You are hereMagazines 2000-2009 / Planet of the Apes

Planet of the Apes

REVISITED By TOM SOTER from DIVERSION, 2000

REVISITED By TOM SOTER from DIVERSION, 2000

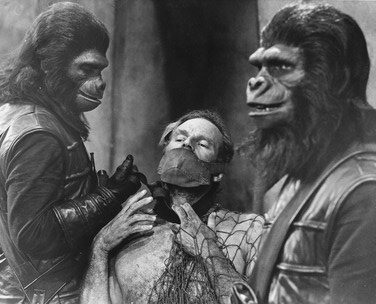

Get your hands off me: Charlton Heston and apes.

The three American astronauts, marooned on an unknown planet and led by Colonel George Taylor (Charlton Heston), have just stumbled onto their first sign of human life: a collection of near-naked people swinging from trees and eating fruit. “We got off at the wrong stop,” moans one of the three. “You’re supposed to be the optimist, Landon,” says Taylor. “Look on the bright side: if this is the best they’ve got around here, in six months, we’ll be running this planet.” Suddenly, a strange, trumpet-like sound is heard. The humans all freeze in apparent fear. Then, as the music on the movie’s soundtrack begins pounding out a relentless beat, everyone begins running towards the underbrush. Gunshots are fired. Humans fall. Horses come thundering by and the camera follows them, zooming in on one rider as he turns to face us. As the trumpets blare, he is revealed to be a fully clothed ape.

This striking scene – one of the most singular moments in film – is, of course, from Planet of the Apes, the first and best of what would eventually become a series of five movies, two TV shows (one live, one cartoon), countless books and comics, and even a number of web sites. Although it has been 30 years since Charlton Heston went ape, the film’s influence and popularity are still widely felt throughout the world. Eric Greene’s recent book, Planet of the Apes as American Myth, analyzes the racial themes of the movie. Dialogue from the film has become fodder for comedians (“Get your stinking paws off me you damn, dirty ape” has been used as a punchline for one too many jokes). A restored version of the movie’s Academy Award-nominated soundtrack has been released on CD. And the movie’s message and imagery have been employed by politicians and peaceniks alike to discuss everything from racism and gun control to environmentalism. “This isn’t the Planet of the Apes,” former New Jersey Governor Jim Florio told gun advocate Charlton Heston in 1990. “This is New Jersey.” Not surprisingly, Planet of the Apes may be coming back. Plans are underway for a big-screen remake/sequel starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Produced by Oliver Stone, the movie purportedly focuses on a geneticist who travels back in time to save the human race from warmongering apes. Co-producer Jane Hamsher has said that the movie will have “Oliver's stamp and political take on it.”

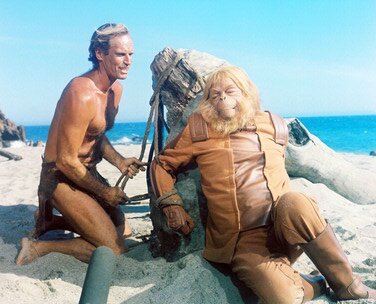

A madhouse: Charlton Heston and Maurice Evans.

Yet it almost never was. The original novel was penned in 1963 by Pierre Boulle, a popular French writer best known for The Bridge on the River Kwai. Boulle’s story, set in earth’s future, follows the adventures of Ulysse Merou as he lands on a planet dominated by intelligent apes. He got the idea from a visit to the zoo where he watched the gorillas. “I was impressed by their human-like expressions,” he told Cinefantastique magazine in 1972. “It led me to dwell upon and imagine relationships between humans and apes.” A straightforward, philosophical tract, the novel uses ape culture to skewer human foibles. His twist ending: Merou returns to earth, only to find that, it, too, has been overrun by intelligent apes.

