gasp of the traditional romantic comedy formula. By the late ‘60s, the genre had been transformed. Romance was out; rebellion and sexual revolution were in. Films like The Graduate (1967) celebrated youth and rebellion not convention, while the easy-loving James Bond adventures put the final nail in the coffin of old-fashioned love-making.

The man who helped bring back and also change the idea of the romantic comedy was, of all people, that unromantic nebbish, Woody Allen. The pinnacle of the Allen oeuvre, Annie Hall (1977) is the story of Alvy Singer (“a real Jew”) and Annie Hall, a whitebread neurotic who learns from, loves, and, finally, leaves Alvy. Allen’s film is a meditation on the impermanence of life and love, of how everything changes but the memory lingers on.

The film is brilliantly constructed as a comic reminiscence, starting off with Allen’s to-the-camera statement, “Annie and I broke up and I still can’t get my mind around that,” and leading, by degrees from the middle, to the beginning, and then to before the beginning of the relationship. Along the way, we learn about Alvy’s obsessions, about his kindness and cruelty, his selfishness and his sexuality.  Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in The Lady Eve.

Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in The Lady Eve.

The difference between this and the romantic comedies of the earlier era is its obsession with “me, myself, and I.” Everything is reflected from the prism of Alvy’s consciousness, giving the movie a point-of-view that is at alternate times romantic, comic, and selfishly melancholy. But it is always terribly insightful and more realistic than most of the classic romances ever were.

Allen’s approach took flower among recent filmmakers who further transformed the romantic comedy: In The Real Blonde (1997), writer-director Tom DiCillo effortlessly skewers the obsessions, neuroses, and self-centeredness of actors and other media, while also presenting a funny, sad, and maddeningly real portrait of men and women trying to connect. DiCillo has a keen understanding of his character’s frustrations and fantasies. Indeed, as a soap star searches for his ideal, a “real blonde,” the movie makes it clear that the world is not about seeking perfection but settling for imperfection.

Other recent romantic comedies, however, simply ape the forms of the past. Typical of these is Runaway Bride (1999), a TV sitcom version of the great screwball comedies of the ‘30s, with Richard Gere as a cynical reporter and Julia Roberts as willful would-be bride, immature and unsure of what she wants from a man. The movie is by the numbers, though, with Gere and Roberts hating each other for the first third, discovering and then respecting each other in the middle, and falling in love in the final section.

Nonetheless, the best of the new crop brings romance back with gusto, such as Notting Hill (1999), a charming, if unlikely, love story about (British) boy meeting (Hollywood movie star) girl. Following the romantic comedy formula faithfully, it is made enjoyable by the chemistry between shy Hugh Grant and tough-but-vulnerable Julia Roberts.

In a way, it’s no surprise that romance in the movies has returned. With uncertainty in the world, audiences seek the safety of convention. And what safer convention can there be than sentimental, ever-lasting movie love?

Indeed, only in Hollywood can you find romance as gloriously triumphant as it is in the beautiful climax to The Lady Eve (1941), when Eve (Barbara Stanwyck) exclaims to her lover (Henry Fonda): “Why didn’t you take me in your arms that day on the boat? Why did we have to go through all this nonsense? Don’t you know you’re the only man I ever loved, you big fathead? Don’t you know I couldn’t look at another man if I wanted to? Don’t you know I waited all my life for you...you big mug?”

The Shoot Collection

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1395:]]

Here is a collection of commercial industry stories that I wrote for the trade publication SHOOT.

Friday June 2, 2000

SPECIAL REPORT: NEW YORK PRODUCTION_ New York, New York: A look at production in the Big Apple.

Call it an "only in New York" kind of story. Hurricane Floyd was set to hit the city the same day director Nick Cassavetes of Creative Film Management (CFM), New York, was going to shoot a campaign called "Confessions" for The Travel Channel in Central Park. The spots, out of M&C Saatchi, New York, featured various characters talking about their obsessive shopping for items they dont need in order to get airline miles.

A hurricane about to ruin a shoot? Should they reschedule? Lou Addesso, president/founder of CFM, says his people are New Yorkers through-and-through: unfazed, unflappable, and thoroughly professional. With the threat of the storm, Cassavetes and his crew turned on a dime and found new indoor locations. They even managed to keep one outdoor shot: a woman standing in Central Park under a bright blue umbrella, the sky dark and threatening.

"It was fabulous," recalls Addesso. "We had the run of city because everyone was leaving because of the hurricane. We changed most of the locationsathe one in the park was ominous-looking and beautiful. Because of the depth of talent in the New York crews, they made the transition so natural. It was seamless."

Addessos "can do" attitude is typical of the city that never sleeps and may help explain why film and television production in the area is up. For five of the past six years, the Mayors Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting reports that TV and film production in New York City has reached historic levels, the high water mark being 98. However, 99 is just slightly off from that record previous year. Direct expenditures on location shootingathe city breaks down expenditures based on permits issuedaran steady in 99 with $2.52 billion compared to $2.56 billion in 98. That makes 99 the second highest year of the record-breaking six-year run from 94 through 99. In a breakdown of costs from 99, commercials accounted for some $337 million of the $2.52 billion total. Although the overall tally for production was down slightly in 99, the city experienced record growth in television, leading with 13 prime-time series being produced, which accounted for $1.29 billion in '99, compared to $1.24 billion in 98.

