Fess Parker

MY BREAKFAST WITH FESS

By TOM SOTER

Fan meets the man: Fess Parker, with TS, 1998

It all started with a phone call. Every summer, from 1992 until 1998, I had been traveling to San Francisco to visit my older brother, Nick, and his family. Every year, before I came out, he would ask me, “What would you like to do when you come here?” And every year, invariably, I would say, “I don’t know. Hang out, relax, read.” As you can see, I wasn’t a big vacation planner. But this year, 1998, I had an idea. “Why don’t we go to the Fess Parker winery?'

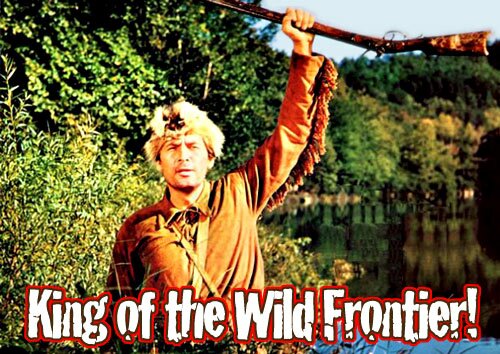

Now, Fess Parker, as baby-boomers of the 1950s know, was Davy Crockett, an American frontiersman who famously died defending Texas at the Alamo and who was immortalized in the song, “Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier.” That tune was sung in the Walt Disney mini-series (there were only five episodes), Davy Crockett.

And baby-boomers of the 1960s, like me, knew him as Daniel Boone, who may not have been king of the wild frontier but was pretty remarkable nonetheless (as his theme song explained, he had “an eye like an eagle” and he was "as tall as a mountain”). In my youth, I had been obsessed with Dan’l. (On the show, everyone called him that, except for his wife, Becky – she called him Dan – and his two friends, the Oxford-educated, part-Cherokee Indian Mingo, and the runaway slave Gabe Cooper, who both called him Daniel.) I had a hat reportedly made from a raccoon (a coonskin cap), I had a buckskin jacket with fringes, and I even owned an imitation musket (the single-shot rifle used by men like Boone). I also kept checking out my high school library’s copy of the biography Daniel Boone: The Opening of the Wilderness every week (when they retired the library card they gave it to me). And I would often go to sleep listening to audiotapes I had made of the theme song to the Daniel Boone TV series (“Daniel Boone was a man, yes a big man....”)

Daniel Boone toy fort, 1964.

Even though it was a long drive – Parker’s winery was closer to Los Angeles than San Francisco – my brother agreed to the idea of visiting the winery. But it was his wife, Dora, always practical, who came up with the killer idea: “As long as you’re there, why don’t you try and set up an interview with Parker?” As my brother added: “Yeah, as long as you’re traveling all that distance, you might as well get something besides a coonskin cap!”

As a freelance writer, I had met and interviewed many celebrities in the past, including some who were childhood icons – Patrick McGoohan, Raymond Burr – but Fess Parker was at the top of my list (perhaps sharing the space with McGoohan). I figured one of my clients (such as Entertainment Weekly or Diversion) would jump at the chance to run a piece on Parker, so I called up the winery and arranged an interview with the great man (it was surprisingly simple). The drive was uneventful. We stayed in Parker’s hotel complex (he had just bought the Grand Hotel chain) and drank his wine, which my brother, often critical of food and drink, found remarkably good. We bought some bottles of wine, calling them “bottles of Fess.” It was all delightful.

My appointment was for breakfast, the next morning. I arrived, nervous and excited, to find him sitting with an assistant, a pleasant young man, at a table on the porch. He was tall (over six feet), white-haired, and slightly jowled, but he was still recognizably the "big man with an eye like an eagle" who "rassled alligators" and wowed a nation as a overnight sensation in 1955 as "the king of the wild frontier." Not surprisingly, he eschewed buckskins – “too hot,” I thought to myself – and was dressed in a short-sleeved blue polo shirt (imprinted with the logo “Fess Parker Winery”) and slacks. He smiled that affably crooked grin that I knew so well from countless Thursday nights of Daniel Boone-watching as he stood up to shake my hand. We sat on the front porch, and as we talked, he leaned forward occasionally to make a point. He gave detailed answers on any subject he was asked about, but when he finished speaking, he came to a full stop and politely waited for the next question.

Parker as Crockett: baby boomers knew his song

Parker as Crockett: baby boomers knew his song

We initially talked a bit about the winery – he was very proud of it. How had it all started? Realizing that he was typecast as a television frontiersman, he explained, he began exploring other business frontiers. In the 1970s, he invested his money in hotels and was now running a phenomenally successful chain of Fess Parker Hotels. Then, in 1987, he purchased 714 acres of ranch land in Los Olivos, California, which became the home of his vineyards, winery, and families (he had a son, daughter, and grandchildren).

