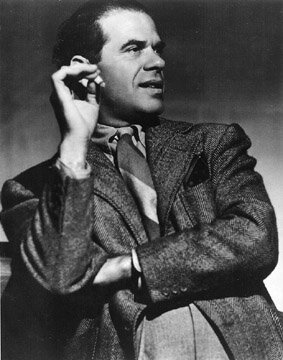

You are hereMagazines 2000-2009 / Frank Capra

Frank Capra

IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE

The Films of Frank Capra

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 2000

Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night. The thin young man seems battered, worn down. His tie is askew and his chin unshaven, but there is a passionate gleam in his exhausted eyes as he begins to speak haltingly, with a rasp in his voice.

Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in It Happened One Night. The thin young man seems battered, worn down. His tie is askew and his chin unshaven, but there is a passionate gleam in his exhausted eyes as he begins to speak haltingly, with a rasp in his voice.

“I guess this is just another lost cause, Mr. Paine,” he says to an older man sitting in front of him, one of dozens of senators who are watching this young speaker as he addresses the U.S. Senate. “All you people don’t know about lost causes. Mr. Paine does. He said once they were the only causes worth fighting for.” He pauses. “And he fought for them once. For the only reason any man ever fights for them. Because of just one, plain simple rule. ‘Love Thy Neighbor.’ And in this world today, full of hatred, a man who knows that rule has a great trust...”

His raspy voice is rising with passion and urgency. “And you know that you fight for the lost causes harder than for any others.” He pauses. “Yes, you even die for them.” He turns to face the crowd. “You think I’m licked. You all think I’m licked. I’m not licked. And I’m going to stay right here and fight for this lost cause...Somebody’ll believe in me!”

The climactic speech by Jimmy Stewart in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) is pure Frank Capra: a combination of uncompromising ideals and relentless sentimentality. It is stirring, passionate, melodramatic, touching – “Capracorn” to some, but effective nonetheless. And although the director died five years ago, Frank Capra’s films and his influence seem to be going stronger every day.

To celebrate the centennial of the filmmaker’s birth, Columbia-TriStar Home Video has released a collection of 10 Capra classics, including the documentary, Frank Capra’s American Dream (1996) and the rarely seen Miracle Woman (1931) and Platinum Blonde (1932); the University of California Press has issued Six Screenplays By Robert Riskin (from Capra-directed movies); and the NBC television network is once again airing what has become a Christmas perennial: the soberly sentimental It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Capra’s ode to friendship.

Capra’s “touch” can be seen in modern films, as well, with critics coining the phrase “Capraesque” to describe anything that is either corny or inspirational (or both) that involves the common man rising up to back an underdog. The recent Kevin Kline comedy In and Out, for example, has a heartwarming ending that could easily have been lifted from Capra in which the population of a small town stands up to (falsely) declare its communal homosexuality in support of a gay teacher.

Surprisingly, the quintessentially American director was born in Bisaquino, Sicily. The sixth of seven children, Frank came to California with his family when he was six. After a farming accident killed his father, the youth put himself through high school and then college by working in factories and in newspaper plant. He graduated from Cal Tech with a chemical engineering degree.

After World War I, Frank spent three years drifting between jobs before he directed his first movie in 1921. He became a film editor and then a gag writer, and soon was directing silent star Harry Langdon in two of his biggest hits. A falling out with Langdon temporarily derailed the director, but he eventually signed up with Columbia Pictures, dubbed “Poverty Row” because of its low-budget efforts.

An act of desperation by the struggling Capra – who had aspired to work for the more prestigious MGM – the partnership soon became a marriage of salvation for both Capra and Columbia. Within five years of signing on, the director’s movies were generally Columbia’s biggest money-makers, as well its most critically acclaimed hits. He did everything from mysteries (The Donovan Affair, 1929) and action flicks (Dirigible, 1930) to women’s “weepers” (The Bitter Tea of General Yen, 1932) before he found his groove with screenwriter Robert Riskin.

Riskin gave Capra a focus and the two of them collaborated, in one way or another, on over a dozen movies. “We vibrated to the same tuning fork,” Capra once said of his partner. Added an observer who knew them both: “Frank provided the schmaltz and Bob provided the acid. It was an unbeatable combination. What they had together was better than what either of them had separately.”