A number of commercial production houses say that their work contributes to the bottom line of production in New York. Barbara Gold, executive producer of Five Union Square Productions, New York, reports that "this year, seventy-five percent of our work has been in New York." That includes several ads for Geico Insurance, such as "Airlift" and "Mystery Customer," directed by Tom Schiller via The Martin Agency, Richmond, Va.

"Twenty to thirty percent of work we did in the last year was shot in New York City," says Charlie Curran, an executive producer at Crossroads Films, X-Ray Production and X-1 Films, all bicoastal and Chicago. "Its usually location stuff." Recent New York work from director Russell Bates of X-Ray includes Keyspan Energys "Coffee Shop" and "Taxi" out of Earle Palmer Brown, New York. And Bruce Hurwit of Crossroads helmed "Train" for Dunkin Donuts via Hill, Holliday, Connors, Cosmopulous, Boston.

Friday, Feb. 18, 2000

SPECIAL REPORT: MUSIC & SOUND DESIGN - The top three tracks prove that sometimes all you need is music.

For SHOOT's Winter Top 10 spot tracks, the top three spots all have one striking characteristic in common: they contain almost no dialogue and are driven mostly by their soundtracks. The Web site eTour, that connects users with sites of interest, used the image of a plane driving through suburbia in "Aviation." The score for the ad is an industrial piece that propels the action, and according to Kevin Roddy, a creative director at Fallon McElligott, New York, it was necessary for the spot to have a strong score. "We felt the music needed to have a driving beat, sort of mechanical," explains Roddy. "It's a plane and we wanted the music to reflect that."

IBM's "Supermarket" is accompanied by a playfully sinister piece of techno music, which is underscored by subtle sound design. The spot depicts a man who is presumably shoplifting. The agency and the music house worked on the track for four weeks, experimenting with several styles of music before eventually going with the techno composition. "Shoplifting can look like you're having a good time, or else it can be dark and sinister-we wanted to skew it more to the fun side," explains Brian Banks, the composer for the spot.

CNET's "Dance" features a rather awkward couple dancing together to illustrate how CNET. com helps consumers find the right technology products. The spot is backed by a basic and ethereal tune, something the agency felt was necessary for the spot's success. "We wanted something really, really simple, especially for television, where you see all the ads for dot com companies and they all try so hard to see who can outdo the next company," explains Leagas Delaney copywriter Matt Elhardt. Following is a look at how the music and sound design for the top three was created.

Friday, Feb. 11, 2000

SPECIAL REPORT: TEXAS PRODUCTION & POST: Moving In - Texas cos. have a few new neighborsnand not just geographically. When creating commercials, more and more out-of-town production companies are finding the Lone Star State is the place to be. In recent months, that notion has led to the formation of alliances between out-of-state production houses and homegrown, Texas-based shops for a variety of reasons, including a desire to increase one's presence in the Texas agency market, as well as to expand production options.

In one deal, bicoastal Atherton entered into a reciprocal agreement with Concrete Productions, Dallas. In another, New York-based Washington Square Films formed a relationship with Directorz (formerly Bednarz Films), Dallas. Per the latter arrangement, Washington Square directors Jeff Feuerzeig and Peter Sillen are represented in the Southwest by Directorz.

Texas has long attracted production companies from other areas. Mark Androw, executive producer of the Story family of companies-New York Story, Chicago Story, L.A. Story and Texas Story-has had a base of operations in Texas since '92. When Androw started Chicago Story, the first of his companies, in '89, the idea was to offer, in his words, "national quality directors for local production, with local production support." In '93, Androw branched out with New York Story, and followed with L.A. Story in '95.

Harvest

Harvest, which was started by director Baker Smith and executive producer Bonnie Goldfarb in March 2001, made an impressive showing on the awards circuit this year. The company's winning package was a three-spot campaign for FOX Sports out of TBWA/Chiat/Day, San Francisco, comprising the ads "Nail Gun," "Boat" and "Leaf Blower." The commercials, which show what happens to items haphazardly assembled during the baseball playoffs, earned honors at the Cannes International Advertising Festival, the AICP Show, the Clios, The One Show, the British Design & Art Direction (D&AD) Awards and the ANDYs.

Goldfarb believes that Harvest's impressive showing is a result of the Santa Monica-based company's small size. In addition to Smith, Harvest represents directors CJ Waldman and Frank Samuel. "We are very conservative in the way we manage our money," explains Goldfarb. "We have set up a business model in which we have very low overhead. We don't have offices in London, New York, or Paris. Larger companies have a large payroll, which is dependent on gross numbers. And satellites tend to fragment the brand.

"We are not in business to manage an overwhelming and unwieldy infrastructure of masses of staff employees," Goldfarb continues. "We have purposefully designed our offices to house a kitchen where everyone meets for lunch, music is constantly flowing through speakers throughout the building, and yoga is offered twice a week at no charge to staff or freelancers. This atmosphere has allowed not only our directors but also our agency and client friends to feel relaxed and welcome."

Besides size, flexibility is a crucial in Harvest's success. "You have to be flexible as a company, to give and take with each and every board that comes in," she says. "You have to be able to read [the requirements of] the boards, to read the client, to read the agency, and to know how to produce the commercial. That's a reflection of the times: prep is shorter and you have to be cognizant of how you're scheduling your directors. That's how we got FOX Sports. Besides the financial and artistic considerations, we were able to accommodate the client on the schedule."