A number of producers thought the story had cinematic potential, although Boulle himself was skeptical. “I never thought it could be made into a film,” he said in Cinefantastique. “It seemed to me too difficult, and there was the chance that it would appear ridiculous.” One company wanted to shoot it as low-budget drive-in movie with actors wearing rubber masks, but Arthur P. Jacobs had other ideas. The producer hired “Twilight Zone” creator Rod Serling to draft a screenplay (he eventually wrote 40 versions) and then spent nearly two years shopping it around to different studios. No one was interested. Jacobs eventually convinced 20th Century Fox – which produced Stars Wars in 1977 – to spend millions developing ape make-up and to shoot a five-minute test scene. “Everyone thought that no one would believe an ape talking to a man,” Jacobs told Cinefantastique, “and I said, ‘I will prove to you that they will believe it.’ We packed the screening room...and [Fox president Darryl] Zanuck said, ‘If they start laughing, forget it.’ Nobody laughed. They sat there, tense, and he said, ‘Make the picture.’”

Before shooting began, Michael Wilson, an Academy Award-winning writer who had been blacklisted during the Communist “witch” hunts of the 1950s, completely rewrote the script. In his version, Merou became Taylor, who could have been a stand-in for the politically conscious Wilson: cynical, acerbic, and disgusted by American hypocrisy. He has left earth to find something better than man. The irony is that he discovers something infinitely worse. Like Boulle’s original, Apes mocks humanity. “I had never thought of this picture in terms of being science fiction,” director Franklin Schaffner told Cinefantastique. “More or less, it was a political film, with a certain amount of Swiftian satire...it must occur to you as you are watching an ape society, you are looking into a mirror...” Unlike the novel, however, the film combines fast-paced action with unusual characters to create an entertainment that is both exciting and thought-provoking.

You might not like what you find: Evans and Heston.

Shot on location in Arizona and Utah as well as on Hollywood soundstages, Planet of the Apes was arduous going. The actors who played apes wore special latex make-up (which won an Academy Award) that took 3 1/2 hours to apply. “Our food was always brought to us on the stage,” Kim Hunter, who played an ape doctor, told the New York Times in 1971. “I don’t think they wanted us in the commissary. It would have killed everybody else’s appetite. And you had to eat looking into a mirror in order to see where your own mouth was; it was a good inch or more behind the mouth of the make-up appliance. I gave up. I just couldn’t struggle with solid foods. Instead, I drank lunch through a straw.”

As for Heston, who was nearly naked during most of the movie, the role of Taylor was difficult. “It occurs to me,” he wrote in his diary, “that there’s hardly been a scene in this bloody film in which I've not been dragged, choked, netted, chased, doused, whipped, poked, shot, gagged, stoned, leaped on, or generally mistreated.” He offers a superb portrait nonetheless: biting and nasty yet still heroic. “The picture is an enormous, many-layered black joke on the hero and the audience,” observed Pauline Kael in The New Yorker magazine in 1968, “and part of the joke is the use of Charlton Heston as the hero. I don’t think the movie could have been so forceful or so funny with anyone else. Physically, Heston, with his perfect, lean-hipped, powerful body, is a god-like hero; built for strength, he’s an archetype of what makes Americans win...he’s so magnetically strong; he represents American power – the physical attraction and admiration one feels toward the beauty of strength as well as the moral revulsion one feels toward the ugliness of violence. And he has the profile of an eagle...He is the perfect American Adam to work off some American guilt feelings or self-hatred...”

The movie also presents one of the most memorable concluding images in modern films. Taylor, having escaped the apes, is riding off into the sunset with his lady love along a beachfront. Suddenly, he stops and looks towards something out of camera range. He goes from stunned amazement to shock, and finally to a bitter tirade against mankind. “God damn you all to hell,” he says, sinking to his knees and beating the sand. “You blew it up.” Then we see what he has seen: the buried, broken remains of the Statue of Liberty. Through a time warp, he has come back to earth. The dark, surprise ending is a big part of the movie’s enduring attraction, both shocking and disturbing, a dire warning about where humanity’s follies could lead. The adventure-with-a-message formula paid off at the box office, too: the series took in an amazing $82 million in the U.S. and changed the way society viewed science fiction.