The family enterprise released its first wine in 1989. In 1998, the Parkers had 25 employees and 65 acres of vineyards plus another 85 acres in Santa Maria, California, with 25 more acres to be planted that year. The Parkers put a lot of effort into creating a destination where people would come and linger. The 9,600-square foot winery building, which was completed in 1994 in a handsome English colonial style, had a rambling veranda that was immensely popular with visitors. Parker chose the architectural design himself after seeing similar architecture in Australia on a 1985 visit to represent the president of the United States at the Coral Sea Celebration. The winery wasn’t an instant success, recalled Parker, who acknowledged that he had to deal with people’s preconceptions. In 1994, for instance, a wine writer from San Francisco was in the area but he did not visit the winery. Parker’s publicist sent him a couple of bottles of wine.

“In a subsequent column, he wrote that he had been in our area and he’d driven past our winery and he had thought, ‘What does an old television actor know about making fine wine?’” Parker said. “And so he just passed on. He wrote that ‘mysteriously’ a couple of bottles of wine appeared on his desk and that he had an opportunity to try them and he wrote that ‘they went extremely well with crow.’” The Fess Parker Winery business continued to grow. Parker worked with IBM to establish an operation to sell his wine via the internet. The winery was now receiving sales orders and wine club memberships and directly hosted the rapidly-growing Fess Parker Wine Club. In six years, annual wine production increased from 4,000 cases to 35,000 cases marketed nationally.

We talked more about the winery and then, finally got down to what were, for me, the real deal: his early life, movies, TV, and Davy and Dan’l. An only child, Parker was born in San Angelo, Texas, on August 16, 1924. “When I was six years old, my father sent me to his father’s farm and then I would spend two or three weeks there and then I’d go and spend two or three weeks with my grandmother on her Hereford cattle ranch. So, that was my life for the next 10 years; every summer I went to the farm and ranch and lived with my grandparents.” There were no children around, which, he said, “was both good and bad; I lived in an adult world and so it assisted me in certain respects. But I was a movie fan, I loved the Flash Gordon serials. And then I grew through the era of the big musicals and into the time where [director] John Ford and [actors] Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda and all those people began to make an impression on me. I have no idea why I decided I wanted to be an actor, but I just did.”

We talked more about the winery and then, finally got down to what were, for me, the real deal: his early life, movies, TV, and Davy and Dan’l. An only child, Parker was born in San Angelo, Texas, on August 16, 1924. “When I was six years old, my father sent me to his father’s farm and then I would spend two or three weeks there and then I’d go and spend two or three weeks with my grandmother on her Hereford cattle ranch. So, that was my life for the next 10 years; every summer I went to the farm and ranch and lived with my grandparents.” There were no children around, which, he said, “was both good and bad; I lived in an adult world and so it assisted me in certain respects. But I was a movie fan, I loved the Flash Gordon serials. And then I grew through the era of the big musicals and into the time where [director] John Ford and [actors] Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda and all those people began to make an impression on me. I have no idea why I decided I wanted to be an actor, but I just did.”

As a senior at the University of Texas, he met the veteran film star Adolph Menjou, who was a friend of one of Parker’s professors. “I was taking Russian as my undergraduate language and Menjou came to the Texas campus to narrate Peter and the Wolf. He was also to lecture about his experiences in Hollywood. They had 8,000 people come to hear that. I had a little car, and my professor didn’t have a car so he sent me down to the railway station to pick Menjou up.”

Menjou and the professor had time to kill, “so I drove them around [on a tour] and then took him to my fraternity house and we had lunch there. Then I had a little party after Menjou’s performance for a few friends and the next morning when I took him to the station, he said, ‘Would you be interested in working in films, in westerns?’ And I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’ He said, ‘Well, you send me some 8 x 10s. I’m going to do a picture with Clark Gable called Across the Wide Missouri with [director] Bill Wellman, he’s a good friend of mine.’ So that was all the confirmation that I needed that it was a rational idea. Not that anybody else believed it was rational.”

Parker as Crockett: Disney kept him from John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe.

That was in 1949 and, for the next six years, Parker struggled to succeed in his chosen profession. Luck finally dealt him a card. Walt Disney was looking for an actor to play Davy Crockett in a TV series. Someone suggested James Arness, pre-Gunsmoke, who was then starring in a sci-fi thriller called Them! Disney screened the movie and was more impressed by Parker, who had a five-minute role as a man who had been terrorized by a giant flying ant. Parker was signed to a seven-year contract.