HSI PRODUCTIONS

HSI Productions has grown dramatically since it opened its doors over 16 years ago—from a one-director shop to a an operation with 20 directors (of commercials, music videos, features, and other projects) and over 60 employees—but one thing that hasn't changed is the company's concern for quality and diversity.

On the quality front, the bicoastal company had a strong showing at this year's awards shows. Nike's "Freestyle," directed by Paul Hunter via Wieden+Kennedy, Portland, Ore., scored honors at the AICP Show and the Clios. Gerard de Thame, who directs via HSI and Gerard de Thame Films, London, earned honors at the AICP Show for Mercedes-Benz's "Modern Ark," out of Merkley Newman Harty|Partners, New York; additionally, Aquafina's "Summer Heat," directed by Irv Blitz, also scored well at the AICP Show.

The key to such quality, explains company founder/president Stavros Merjos, is diversity. In addition to working on commercials, music videos, graphics, and features, HSI has a new print division (in association with Smashbox) called Mercury Artist Group. In July 2002, HSI signed a two-year, first-look pact with New Line Cinema, and two months ago, it opened Exposure, a music video and commercial company based in London.

"Diversity makes us stronger," Merjos says, noting that HSI draws in new clients who want multitalented directors. He cites the versatility of his helmers as a selling point, since they are as at home shooting commercials as they are at crafting original concepts, a common practice in the music video world. In addition, Merjos believes the breadth of work in which HSI is involved is a corporate strength because it helps amortize costs over a range of projects so "we are not dependent on one job or one industry."

The awards are nice, Merjos adds, but it is the work—and the repeat business—that tells the tale. "Attention is good in any way you can get it," he notes, "but the best way is to have an amazing commercial. People don't give you as job just because you won an award."

Friday, Dec. 5, 2003

SPECIAL REPORT: AGENCY OF THE YEAR_ New Frontiers

Rupert Samuel, co-director of broadcast production at Crispin Porter + Bogusky (CP+B), Miami, had never worked with Spike Jonze of bicoastal/international Morton Jankel Zander (MJZ), until Ikea's "Lamp," which began airing late last year. The collaboration was a long time coming—Samuel had sent the director many scripts, and Jonze finally agreed to one that caught his eye: "Lamp." The concept was appropriately bizarre for the director of Being John Malkovich and Adaptation; it featured an abandoned lamp that was meant to evoke sympathy from viewers.

Jonze and the CP+B team transformed the simple concept into an award-winning ad. The spot scored the Grand Prix at this year's Cannes International Advertising Festival, and the Grand Clio at the Clio Awards, among other accolades. "Lamp" features a mournful piano tune, which accompanies images of a woman unplugging a desk lamp, taking it out of her apartment, and leaving it downstairs on the street with the rest of her garbage. We see the lamp, desolate and alone by the garbage can, as rain begins to fall. The lamp seemingly stares at the window of its former home, where a new lamp has taken its place. Then comes the kicker: a man with a Swedish accent steps into the picture and addresses the audience: "Many of you feel bad for this lamp. That is because you [are] crazy. It has no feelings. And the new one is much better."

"Spike brought [the concept] to life, adding rain and the big city scene," recalls Samuel, who along with David Rolfe, co-head of broadcast production, oversees an 11-person production department at CP+B. According to Samuel, this sort of methodology is typical of the agency. "[CP+B] creatives often offer up a script with room for ideas to be put in," he notes. "The basic idea for 'Lamp' is you feel bad for an inanimate object. But how do you make it sing? That's where collaboration comes in."

Collaboration is the name of the game at CP+B, SHOOT's 2003 agency of the year. So is success. The agency has a long track record of producing highly creative spots, winning awards, and enticing topnotch directors, both emerging and established, with clever concepts and creative freedom. Besides Jonze, the agency production team has collaborated with Happy—a.k.a. Guy Shelmerdine and Richard Farmer—of bicoastal Smuggler, who recently directed a series of spots for the TV show Nip/Tuck on the FX Network. (Those spots were done via the Los Angeles office of CP+B; producers from the Miami home base produced for the outpost.)

StyleWar, an up-and-coming Swedish directing collective with Smuggler, has also worked with CP+B, as have spot veterans such as Bryan Buckley of bicoastal/international Hungry Man and Baker Smith of harvest, Santa Monica. Smith, the winner of this year's Directors Guild of America (DGA) Award for best commercial director, scored that honor in part on the basis of "Clown," a spot for the Mini Cooper, out of CP+B.

The agency owes its success, in large part, to the trusting give-and-take that was demonstrated in the creation of "Lamp." According to Rolfe, the agency producers and creatives pride themselves on their ability to leave their egos at the door and accept ideas from anyone. The goal is not to earn points for coming up with a concept, but to create the best possible spot.

"It felt like you weren't fighting against each other, you were together fighting something else," recalls Oskar Holmedal—one of the directors in StyleWar—about the experience of helming a new package of Ikea spots for CP+B. "It was really good. You had respect for all of their ideas and thoughts. We just threw everything in there. There was no holding onto anything for ego. It was just a search for good ideas."

