You are hereMagazines 1990-1999 / Television Shows / The Saint

The Saint

![]()

THE SAINT

By TOM SOTER

from DIVERSION, 1996

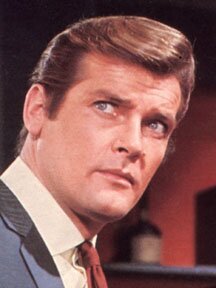

The Saint is a sinner. But The Saint is also a winner. Roger Moore as The Saint, with friends.

Roger Moore as The Saint, with friends.

“Need I explain that you have come to the end of your interesting and adventurous life?” sneers the villain to Simon Templar, a.k.a. The Saint.

Simon twitches an eyebrow, and slides his mouth mockingly sideways. “What – not again?” he sighs.

The villain looks puzzled. “I don’t understand.”

“You haven’t seen so many of these situations through as I have, old horse. I’ve lost count of the number of times that this sort of thing has happened to me. I know the tradition demands it but I think they might give us a rest sometimes. What’s the program this time – do you sew me up in the bath and light the geyser, or am I run through the mangle and buried under the billiard table? Or can you think of something really original?”

The scene is from the book The Saint vs Scotland Yard (1931) and the hero in peril is Simon Templar, the man with the crooked halo who forever transformed the way audiences look at heroes and villains. Self-mocking, suave, with his own moral code, Templar, like his spiritual descendant James Bond, is among the first of the flamboyant fictional anti-heroes who could nonchalantly walk into a scene, comment on its absurdity, and then steal it outright. Indeed, before The Saint, fiction’s stalwarts were upright, law-abiding, and eminently predictable, more interested in good works than wine, women, and wealth. But since his first appearance in Meet the Tiger in 1928, The Saint has changed all that.

Templar begat James Bond and a whole line of the cinema’s smart-aleck, vigilante protagonists. When Bruce Willis’s cinematic tough guys mock no-nothing, pompous authority figures, he is echoing what The Saint first did in print over 60 years ago. And The Saint is still a phenomenon in his own right. Since 1928, the 64 Saint books have sold over 40 million copies, while the character has appeared in some 14 films (the first in 1938), two TV series (the most famous starring Roger Moore), six TV-movies, a number of radio series, comic strips, bubblegum cards, his own magazine, and now, in what could be the grandest incarnation ever, a $60 million Paramount picture slated for winter, starring Val Kilmer and Oscar nominee Elizabeth Shue. The new movie, says an insider, will present a “Simon Templar for the ‘90s. He is still a playboy but The Saint has been brought right up to date.”

No one would have predicted such a long, prosperous life for the British buccaneer. When he first appeared, the character was simply one of many created in the roaring ‘20s by a 20-year-old Cambridge student named Leslie Charteris (born Leslie Charles Bowyer Yin in Singapore). The young author was fascinated by the flamboyant. He had taken his pen (and later legal) name from Colonel Francis Charter, a notorious gambler and founder of the Hellfire Club. As a youth, he loved pirate stories and began writing thrillers because he felt he could create better fare than what he was reading. Charteris had his own set of adventures to draw from, as well: he had prospected for gold in the jungle, fished for pearls, labored in a tin mine, and worked as a bartender in a country inn – all in the name of adventure.

The Saint, created in a period when fictional “Gentlemen Outlaws” had colorful nicknames like The Toff, The Baron, Nighthawk, and Blackshirt, followed in the Robin Hood tradition: a well-bred, well-dressed hero helping the underdog against a muddled establishment. The Saint, often dubbed “The Robin Hood of Modern Crime,” was an iconoclastic adventurer, whose credo, as expressed in the short story, “The Melancholy Journey of Mr. Teal,” was straightforward: “To go rocketing around the world, doing everything that’s utterly and gloriously mad – swaggering, swashbuckling, singing – showing all those dreary old dogs what can be done with life – not giving a damn for anyone – robbing the rich, helping the poor – plaguing the pompous, killing dragons, pulling policemen’s legs...” The first Saint.

The first Saint.

The Saint stories are fast-paced, intricately plotted, and highly unpredictable, dealing with stolen jewels, unexplained murders, and hair’s breadth escapes. And they are all done in a tongue-in-cheek style that readers of the ‘30s found uniquely brash (a typical Saintly rejoinder: “I hate to disappoint you – as the actress said to the bishop – but I really can’t oblige you now”).

The plots swung from action-packed boy’s adventures to murder mysteries to psychological studies, all written with a distinctive, nonchalant air. In Getaway, for instance, Templar intervenes in a sidewalk beating and is soon swept away in a rollicking saga involving multiple murders, torture, and jewel theft, as our hero dangles from speeding cars, moving trains, and castle windows. “The Story of a Dead Man,” an early short story, finds Templar masquerading as a member of a notorious gang in a multi-layered mystery that keeps the reader guessing right up until the climax, when the Saint is trapped in a gas-filled dungeon. “The Unfortunate Financier,” another short story, shows The Saint playing mind games with a con man who is too clever for his own good.

“When I start to plan a story,” explained Charteris in the 1960s, “the tests which they must meet to satisfy me, are (1) Is the story line conventional? If so, then how can it be twisted to outrage convention? (2) Is this character someone I can see and feel as flesh and blood, or is it a cardboard cut-out that I saw on some screen? If so, what does it need to make it different? I have always wanted to be an originator: let the others imitate me.”

Readers loved Simon Templar’s brand of insouciant adventure, and seven Saint books appeared within two years. “...the public of the grey, depression-cowed early thirties needed The Saint so badly that nothing would have induced them not to believe in him,” observed William Vivian Butler in The Durable Desperadoes. “Or to surrender that all-important illusion that maybe with the help of the right tailor, maybe by continually polishing up their drawling repartee, they might, if only for a moment or two, bring themselves to resemble him.”