The Capra-Riskin formula usually involved a number of elements: naturalistic performances, superb supporting characters, a hearty serving of sentiment and good horse sense, witty dialogue, and a basic plot in which a Christ-like innocent goes up against an entrenched system that nearly destroys him. The protagonist, becoming wiser in the ways of the world, would escape defeat by the love of a woman and the help of the little people. In the process, his virtue is redeemed and deepened by the experience. As the novelist Graham Greene put it, the director’s favorite theme was “goodness and simplicity manhandled in a deeply selfish and brutal world.”  Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Capra used the techniques of film – lighting, cutting, actor’s expressions – terrifically well. “[There are] moments or scenes that descriptions of the characters or summaries of the plot of the movie leave out,” wrote Ray Carney in American Vision: The Films of Frank Capra. “They are scenes or fleeting moments within scenes in which perhaps nothing is happening socially – moments, for instance, when characters simply sit still and are silent; when they look at each other but do not speak; when music swells on the soundtrack, or the rhythm of the editing changes, or a special lighting effect is employed, even though nothing is apparently happening in terms of the advancement of the plot or the dialogue spoken. Such moments, when the social situations of the characters or the lines they speak cease to express the meaning of a scene, are frequently the most important ones in Capra’s movies.”

Through such films as Lady for a Day (1933), It Happened One Night (1934), and You Can’t Take It With You (1938), Capra became known as a proponent of the common man, downtrodden in real life by the Depression. But, as Joseph McBride points out in Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, the irony is that Capra himself was a conservative Republican and fan of the dictator Mussolini, who voted against Franklin Roosevelt four times because he was afraid the Democrat would redistribute the director’s wealth, much as his own Mr. Deeds wants to do at the end of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936).

“Like the popular artist he was, Capra was being led by his audience,” observed McBride. “They were demanding reform, they were demanding social welfare programs and redistribution of wealth, they were angry at the shortsightedness and greed of big business and the Republican party. The sense of brotherhood and compassion that came from Riskin’s writing and began to open up the narrow vision of Capra’s work brought him into closer contact with his audience, giving his work a deeper and more popular resonance, putting him in touch with a sense of community for which he previously had little feeling.”

Capra was also successful because he had the savvy and good sense to partner with collaborators who would increase his strengths as a cinematic storyteller, from cameraman Joseph Walker’s sophisticated lighting techniques to screenwriter Riskin’s clever characters, construction, and dialogue. “Capra in the prime of his career liked to surround himself with colleagues who were not yes men, and his ability to listen to and absorb such a range of viewpoints...[contributed] to the complexity of his films,” wrote McBride.

Capra’s choice of leads – his favorites were Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Barbara Stanwyck – is also indicative of his shrewdness. “Each of them brought to a role almost the opposite of the ‘star quality,’” wrote Carney. “They represent a vacancy, blankness, or indefiniteness that...is exactly right for Capra’s investigations of the achievement of identity....They are figures of desire or inarticulate idealism searching for a cause to follow, a leader to embrace, or a satisfactory form of personal expression...”

From 1930 to 1939, Capra seemed to be able to do no wrong: he had few failures and won three Academy Awards as best director. But during the war (when he was the producer of the acclaimed Why We Fight propaganda movie series), he seemed to lose his way. Some say the regimentation of the army dampened his enthusiasm, others argue it was the brutality and suffering he saw in the newsreel footage he gathered for Why We Fight. Whatever the reason, the Capra who returned from the war was a changed man.

His first post-war movie was It’s a Wonderful Life. Although now hailed as a Christmas classic, the film received mixed reviews on release and was a commercial failure. Capra himself worked on the screenplay, the story about a frustrated man who wishes he had never been born. A darkly moving parable about survival, it is brims with anger and pessimism, which some have argued was what Capra himself was feeling at the time.

“It’s a Wonderful Life is a film of endless frustrations, deferrals of gratification, and of the complete impossibility of representing the most passionate impulses and imaginations of the self in the world – and yet the title is still entirely unironic,” observed Carney. Bailey’s life is wonderful because “he has seen and suffered more, and more deeply and wonderfully, than any other character in the film.”

After that, the spark was gone. Ironically, the conservative Capra was pursued by the federal government as a possible Communist and secretly named names. The man whose characters championed lofty principles and “lost causes” himself caved in and was never the same again. In the 1950s, he was reduced to remaking his past classics, filming Broadway plays, and creating TV shows for children. By the 1960s he had retired, although in 1972 he offered his last work of fiction: an “autobiography” that was self-aggrandizing, apparently largely untrue – and a big hit. It made the man a star all over again.

By the time he died in 1991, many critics were still divided on whether Frank Capra was a great filmmaker or just a great fraud. But one thing everyone did agree on was that the director’s best movies had helped define his country. “Maybe there really wasn’t an America,” filmmaker John Cassavetes once observed. “Maybe it was only Frank Capra.”