Take "Clown," directed by Smith, for example. In it, a clown jumps into a Mini and squirts the driver in the eye as he's negotiating the car down a winding road. Rolfe says the spot was funny as shot, but that during the editing process, discussions with Smith, partner/executive creative director Alex Bogusky, and editor Paul Kelly of 89 Editorial, New York, led to a radical change in the spot. "Clown" was converted to black and white, grain was added, and a silent movie-style piano track was recorded.

"We wanted to push the envelope," explains Rolfe. "We wanted to make [the idea] unique. You don't see a car commercial that looks like this that often. Everybody was excited by the changes and by the final result, including the client."

"I thought that was fantastic," says Smith. "I thought the creative was great. … The producers will give you boards and then expect the director to take it to the next level, not just shoot the boards. If something comes up in the process of shooting or editing, like in 'Clown,' everyone embraces it. 'Clown' started out one way and then ended up as something completely different—and better."

Rolfe says he and his fellow producers have very specific criteria. "We maintain overall stewardship of the idea, but we want the directors to take risks," he adds. "We look to what the director wants to bring to it. I don't think anyone out there challenges directors as much as we do. They're not used to being pushed; they are used to being restrained."

"Doing a commercial is like staging a ballet in a phone booth, and [CP+B's] approach both stretches you and challenges you, which is fantastic," says Smith. "It's what we thrive on. You are limited to a certain degree in advertising. You have a certain set of rules that just can't be broken. But how can you bend them?"

Good Product

Such an attitude helps build trust between the directors and the producers, which leads to better creative. "There's a tremendous amount of mutual respect here," says Sara Gennett-Lopez, who stepped down last year as head of broadcast production, and is now VP/broadcast business manager for the agency. "Everyone has respect, and that goes into the work that comes out."

The agency cultivates solid concepts by searching out new directors based on chemistry rather than previous experience in a particular ad genre. "In order to make a splash, you have to do truly fresh and unique work," observes Rolfe. "You want to keep things fresh and find new talent, to go outside the more obvious talent pool."

"Pony," an effects-driven Ikea spot produced by Rolfe, is a good example. The commercial, directed by StyleWar, who also directed "Thugs" and "Bedroom," finds a couple and a young boy lounging in a living room. A voiceover begins, "Maybe you have one hundred dollars," and the room magically transforms itself—new furniture slides into place as the family goes about their business. "Maybe you have four hundred and fifty dollars," the voiceover continues, and the room changes again. "Maybe you have one thousand four hundred dollars." Another change. "Maybe you have one million dollars." Now the room is at its most elaborate, with the woman playing a new harp, and the boy on a pony that has been added to the room. "Or maybe not," the voiceover concludes, as the room transforms back to an earlier incarnation. The tag: "Help yourself to unböring."

Rolfe says that he chose StyleWar—who was featured in the Saatchi & Saatchi New Directors Show- case at Cannes this year—as director because he "wanted to work with someone with a totally different, totally unique aesthetic. [StyleWar] had not worked on the ad side, but had done music videos," Rolfe points out. "They had a unique sense of freshness, and totally lacked cynicism."

The producers' acknowledge that they are on a conscious quest for chemistry. "We look for computability between us and them," says Samuel. "We want to get along with people who love the project."

"If a reel is not full of spots similar to what you are doing, you don't simply bypass that reel," adds Rolfe. "Chemistry, understanding and unity of purpose are more important than whether he has something like it on tap."

The secret to keeping their work cutting edge, says Rolfe, is in trusting their collaborators, and never playing it safe. "Unswervingly, you have to take risks," he says. "It's almost like it has to challenge the audience. The process has to be challenging. It's always our job to bring something fresh and new. That's what the broadcast production department has to do, and what Alex has asked everyone to do from the beginning."

"Their work is all about innovation and risk-taking," says Happy's Shelmerdine. "Agencies are judged by their product. At Crispin, they just make sure they kick ass better than anyone else."

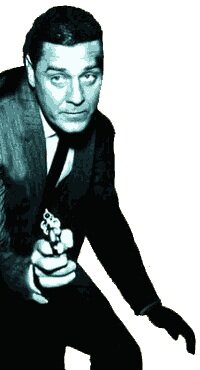

The Avengers

Macnee and Rigg.

Macnee and Rigg.

THE AVENGERS

Boxed Sets, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968

BEST OF THE ORIGINAL AVENGERS

A&E Home Video

from SCARLET STREET, 2001

THE AVENGERS is back. A&E has been releasing DVD sets of the 1961-69 series for the last two years and now a viewer can sample almost everything that’s good, bad, and just plain silly about the unique British spy show. The program began life in 1961 as a vehicle for Ian Hendry, an up-and-coming star on the short-lived POLICE SURGEON. Hendry was paired with debonair Patrick Macnee as a suave but mysterious undercover operative named John Steed. The series, fairly conventional, was transformed in 1962 when Hendry left and his part was filled by a pre-GOLDFINGER Honor Blackman.

The actress starred as Mrs. Cathy Gale, a brainy beauty given to wearing tight black leather as she physically manhandled her foes. Partially modeled on Margaret Mead, the anthropologist, and Margaret Bourke-White, a well-known Life magazine photographer who handled dangerous assignments, Mrs. Gale was an anomaly for her day: a capable, independent, and beautiful female adventurer. Steed was unusual, as well. In his Edwardian outfits, bowler hat, and rolled-up umbrella, he was less a James Bond wannabe and more a parody of the British gentleman spy as seen in Alfred Hitchcock’s thrillers THE 39 STEPS (1935) and THE LADY VANISHES (1938).