“I was thrilled to have Walt Disney as a producer,” Parker noted. “He put me under a personal contract. I thought that was wonderful.” When the three-part Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier aired on Disney's Disneyland series (as the first true mini-series), no one expected the deluge: millions of children sang the No. 1 theme song ("Davy, Davy Crockett, king of the wild frontier"), store owners frantically stocked their shelves with coonskin caps and toy muskets, critics and historians heatedly debated the accuracy of the Crockett depiction in magazines, newspapers, and radio shows, and schools were renamed in honor of the man who died at the Alamo. Surprisingly, the long-dead Crockett was even elected to a local political office as a write-in candidate.

Davy Crockett comic book.

“I think in hindsight it’s a miracle that someone didn’t put two and two together and say that when Walt Disney produced a television series for the first time that more than likely the world would pay attention.” He added: “It was so intense, it was amazing. [The 'Ballad of Davy Crockett'] was number one on the Hit Parade for four months.”

Parker was catapulted to instant fame but for the star, it was a mixed blessing. As an actor, he wanted to grow. As a performer, he relished the limelight. Things didn’t turn sour for him, however, until he renegotiated his contract with Disney, Now a star, he wanted a star’s salary. Disney, of course, felt he had made Parker and had a Svengali-style interest in – and an exclusive contract to guide – his young star’s career. Disney was, Parker recalled to me, a “great guy, liked him a lot. He was somebody I understood; he was from a small town, but a brilliant man.”

Daniel Boone comic book.

Parker expressed mixed feeling about that time, about the might-have-beens. “It’s kind of a strange thing. I had two opportunities to have a broader career; I don’t know if I would have maximized them but I didn’t get the chance. One was John Ford wanted me to do The Searchers with John Wayne and Walt Disney wouldn’t let me do that. In fact, I didn’t even know it until it was already done. Jeffrey Hunter was my co-star in The Great Locomotive Chase and we were driving from Atlanta to the location and Jeff was sitting next to the driver and Walt and I were in the back seat and Jeff, just making conversation, said, ‘I just had the best experience of my life.’ 'What’s that?' And he said, ‘Doing a picture with John Ford called The Searchers.’ Walt turned to me and said, ‘They wanted you for that.’ That was the first time I’d ever heard of it. Then, later, when Marilyn Monroe was going to do Bus Stop, I knew about that play and I took it over to Walt’s office and said, ‘I’d like to play this part.’ And he read it and wrote me back an inter-office memo that said, ‘From Walt to Fess, I don’t think this is the kind of part you should do, Walt.’” Parker was disillusioned and became more so when Disney turned distant after the salary renegotiation. A notorious tightwad, who saw his actors as his “children,” Disney was presumably hurt by Parker’s attitude.

Parker and Patricia Blair on Daniel Boone.

“There was a point where two or three studios wanted to share my contract with Walt and he said no, and then in the end, after I was a couple of years into my deal, Ray Stark became my agent. He asked for a raise and got me a substantial raise, but Walt didn’t want to pay that, so he put me under contract to the studio [and gave up personal management of me]. And there was absolutely no idea what to do with me there so they started giving me featured parts.”

That meant small roles in pictures like Old Yeller, where a dog and his boy were the true stars. Finally, Parker was offered a role that was essentially a voiceover. “I had about five pages. So, I wrote to Walt and I said, ‘You know, I can’t do this.’ ‘Why not?’ I said, ‘Well, are you going to [bill me as a] co-star in this picture?’ ‘Yes.’ I said, ‘Well, I haven’t any part, I think it’s dishonest.’ And I said, ‘I can’t just go backwards like this.’ Well, he disagreed, he didn’t take that stand and he got Bill Anderson who was his VP and hatchet man, to take over [talks with me] and I just said, ‘I’m not going to do it.’ And with that – they were unhappy and I was unhappy – we cancelled the last five years of my contract.”

Since Parker considered Disney a father figure and mentor, the move “really was a cataclysmic thing for me, emotionally. I’d found a home, I’d found a father figure and then I had to do that. I learned a long time ago that here are just things you have to do, you can’t… If you don’t do them then you’re sunk-you just lose your confidence and you have to do it. So, I left the studio and a few weeks later I was under contract to Paramount and that was fine.”

Parker paused. He was very forthright and straightforward, with a folksy, familiar manner of telling stories. I found him easy to engage, and he apparently felt the same way about me, at one point noting, “I’m enjoying talking with you.” We both ate blueberry pancakes. He occasionally took calls in a little cell phone, which seemed tiny in his huge hands.