Previously considered kid stuff with no profit potential or critical merit, the Apes movies foreshadowed the even-greater success of Star Wars and The Terminator movies. But unlike those action epics, the Apes adventures offered sci-fi with a satirical sting, using the genre to make points about war, racism, and peaceful co-existence. Indeed: released at a time of great social unrest – campus protests and anti-Vietnam War violence were on the rise – the movies’ tapped into the growing fears of audiences, concerns which resonate to this day. And if Planet of the Apes had a grim conclusion, its four sequels dealt with anti-war and race issues even more darkly, as apes and humans become caught up in an increasing cycle of violence and hatred. Pessimistic? Sure, but the movies ultimately succeeded because they cleverly used science fiction to disguise themselves as engaging, out-of-this-world adventure epics. Apes ruling the world? Gee, what’ll they think of next? As Rod Serling observed in 1972: “It’s a walloping science fiction idea.”

REVIEW FROM VIDEO MAGAZINE

PLANET OF THE APES Color. 1967. Charlton Heston, Roddy McDowell, Maurice Evans, Kim Hunter; dir. Franklin]. Schaffner. 112 min. Beta, VHS. $59.98. Playhouse. Reproduction: A ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET OF THE APES Color. 1971. Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, Bradford Dillman; dir. Don Taylor. 97 min. Beta, VHS. $59.98. Playhouse. Reproduction: A

Planet of the Apes is a terrific movie with a bad reputation. That can be blamed more on its progeny-four sequels and a shortlived TV series-than on any flaws of its own. For Planet is not just men in monkey suits. It is a grand adventure that is as witty as it is wonderful. It even has a point to make about our times.

[[wysiwyg_imageupload:1240:]]

Charlton Heston, that icon of religious films, is perfectly cast as the 20th-century cynic stranded in a future world gone ape. With his streamlined physique, he is the "perfect man" a la Michelangelo, constantly moving to avoid the crouching apes, who want to lobotomize, castrate, or kill him. As Taylor, a bitter loner who left earth "in search of something better than man," Heston only finds creatures who are infinitely worse, and the movie is one lesson after another in his humility-and mankind's.

Planet of the Apes is the kind of parable you'd expect to find on The Twilight Zone, and it's no surprise that Rod Serling coauthored the tale. His cerebral script (written with Michael Wilson and based on Pierre Boulle's Monkey Planet) has been given passion and energy by Franklin J. Schaffner, a director who stages action scenes remarkably well. Besides the dramatic first appearance of the apes, he gives incredible pacing and poetry to Taylor's attempted escape-from Ape City. He also has an eye for colorful panorama (including a beautifully moody trek through the arid Forbidden Zone) and coaxes engaging performances from Roddy McDowell, Kim Hunter, and Maurice Evans as two chimpanzees and an orangutan. To cap it all, Jerry Goldsmith provides a haunting score, one of the best ever done for film.

Unfortunately, if Planet is a classy Twilight Zone, the rest of the series is closer to Lost in Space-although the middle movie, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, gets some mileage out of inverting the original film's premise. Two talking apes arrive in Los Angeles, 1973. 'they are wined and dined at first but ultimately persecuted by , all sorts of nasty humans, showing that we are no better than the apes in the first movie. McDowell and Hunter are warm and winning as the chimpanzee couple, the Paul Dehn script verges on clever, Goldsmith turns in a fun paro¢y of his original score, and the opening sequence is improbable but funny.

The other entries, however, do little beyond continuing to wow viewers with John Chambers' Oscar-winning ape makeup (which took five hours to put on and three to take off). Beneath the Planet of the Apes, the second, is aptly named: a tepid rehash of Planet, with mutants, militant gorillas, and some snazzy special effects tossed in to overcome the paucity of fresh ideas. The last two installments, Conquest of and Battle for the Planet of the Apes, are the sort of films that have given the series a bad name: illogical and mindlessly action-oriented, aimed at undemanding kids weaned on TV adventure shows of the lowest order. Man might have evolved from apes, but it's hard to believe that these came from Planet.

As for transfer quality, Playhouse has done a good job, with fine color. The first film is the only one designed for the wide screen and therefore suffers the most (although the minimal panning and scanning is relatively unobtrusive). Planet's brilliantly evocative score is crisp and clear, however, especially in VHS Hi-Fi. 1986