The series went through many transformations during its long run: it began as live-on-videotape, with a studio-bound look, then went to black-and-white film, then to color. Its tone changed from dead serious to mock serious to serious mockery – and then to outright absurdity. As the tone changed, so did the cast: Blackman was replaced by the curvy Diana Rigg (as Mrs. Emma Peel) who was in turn replaced by the buxom Linda Thorson (as Miss Tara King). Through it all, the one constant was Macnee’s Steed, the one fixed point in a changing AVENGERS.

A&E has not yet released the 1962 season on DVD – the 1961 Hendry shows are lost except for “The Frighteners” – but you can catch one 1962 episode on THE BEST OF THE ORIGINAL AVENGERS compilation DVD. “Mr. Teddy Bear” is typical of the Blackman series. In it, Steed and Mrs. Gale trail an international assassin known as Mr. Teddy Bear. Almost all the later elements of the program are here in nascent form: Steed bantering with his leather-clad female partner; a bizarre murder or two; and a tongue-in-cheek approach to death. In typical style, the villain gives his instructions through a stuffed bear (an idea that was partially adapted for the dreadful big-screen Ralph Fiennes-Uma Thurman AVENGERS ). Because the show was shot live-on-tape, however, both the dialogue and the action sequences frequently come across as stilted.

The different approaches of the Blackman-Rigg year can best be seen by comparing “Don’t Look Behind You,” from the 1963 collection, with its color remake, “The Joker,” available on the 1967 set. In both versions, the heroine is trapped in a spooky mansion, menaced by an unseen madman. Macnee, in a commentary on BEST OF, says that it is arguable which version is better. Short argument. “Don’t” is dull, “The Joker” infinitely superior, long on moody atmosphere, clever set design, and top-notch performances.

In fact, you could say the same about almost all the Rigg-Macnee installments, which are, by and large, a joy to behold. For an early Rigg adventure, try “Death at Bargain Prices” (on the 1965 set), directed by Charles Crichton (A FISH CALLED WANDA). The story concerns strange goings-on at a department store: after a top agent is murdered there, Steed and Mrs. Peel discover a mad millionaire who is planning to blow up London with an atomic bomb. Steed uses a ping-pong gun, Mrs. Peel wears a leather outfit.

In “Too Many Christmas Trees,” another excellent adventure (also from the 1965 set), Steed is plagued by recurring nightmares featuring a satanic Santa Claus. Mervyn Johns (the dreamer in DEAD OF NIGHT) guest stars as a man obsessed with Dickens. This episode is top-drawer: moody and atmospheric, with a touch of fantasy/sci-fi tossed in to the mix; there is also an homage to the hall of mirrors sequence in LADY FROM SHANGHAI as Mrs. Peel is stalked by a gun-toting Santa Claus. Leave it to THE AVENGERS to do a Christmas story featuring a murderous Father Christmas.

Finally, there is Tara King, Steed’s fourth partner (his final female partner was Joanna Lumley, before ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS, who co-starred with Macnee in the 1976 revival THE NEW AVENGERS). By 1968-69, the series was almost an outright farce, eschewing the balance between comedy and thrills that had worked so well in the Rigg years. “Look (Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One)...” from the recently released 1968 set, is very arch comedy, going over the edge into the world of high-camp. The story showcases two killer clowns, old vaudevillians – vaude villains, if you will – who don’t accept that vaudeville is dead; in fact, their jokes kill – literally. John Cleese, pre-MONTY PYTHON, and well-known Brit comedian Bernard Cribbins have featured parts as eccentric victims. Contrary to popular opinion, Thorson is fine as the heroine – winsome and sweet, a welcome change from the hard-edged Blackman.

“All Done With Mirrors,” also from 1968, finds Tara on her own, investigating the theft of secret documents from a top-secret naval installation. Steed is written out and Tara is partnered with a nitwit agent named Watney who does very little. The plot is thin, and the series is clearly running on empty, repeating incidents from previous episodes. As it is, you have to make due with one good fight sequence and some cool camera angles.

Except for the Blackman episodes, the sound and image quality on all the sets is excellent. As for extras, there are publicity stills on every set and the BEST OF collection has introductions by Macnee (in which he reveals some deathless trivia: did you know that Blackman’s leather outfits were green not black because of the limits of then-current technology?) A & E has also included a couple of rarities on BEST OF: the U.S.-only opening credits sequence for the 1965-66 season and a short film shot to promote Thorson. All in all, a tip of the bowler hat for the return of this memorable series. – Tom Soter

Patrick Macnee

We're needed: Patrick Macnee and Diana Rigg.

We're needed: Patrick Macnee and Diana Rigg.