He talked, briefly about his post-Davy film career – and briefly was the best way to talk about it. He appeared in television (on Death Valley Days and General Electric Theater) and as Sheriff Buck Weston in the movie, The Hangman (1959); then he had a small part in the Steve McQueen war film, Hell Is for Heroes (1962).

In 1962, he inherited the James Stewart movie role in a TV version of Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, a one-season sitcom that he remembered vaguely. Then, NBC approached him about doing a TV series about Davy Crockett. “Walt had The Wonderful World of Disney on Sunday nights on NBC, so he said, ‘No, I don’t want to do that. Yeah, I think I’ve got these five hours of Davy Crockett and I don’t want to dilute them.’ So, he actually stopped it until somebody said, ‘Well, why don’t we do Daniel Boone?’ Which presented me with a little bit of a problem; I was already typecast as Davy Crockett for 10 years, now all of a sudden I’m going to put on a cap and say, ‘My name’s Daniel Boone and I live in Kentucky and I have a different wife and different children’?”

He wasn’t thrilled about the prospect but went along for practical reasons: “By this time, I had a family and I thought maybe this would be a security. Anybody that’s interested in the entertainment business has to have an unlimited capacity for insecurity. You just live in a dream world and sometimes the dreams come true and they’re not really the dream that you’re dreaming, it’s another dream that other people dream that you would want. But it isn’t necessarily what you want. I think if you really want to be an actor, you want to grow, you want the opportunity to have a satisfactory career, not one dimensional. And there are a lot of things that are so subjective. I mean, I’m 6 foot 6, I don’t necessarily fit in a normal milieu, if you will. People like Gregory Peck who are maybe like 6-2½, or 6-3, that’s fine. But [if] you just tower over people, it doesn’t work. I had a lot of reasons why the opportunities never came.” “Actually,” I said, thinking he was apologizing for Daniel Boone, “I think it’s superior to Davy Crockett as a series.”

TV Guide story on Fess Parker and his real estate deals, 1968.

TV Guide story on Fess Parker and his real estate deals, 1968.

“In a lot of ways,” he admitted. “I had a lot of good people. The first year was hell; we had several producers. We did 30 hours in the first year, in black and white and that was a double cross. I just made a condition doing the show that it would be in color. Well, I was already signed up, I’d made a commitment, and then they didn’t back me. [In addition,] it turned out that a lot of these people didn’t have any idea about the historical background of Daniel Boone and didn’t care much. So, I was rewriting on the set. And then that continued because the next year we had, I guess, multiple producers before a director, George Sherman, took over and got us through the end of the season.” But, he added: “I loved the ensemble effort of the cast and crew. We had the same crew for six years.”

Parker’s rewriting of the scripts was not generally known. “I was an American History major, got my degree in that at the University of Texas,” he noted. “I’d read a lot about Daniel Boone.”

Nonetheless, both the Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone series were filled with inaccuracies (starting with the fact that neither Davy nor Daniel wore coonskin caps). Boone, for instance, was not a “big man” in a physical sense: unlike the 6-foot, 6-inch Parker, the real Daniel was an ”average man,” coming in at 5-9 or so. And he was no slavery-hating liberal; like any good southern landowner, he had his share of slaves. He was also apparently more sexually active than his television counterpart: compared to TV Dan’s two kids, Israel and Jemima, real Dan had at least a dozen children Of course, he had no Oxford-educated Indian friend named Mingo, but one aspect of that relationship carried some truth: he frequently befriended native Americans, lived for nearly a year with the Shawnee Indians as the chief’s adopted son, and learned much of his backwoods skill from his dealings with native Americans.

The real Daniel Boone: no coonskin cap.

Daniel Boone generated much less heat than Davy Crockett but was a solid breadwinner over 165 episodes broadcast between 1964 and 1970 (it appeared in the 20 most-watched TV programs in 1968 and regularly beat its competition). Parker thought it could have run even longer, however, “but outside situations intervened. Twentieth Century Fox [the show’s producer] had lost an enormous amount of money with Cleopatra and they were selling off the back lot of the studio and so they needed money. So they took the show off the air and put it in syndication [even though] we had put away the Donna Reed Show and we put away the Red Skeleton Show, we put away Batman. And Cimarron Strip had gone bye bye. In 1968, we were in the top 20.”

NBC publicity magazine,1964.