“The Saint is a compromise,” Charteris once explained. “He can have all the fun and sympathy of the fugitive from justice, while at the same time his motives are most impeccably commendable. He can be rude to policemen and at the same time do their work for them.”

George Sanders as the Saint.Not surprisingly, Hollywood soon came calling. Louis Hayward was the first cinematic Saint in The Saint in New York (1938), based on a Charteris novel that depicts Templar as a paid avenger, assassinating a series of criminals the law cannot touch.The character’s dark side was considerably softened in subsequent motion pictures (the most well-known of which starred George Sanders) and radio series (one of which featured Vincent Price, who played The Saint as a gourmet whose greatest peeve was being interrupted while dining).

George Sanders as the Saint.Not surprisingly, Hollywood soon came calling. Louis Hayward was the first cinematic Saint in The Saint in New York (1938), based on a Charteris novel that depicts Templar as a paid avenger, assassinating a series of criminals the law cannot touch.The character’s dark side was considerably softened in subsequent motion pictures (the most well-known of which starred George Sanders) and radio series (one of which featured Vincent Price, who played The Saint as a gourmet whose greatest peeve was being interrupted while dining).

By 1962, when The Saint reached television in the person of Roger Moore, he had become more of an amateur detective/playboy than vigilante, traveling the world in search of adventure, tossing off ironical asides as he assisted those in need. In “The Loaded Tourist,” he becomes involved in an Italian jewel swindle/murder plot when he helps a 16-year-old Italian boy search for the murderer of his father. “The Talented Husband” finds him in England trying to outsmart a serial wife-killer. “The Careful Terrorist” brings him to America, as he continues a murdered friend’s campaign against a corrupt union boss. This Templar is recognizably Charteris’, however, with a taste for fine food and good clothes, and a regular nemesis in Chief Inspector Claude Teal of Scotland Yard.

“The stories always have a very good twist,” Moore said in 1966. “The Saint stories have never had the sex of Mickey Spillane or the brutality of James Bond.”

The new Saint movie has been in the planning stages since 1991, and follows a 1978 TV series starring Ian Olgivy, and six 1989 TV-movies with Simon Dutton. It reportedly attempts to make Templar a hero for the ‘90s by returning him partly to his more shadowy 1930s roots. According to a report in Screen International, “Director Phillip Noyce has looked for inspiration to Leslie Charteris' original stories rather than the 1960s TV series...making the character of Simon Templar...much darker than in his small-screen incarnations. ‘I want to portray how a sinner becomes a saint and how someone is redeemed,’ Noyce explains.”

“The character of The Saint is very much the same as he always was,” one of the movie’s producers,William MacDonald, told Burl Barer in The Saint: A Complete History, “although we must say that probably in the interest of establishing exactly why a Saint in the ‘90s becomes a Saint, we are going to create a little more of a back story than was originally related in the books...[but] the classic Saint characterization found in the books should be fully incorporated into the screenplay.”

The Saint features Val Kilmer as Templar, about whom Roger Moore noted recently, “I think he will draw a big audience and make it very successful. As my company is involved in it, I'm very, very happy about it.” Kilmer, whose salary for the movie is in the $6 million range, has played unconventional heroes before: rock singer Jim Morrison in The Doors, an unconventional psychologist in the film noir tale Dead Girl, and the caped crusader in Batman Forever. Leaving Las Vegas Oscar nominee Elizabeth Shue co-stars as Dr. Emma Russell, a young electrochemist who falls in love with The Saint. Lensed in Moscow’s Red Square and the Kremlin, as well as in Toronto and locations throughout England, the movie has undergone a number of rewrites (there have reportedly been five different screenwriters) before satisfying the producers and Charteris, who died in 1993 at age 85. (An early script featured Moore as The Saint’s father, but subsequent plans for a cameo didn't work out; the actor’s son Christian is a video assistant on the shoot, however.)

“A third script has now been started by a new writer who has actually read some Saint books,” wrote Charteris in 1992. “This is, of course, an unprecedented innovation by Hollywood standards.” The finished Saint movie, however, looks to be inspired as much by 007’s cinematic exploits as by Charteris, dealing with cold water fusion and featuring Russian troops and tanks, explosions, and fleeing gypsies on the Moscow subways. Nonetheless, one writer on the film noted to Barer, “I am...connecting as much as possible with the Saint myth and using Charteris’ original dialogue whenever I can.”

Whether the filmmakers succeed in capturing the true Saint or not, one thing is certain: Simon Templar himself will survive, as he always has, with his halo – if not his virtue – intact. “I don’t see why he shouldn’t go on another 30 years,” said Charteris shortly before his death. “He is the last of the fictional swashbucklers in the tradition of Dumas...the last guy who could fight with a laugh and a flourish and a sense of poetry thrown in.”

SAINT SIDEBAR

Roger Moore as The Saint.

Roger Moore as The Saint.

The Saint is coming to the big screen and that has created activity on other fronts. Among the current Saint-related items:

Columbia House Video will release the first volume of The Saint: The Collector’s Edition on October 28, 1996. The collection is available through mail order only. The initial tape, featuring “The Talented Husband,” the premiere black and white TV episode from 1962, and “The Death Game,” a much-later color installment, is priced at $4.95 (plus shipping and handling); subsequent volumes (nine more are scheduled) will cost $19.95 each, plus shipping and handling. Each edition will be sent every four to six weeks.

RKO is remaking the classic Saint films of the 1940s for the USA cable TV network. The first will be The Saint in New York,. The search for a leading man is underway.

Pocket Books has contracted with Edgar Award-winning author Burl Barer to write The Saint, a novel based on the Wesley Strick screenplay of the new Val Kilmer adventure.