THE AVENGER

RETURNS

By TOM SOTER

for SCARLET STREET, 2000

Patrick Macnee is on a tear about his wife’s dogs. “David Frost once asked me why I refused to return to England. And I said, ‘Frankly, until you let my wife’s dogs into the country, [I refuse].’ They haven’t...because of rabies. My dogs haven’t picked up even a tick in 12 years. But they’re letting all the human rabies into Great Britain at this very moment as we speak through the Channel Tunnel – I call it this monstrous hole – and yet they won’t let [in] my wife’s little dogs. And David Frost said, ‘I think they’re changing the rules’ – which they just have last week, for every where in the whole world, including Slovonia and behind the Ural mountains and the depths of Istanbul. But they haven’t from the United States because it’s such a dirty, rabies-ridden community. The irony one has to employ to sort of understand the people who [make these laws]... they don’t let two little dogs in because of the quarantine. I find the anomaly quite ludicrous.”

It is a passionate monologue – a rant, even – quite unlike what one would expect from the man who was the elegant, oh-so-proper English gentleman spy, John Steed, on television’s long-running The Avengers. Macnee is in the news once again because.The Avengers is back in crisp new DVD and video incarnations from A & E Home Video. After years of being seen in fading, worn-out prints – often as pirated tapes – the new editions are a revelation.

For that, fans can thank Macnee. He unearthed the original negatives and was responsible for sorting out copyright and ownership questions – there were claims that the series was in the public domain – and then facing down the video pirates to court. “We defeated the pirates,” says the 78-year-old Macnee. “It was an eight-year undertaking. It’s interesting to read in the Los Angeles Times how surprised they were at the success of the newly constituted, digitally restored Avengers. And they have sold one million units in less than a year.

“Now, it’s funny that A & E Networks should put that out, particularly as I have two-and-a-half percent of the profits. But for me and my accountant, this situation wouldn’t exist at all because they were being pirated for 35.years. In other words, you see in sleazy video stores a sort of sleazy cassette way in the back which was called The Avengers. And it had been taken from showings on television with commercial breaks. It was in an excreable state. So they suddenly had to pay us an enormous amount of money and it’s made life a lot easier for me. It’s given me a sort of old-age pension...And I don’t have to turn up for work every morning at 5:30. I’m laughing. That’s the story basically.”

Not quite the whole story, however. Born in 1922 to an upper-class English household, Patrick Macnee was brought up with “good manners” – but also learned quickly to appreciate and sympathize with the bizarre. At an early age, his mother left his father, an alcoholic racehorse trainer, and took the young boy to live with her lesbian lover. Known as Uncle Evelyn, the lover. paid for Patrick’s schooling at Eton.

“What was eminent about that bringing-up is that a man was not allowed in the house at all,” Macnee says. “They had to come in through the back door. All the people who worked on the farm were never allowed in the house. I think they allowed the men once a year for pheasant shooting in September. Now, I took it for granted that I lived with lesbians. I didn’t even know what lesbians were. I just didn’t see any men, that’s all. But I didn’t grow up homosexual because I’m not homosexual. I can’t take any credit for that. I just like women.”

At public school, Macnee developed an interest in acting. After five years at Eton, the Macnee family had a run of bad luck, and their finances dwindled. On the advice of the actress Margaret Rawlings, he applied to Webber-Douglas drama school in South Kensington and won a scholarship. He stayed for a short time and then moved into repertory theater. He found a variety of roles and also met his first wife, Barbara Douglas, during run of Little Women.

In 1941, he joined the navy, where he was part of Eighth Gunboat Flotilla at Dartmouth. “I sometimes say to my wife, ‘Darling, look, don’t repeat everything, don’t talk to me as though I were a small child. Please, I was a naval officer in the second world war. For five years.’ ‘Oh, were you? Where were you?’ I say, ‘In the channel in the North Sea. I was at D-Day.’ ‘Oh, really, did you see all that that we saw in [Saving] Private Ryan?’ ‘I killed 18 people in three days.’ ‘You didn’t! How dare you say a thing like that! You never killed anybody!’ I say, ‘Darling, how do you think we made the world safe for all you little people from 1939 through 1946? If we didn’t kill people.’ ”

Discharged in 1947, Macnee returned to the theater and raised a family (a son and daughter) and also obtained small roles in films, among them Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948). In search of work, he went to Canada where he built a reputation on television (he appeared in a live American TV version of A Night to Remember in 1956).

He had trouble finding jobs, however, and eventually took an associate producer position in England on The Valiant Years, a documentary series, based on Winston Churchill’s memoirs. When the producer of that program was suddenly fired, Macnee took over. It was then that Sydney Newman called. The TV producer had worked with Macnee in the past. And when he was preparing The Avengers, he thought of the actor for the Steed role. It was a “George Sanders type” who was supposed to be slightly mysterious, slightly shady, and very elegant. (The producer even wanted Macnee to wear a Sanders-like moustache; but the actor refused.)

Macnee agreed to co-star. Yet for a series that would become known for its light-hearted approach to murder, the first season of The Avengers was certainly gritty and hard-hitting. “Hot Snow,” the initial episode, was dark, realistic, and, because it was shot on videotape and live-on-camera, very stagy. Its subject matter was most unAvengers-like, dealing with drug-smugglers (a hot button issue), bereavement, and the seedy underside of British crime.

When Macnee’s first partner, Ian Hendry, left the series after 26 episodes, producer Leonard White wanted Honor Blackman for the part. But White faced complaints from Newman and others who felt that Blackman was completely unsuitable, since, until then, she had played vapid wives and a variety of other colorless characters. Newman argued that Blackman was saccharine and too genteel for the role. He wanted Nyree Dawn Porter.