But the series disappeared from syndication because Parker sued the studio over profits. “I had 40 percent of the net profits and was under the impression that I had a negotiated a reasonable contract as owner and co-producer. I was informed that there would never be any profits even though for five of the six years we had brought the show in under budget so there was money that could be anticipated. I was seven years in the lawsuit. But we did settle it.”

He got into real estate in the mid-1970s, after making a TV-movie (Climb an Angry Mountain) and turning down the role that Dennis Weaver made famous of cowboy-turned-big-city-detective Sam McCloud (“I didn’t want to do another series”). “In ’58, I actually bought a home and started coming to Santa Barbara and thinking of it as my place,” he said, explaining how he had turned to real estate. “But in ’60, I was married and I began to look at property. One of my friends was a contractor and so we built the mobile home park and that was sort of the beginning. Pretty soon, [because of real estate development,] I was independent of any financial [worries]. I found, much to my surprise, I felt a greater satisfaction and creativity in looking at real property. I think my strongest suit in real estate is not in execution so much as it is in concept and what you can do with something that’s unrealized.”

Daniel Boone viewfinder packaging, 1967.

Daniel Boone viewfinder packaging, 1967.

He was soon developing a successful hotel chain. “I had never thought about putting a hotel deal together, but it’s sort of a Texas trait—I was talking with some friends about it the other night—there’s some sort of cultural thing in the Texas makeup, you know? Here’s a hotel that needs to be built, you don’t necessarily have to know a lot about it, just do it, you know? Just start. And so that’s what I did. I mean, I ended up with 32½ acres of downtown Santa Barbara waterfront and what the city wanted was a hotel conference center. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll build it.’ Didn’t have the slightest clue how I was going to do it and it was a very unusual, complicated way that I worked it out, but I did and I’ve got one more to build.”

We talked about the winery again, touched on politics (a Republican, Parker had thought of running for the Senate in 1985 but abandoned the idea), and then I asked him how he thought he stood when compared to the real-life Boone or Crockett.

“I would come up way short,” he said quietly. “I’ve benefited from the adulation of people who enjoyed the shows but you know, people are just people and the experience causes you to be more conservative.”

“The experience of?”

“Being a public figure.”

“You mean more conservative in what you do because you feel you’re in the public eye?”

“Well, that and there’s a responsibility attendant to it. It’s a subtext; I do the best I can and I’m sure Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone in their lives did the best they could. And we look at them through this particular set of lenses because we’ve taken their lives into so-called entertainment. But the reality of their lives could be, as some people insist, quite different.

“Well, that and there’s a responsibility attendant to it. It’s a subtext; I do the best I can and I’m sure Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone in their lives did the best they could. And we look at them through this particular set of lenses because we’ve taken their lives into so-called entertainment. But the reality of their lives could be, as some people insist, quite different.

“It’s a strange thing, you know? Everybody thinks their world is the world and as a matter of fact, you know, it isn’t, but you can live with that illusion that your world is the world and it’s the most important world and that everybody’s paying attention to it. That’s the way actors tend to think. And then you find out, well, really, you’re in a comic strip. You’re not taken seriously as an individual, you are suspect because you’re part of that industry. What kind of work is that? What is that to somebody who’s doing some pretty heavy-duty labor, however you do it? You take an actor and you say, ‘Well, you can’t act anymore,’ what the hell do you do? I mean maybe you can sell real estate; some have, beautifully, very successfully or do something else; you name it. At the very least, they’re a resourceful kind of group if they’re not somehow or other incapacitated by their ego. I grew up out on the farm and ranch if something didn’t work you’d get a piece of baling wire and maybe tie it back together and then it’d work, you know? You find a way.”

And so the interview ended. He signed a photograph for me, posed for pictures, and I never saw or heard from him again.

I thought of all this the other day, when I heard the news that Parker, 85, had died. I remembered my interview with him and a story my father had often told about my youthful obsession with Parker’s Boone, the man who tamed Kentucky. When I was 10 or 11, I complained to my father about our family’s annual summer trips to Greece. Oblivious to the beautiful sun and sand, I longed for a different kind of setting, one that existed (although I didn’t know it at the time) only on a Hollywood soundstage. “Greece again?” I would sigh, jaded world traveler that I was. “Why do we always have to go to Greece? Why can’t we go to Kentucky?”

Now Parker was gone, but for one brief moment, I had met Daniel Boone. I had gone not to the real Kentucky but to the never-never land of my dreams. I had met Dan’l and not found him wanting.

“Thank you for a pleasant visit!” he wrote on the picture he autographed. No, thank you, Fess. You really were a big man.

April 12, 2010

All memorabilia from Tom Soter's private collection.