“It is true that being a natural blonde – my very first cutting in any newspaper says, ‘A peaches and cream complexion,’ and all that kind of stuff – I was very typically British, which implied, I’m afraid in those days, not spunky,” Blackman recalls. “So, yes, probably it was a surprise [when they chose me].”

Honor Blackman.

The character Blackman would ultimately play in The Avengers was named Cathy Gale and was modeled on a number of women who had inspired Newman: the anthropologist Margaret Mead, Margaret Bourke-White, a well-known Life magazine photographer who took on dangerous assignments; his own wife; and a woman he had heard about in Kenya. According to Macnee, at the time of the Mau Mau insurrection in Kenya, Newman had “read of a redoubtable lady whose farm had been besieged by native insurgents.”

Because of his background, Macnee found it easy to get along with Blackman. “I never thought about it,” the actor says. “But growing up, all I knew were women. So...it didn’t phase me at all. I asked Honor Blackman when she went and played with Sean Connery in the Bond film [Goldfinger], she said, ‘Oh, he wouldn’t let me get away with a thing.’ Implying that I left her get away with almost everything, which I did.”

The actor recalls that he refused to lift any traits from the literary James Bond in his creation of Steed. “We were before the Bond films,” he notes. “Somebody gave me a Bond book [at the time the series began] and said, ‘I think this will help you with your character.’ I read it and found it, as I always have, totally repulsive. Bond is a repulsive man. A sadist. He’s completely upper-class, frightfully snobbish. He’s exactly like Ian Fleming was. Ian died of drink and tobacco just like that, way before his time.No, Bond is totally reprehensible to me.”

Steed was instead crafted as a parody of an English gentleman, but one who treated women as equals. His relationship with his partner was defined early on as one of mutual respect, tempered by Mrs. Gale’s dislike of Steed’s unscrupulous methods. She was the “know-it-all” to whom Steed came for assistance; he was the man with the mission. “To me the great secret of The Avengers is the knowledge that woman can not only keep it going with men. but can top men, and can rescue men and they can treat men as their friend and equal without emasculating them,” Macnee says. “There’s too much made of male-masculine thing, I think. ”

The live-on-videotape aspect of the series added to the excitement of the show’s early years. “The point is live television is live television,” Macnee says. “I did that in New York in the ‘50s and you’re not at your best, let’s face it. You’re sort of tentative, you’re nervous...When you have to do a series like The Avengers which, for four years was live [on tape], you really had to be on your toes. And I think if you’re on your toes, your brain works better, and I think what I did show in that show for all those years was a brain and [that I was] a sort of alert person.”

“There were no retakes,” Blackman adds. “If somebody died in front of the camera, you stepped over them and took their lines. It really was a nightmare. I must say, that was one thing about Patrick. Sometimes, he used to wing it. And he would always, miraculously, get back to your cue. It was quite extraordinary. You’d think, ‘Now where’s he gone now? Will I ever be able to answer the sentences made?’ And then he’d always come back to his cue. He was quite amazing like that.I’m a very solid performer. I like to know what I’m doing. And certainly if you’re working with someone like Patrick who flies occasionally, it’s as well that one of us is the substantial person.”

Blackman dropped a bombshell in 1964, when she announced that she was leaving the series to take on the part of Pussy Galore in the third James Bond film, Goldfinger. As he had when Hendry left, Macnee thought that it would mean the end of the series. Although many felt that Steed was the backbone of the show, Mrs. Gale seemed to be its main draw.

After a much-ballyhooed search, Blackman was replaced with Diana Rigg. The new character was originally called Samantha, but later renamed Emma Peel (a play on the words male appeal: “m-appeal”). Like Mrs. Gale, the character was a widow. Macnee and many critics feel that the black-and-white Macnee-Rigg season of 1965-66 was The Avengers at its best. The series took on an even more outrageous tone and was more tongue-in-cheek than ever. It also became more sophisticated and stylized, which was now possible because of a switch from videotape (and the slightly stilted, live-on-tape presentation) to film. (The conversion was made as a way to sell the series to the important American market). Film allowed for higher production values, more outrageous plotting, and higher caliber directors.

Linda Thorson.

By 1966, The Avengers had a worldwide audience of over 30 million viewers in 40 countries. Between 1961 and 1969, it spent a total of 123 as one of the top 20 series in Britain, and in 1967, its peak year, it was the third most-watched program of the year, on the top ten chart for 23 weeks. And that success continued, unabated, into the 1990s, when the series was called the most profitable British export of all time.

Macnee is not modest about his contributions to that success. “The wit in me is me,” Macnee says, “and [from the series’ chief writer and producer] Brian Clemens. I like to think I’m wittier than him and he does the plots. So the wit is me. The attitude is me.”

Macnee continued in the role following Rigg’s departure in 1967, and co-starred with the 20-year-old Linda Thorson for 30 episodes before hanging up his bowler hat in 1969. He then appeared in various forgettable films, and, more memorably, for two years in Anthony Schaeffer’s Broadway play, Sleuth, starting in 1974. In 1976, he returned to the part of Steed in a 22-episode revival called The New Avengers, opposite Joanna Lumley (pre-Absolutely Fabulous) and Gareth Hunt. “I was not too fond [of that series] because it was badly thought out and it wasn’t ahead of its time, it was behind its time. And I don’t like that,” he says. “I was in the first motor torpedo boat flotilla in the war, not the second.”

Even though he expressed antipathy towards James Bond, he later followed in the footsteps of Honor Blackman (Goldfinger) and Diana Rigg (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service) and took a part in 1985’s A View to a Kill. “I was doing a Magnum PI, which I enjoyed very much...and Barbara Broccoli – who is now the producer of the Bond films [and Bond producer] Cubby Broccoli’s daughter – had a boyfriend on it, and she saw me work on this thing and apparently she went to Cubby Broccoli and said, ‘What about Pat Macnee for the part of’ – it was a jockey at that time, ‘in A View to a Kill?’ And he said, ‘I think he’s a bit big for a jockey.’ And they rewrote it. I just read a thing called The Bond Dossier, which gives me a wonderful write-up which said, ‘If only the character had gone on longer, he would have been a good partner for James Bond.’ Which was a nice thing to say.”

He adds: “The cameramen, all the technicians, they were all people, strangely enough, who had worked on The Avengers. And Roger Moore is an old friend; we were in Hollywood together in the early ‘50s. So we have known each other, all those sorts of people, for years and years and years. So you play the thing with confidence. It’s just like [on] that Bond film, I treated it as though it were another Avengers.”

He appeared in a two-part episode of Battlestar Galactica as The Devil, co-starred in a failed adventure series, Gavilan (1982-83), and a failed comedy program, Empire (1984), and then had various guest shots on a wide range of American TV series, most recently on Diagnosis Murder, with Dick Van Dyke. He played a spymaster involved with former TV spies Robert Vaughn (The Man from U.N.C.L.E.), Barbara Bain (Mission: Impossible), and Robert Culp (I Spy). “It was so sweet,” he recalls. “Dick Van Dyke, said, ‘You know, Patrick, I’m so glad you’re in this thing because, up until now, the last two years, I’ve always been the oldest person.’ What a lovely man.”

He also cameoed – voice only – as an invisible spy in the big-screen version of The Avengers in 1998. He doesn’t mince words about that movie. “The Avengers is a little television show and that’s what it is. And a very good television show. But it never should be a movie. The movie’s proved it. I felt so sorry for Ralph Fiennes [who played Steed] because I read that script and it was rather good. And, do you know, the producer, [Sy] Wyntraub, he insisted that the woman be dominant. Of course, that ruins that show altogether. So consequently all the scenes that they had done together, they cut all of Ralph Fiennes’ stuff out.

“Howard Rosenberg gave a lovely contrast between that film and The Avengers television,” he continues. “There’s a sword fight – Uma Thurman [as Mrs. Peel] and Fiennes have a sword fight – and I and Diana Rigg had a sword fight [in the TV series episode, “The Town of No Return”]. At the end of the one with Uma Thurman, Uma Thurman wins. Now in the other one, I win, and then she, Diana Rigg, comes out from behind the curtain, and says, ‘You cheated.’ And I say, ‘Well, I never said I’d fight fair.’ Now, that’s The Avengers.”

New Avengers reunited, 1998: Joanna Lumley, Patrick Macnee, Gareth Hunt.

New Avengers reunited, 1998: Joanna Lumley, Patrick Macnee, Gareth Hunt.

Still, his last piece of television acting was a far cry from The Avengers: a series starring Hulk Hogan. “I can’t remember the bloody name, we did it in the desert, in the Disney World in Florida, and it was with Hulk Hogan, and it was marvelous. It was about a ship, a boat, and I played a very good part in that, only a couple of years ago, made by the people who make Baywatch.”

Surprisingly, Macnee – who had frequently been voted best-dressed man of the year in the 1960s – also spent time in a nudist colony. “Somebody asked me [about that] on a talk show, and, by mistake I timed it very well. I said, ‘Yes, indeed, I was in a nudist colony’ – and the next line, if you time it right, can get the laugh – ‘but, you know, I love to play tennis. But I’m unable to serve with two balls in my hand. I have no clothes on. I have nowhere to put the two balls.’ ...The truth of it is, was I was in it for a time because I wanted to see what everyone else looked like with no clothes on. Because if you’ve lived a life completely clothed, it’s rather fun to see people stark naked, particularly attractive people. Now I, quite frankly, wanted to go to, having lived with lesbians, and done this and been in a very overdramatized sort of life and been in the war, I wanted to just see this nice sort of simplicity of nudity. Yes, I enjoyed it very much.”

He adds: “People are idiots because they can’t face a truth. Undo a bandage and there are six stitches underneath. It’s not three, six. We’ve got to face little truths. We’ve got to see cancer where it is. We’ve got to try and do something about things by facing it.”

The actor is blunt about his own talents. “I was no great Shakespearean actor. I can admire Ian Holm, the shortest King Lear. I can admire Sir Anthony Hopkins, who is superb. I can admire all of these, but they’re not role models...They wanted me to understudy Paul Scofeld. Let’s say the greatest actor who ever lived, who’s still alive is Paul Scofeld, in my opinion...they’re great, great stage actors. Acting is, probably – all in all, you have so much practice, you can’t go to a television studio every day and do Seinfeld and not learn something, can you? You bloody well ought to be good...”